Coast Salish

Denis Finnin/AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/874

Selected features from the Northwest Coast Hall.

Coast Salish people are a diverse group of more than 40 independent Nations. We speak more than 20 languages and dialects that are related, but distinct. Coast Salish territories lie on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border, in coastal British Columbia and Washington State.

The term Coast Salish was coined by linguists to refer to our languages, which are related. More than 20 distinct languages and dialects belong to the Coast Salish language family.

WELCOME TO THE NATION: COAST SALISH

[secəlenəχʷ | Morgan Guerin speaks to the camera.]

secəlenəχʷ | MORGAN GUERIN (Musqueam, Consulting Curator): [speaks hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓] Dear friends and relatives, [speaks hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓] my name is Morgan Guerin. My ancestral name is secəlenəχʷ.

I'm very happy to be here to say a few words of welcome, on behalf of the Coast Salish people.

[Chief Ian Campbell, wearing a headdress and a button-down shirt, speaks to the camera.]

CHIEF IAN CAMPBELL: [speaks hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓] Welcome. [speaks hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓]

[secəlenəχʷ | Morgan Guerin speaks to the camera.]

secəlenəχʷ | MORGAN GUERIN: [speaks hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓] You are welcome.

Cities Through Time

Two major cities—Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia—were built on Coast Salish lands. Before the Vancouver area was colonized, a Musqueam village and trading center called c̓əsnaʔəm flourished there for more than 4,000 years. In both cities, many people from Coast Salish Nations continue to live near their ancestral homes.

The History of Seattle

The city of Seattle takes its name from Chief siʔaɫ, a Duwamish and Suquamish leader.

Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI)

Eric Willhite

Braunger-Ullstein Bild/The Granger Collection, New York

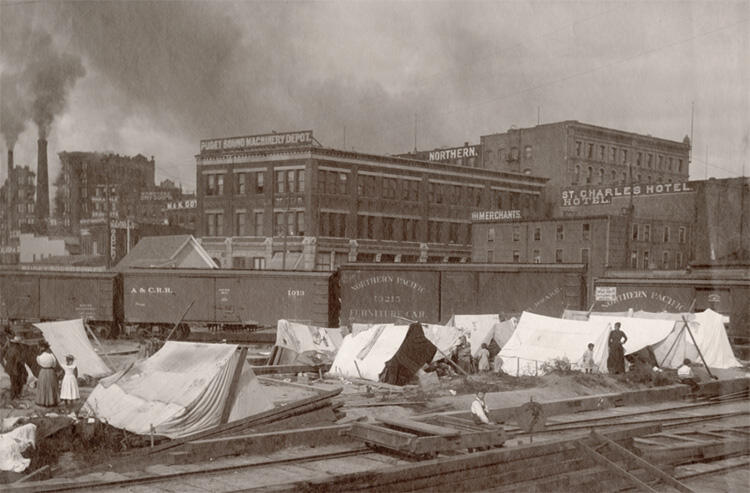

Duwamish and other Coast Salish people, the original inhabitants of the Seattle area, were forced out by Euro-American settlement in the 1800s. But they continued to come to Seattle by canoe, bringing shellfish, baskets, and other items to sell in city markets. Because they were not allowed to camp or stay within the city limits, they moored their canoes and pitched tents on Ballast Island, which had formed in the harbor from rubble dumped from ships and other landfill.

Ballast Island at the foot of Washington Street, Seattle, Washington, around 1891.

Ballast Island at the foot of Washington Street, Seattle, Washington, around 1891.University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections NA680

In this photo taken around 1891, a plank road connected Ballast Island to Railroad Avenue (today called Alaskan Way).

In this photo taken around 1891, a plank road connected Ballast Island to Railroad Avenue (today called Alaskan Way).Museum of History & Industry, Anders B. Wilse Collection, 1990.45.14

In Coast Salish Territory—Vancouver

The xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam) people have lived in what is currently called Vancouver for thousands of years.

Some of our sχwəy̓em̓ (ancient histories) describe the landscape as it was over eight thousand years ago.

—Musqueam Indian Band

George Lawson

George Lawson

Museum of Anthropology at UBC, Vancouver, Canada

Coast Salish Baskets

The skilled weavers who designed and created the beautiful baskets in the Northwest Coast Hall came from nine different Nations within our larger cultural community of Coast Salish people. The varied textures and patterns reflect the diversity of our people and our homelands in southwestern British Columbia and western Washington State. Our weavers developed a range of styles for different uses, such as hauling shellfish, picking berries, carrying water, storing clothing, serving guests and keeping a baby secure and warm.

Sharron Nelson, a Chinook and Puyallup basket maker from Tacoma, Washington, in 2011.

Sharron Nelson, a Chinook and Puyallup basket maker from Tacoma, Washington, in 2011.Center for Washington Cultural Traditions

Suquamish master weaver Ed Carriere runs nettles through a wringer to make twine for sewing tule mats.

Suquamish master weaver Ed Carriere runs nettles through a wringer to make twine for sewing tule mats.Erin Chapman/© AMNH

ťqaỷas | Seal Roost Basket

Click on the 3D model below for a closer look.

This striking pattern, called “seal roost,” was first developed by Twana basket maker kayasic’a, also known as Betsy Adams, in the 1800s. Later, each weaver varied the design to make it her own. The concentric rectangles represent rocks, while the small triangles overlapping them indicate resting seals. Wolves travel around the rim counter-clockwise, the direction that people dance in Coast Salish ceremonies.

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/8848

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/8876

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/4899

AMNH Anthropology catalog 50/2505

Basket making is an exacting art. By creating elegant baskets like those displayed in the Hall, women—and sometimes men—could win acclaim for themselves and their families. Richly patterned coiled baskets are especially prized. In the 1800s, our weavers created them in quantity, to be widely traded or given away at feasts. In some communities, baskets received as gifts were carefully stored and kept pristine. After the owner died, relatives held a memorial ceremony, and the baskets were distributed to guests.

My mom used to gather us kids and grandkids together every Sunday for basket-weaving classes and family dinner. Our family continues this tradition, meeting at the family home and weaving on Sundays throughout the winter months. Summer months are spent gathering and drying the basket materials.

—Tsl-stah-ble | Trudy Marcellay, Basket maker

Chehalis and Nisqually, Washington State

Artist Profile: Ed Carriere

Northwest Coast Basketry—Woven Traditions

[AMBIENT FOREST SOUNDS AND BIRD CALLS]

[Short video clips cycle showing Ed Carriere picking up a branch from the forest floor surrounded by cedar trees, using a knife to peel some bark from a cedar limb, digging amongst tall grasses.]

ED CARRIERE (Suquamish Elder and Master Basket Weaver) [Voice Over]: I come from the Suquamish reservation. Suquamish Washington. A little town of Indianola.

[A black-and-white of Julia Jacobs, Ed Carriere’s great grandmother, appears.]

CARRIERE: My great grandma, she was the one that wove these really beautiful clam baskets for the tribal clam diggers.

[Ed harvests tall grasses, pulls strips of inner bark from a fallen cherry tree, uses a knife to peel away layers of bark, and folds up a thin strip of cherry bark.]

CARRIERE: And so I would watch her when I was little. When I got about 14 years old, I got brave enough to make my own clam basket. That led me into basket weaving.

[Ed cuts down tule plants from a marshy area and demonstrates separating the layers of the stalk.]

CARRIERE: It’s really satisfying to go out and, oh, cut tulles or cattails or go out and pick sweet grass.

[Back in Ed’s home, Ed prepares nettle fibers for making rope and splits a cedar limb.]

CARRIERE: If I collect it, I got to make something out of it, you know? I can’t just let it sit there, because it’s sitting there saying, hey, use me, use me. Make something out of me.

[ED LAUGHS]

[MUSIC FADES UP]

[The American Museum of Natural History logo appears, followed by the title: Woven Traditions: Northwest Coast Basketry]

[A series of shelves in the Museum’s Anthropology collection are slid open, revealing many woven Northwest Coast baskets of different shapes and patterns.]

AMY TJIONG (Associate Conservator, Division of Anthropology): We have a lot of baskets in our collection.

[More shelves of Northwest Coast woven basketry reflect the diversity of materials and techniques used to create them.]

TJIONG: The plant materials themselves in these baskets, over time, they dry out, they become embrittled, and sometimes when we have to treat objects, it can get complicated.

[The Museum’s Northwest Coast Hall circa 2018 is shown with the caption “Northwest Coast Hall Before Renovation”]

TJIONG: The Northwest Coast Hall is over 100 years old…

[The hall is now shown in the midst of construction with empty cases and scaffolding, with the caption “Northwest Coast Hall During Renovation”]

TJIONG: …and I’m part of the team that is updating, restoring, and conserving the hall.

[Amy Tjiong sits in front of shelves of Northwest Coast basketry in the Museum’s Anthropology collection]

TJIONG: The conservation team has been tasked with conserving 800-plus objects.

[Museum conservators clean and conserve a variety of Northwest Coast collection pieces.]

TJIONG: That involves making sure that the objects are stable for display. It's really important to us to get input and guidance from the community members.

[A conservator uses a special vacuum hose and a brush to remove dust from Northwest Coast baskets.]

TJIONG: We were hoping to find somebody who would be able to tell us more about the materials that we see in these baskets and the technologies. We had reached out to our core advisors and Northwest Coast basketry scholars. Everybody said that we should reach out to Ed.

[Ed Carriere sits at a table laid out with his basketry and basket-making materials and tools in the Museum’s Division of Anthropology. He holds a large woven basket.]

CARRIERE: This clam basket…my specialty. What got me started in weaving.

[Photograph of Ed Carriere with staff members from the Division of Anthropology]

TJIONG: We invited Ed to visit the conservation lab…

[Photograph of Ed holding a cedar tree limb while giving a presentation to Museum staff.]

TJIONG: …for a working visit in 2018.

[Short clips cycle through of Ed holding and describing the variety of baskets and basket-making materials he brought to the Museum.]

TJIONG: He brought, I mean suitcases full of plant materials that he had harvested, and baskets that he had woven.

[Camera pans across four intricately woven Coast Salish baskets with distinct shapes and designs.]

TJIONG: And at the same time, he would have the opportunity to view objects from his area, the Coast Salish region, within the collection.

[Curator Peter Whiteley sits in front of a Northwest Coast house screen with baskets next to him in the Museum’s Division of Anthropology.]

PETER WHITELEY (Curator, Division of Anthropology): We have a great variety of baskets from people all up and down the coast.

[As he names each nation, an example of a basket from that culture appears on screen.]

WHITELEY: Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, from everywhere.

[A map of the Northwest Coast appears onscreen, color-coded to show the territories of the Native nations of that region.]

WHITELEY: But Coast Salish are distinctive.

[The map zooms in on the Coast Salish territory, which remains colorful while the rest of the map fades.]

WHITELEY: The symmetry of the designs, the complexity of the weaves, that's something that Coast Salish is especially known for.

[The camera slowly zooms in on several Coast Salish baskets, showing their intricacy.]

WHITELEY: Basketry, wooden boxes, those were people's containers.

[A Northwest Coast basket rotates in a circle, showing it to us from all angles.

WHITELEY: People in this part of the world didn't make pottery like they do in the native Southwest.

[Examples of Northwest Coast basketry from the Museum’s Anthropology collection.]

WHITELEY: And there are many different types of baskets for different purposes and with a very sophisticated technological knowledge that goes into them.

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: So there’s the clam basket.

[A large rectangular basket with a single handle on the top, with spaces between the warps and wefts.]

CARRIERE: And then the burden basket.

[A more tightly-woven basket with small handles on the sides and a rope around it that would have been used to put across one’s forehead while carrying it.]

CARRIERE: And then there’s the folded bark basket.

[A cylindrical-shaped basket visibly made from a large sheet of bark that has been folded at the bottom.]

CARRIERE: Then there was the hard-coiled cooking basket.

[Several examples of large, very tightly-woven baskets.]

CARRIERE: The weave is so tight that it forms a solid wood vessel, and so it would hold water, and then they could put foods in it and hang hot rocks in there and boil foods quickly in that type of a basket. Which I thought was incredible.

[LAUGHS]

[Photograph of Ed’s Great Grandmother, Julia Jacobs, with several baskets she wove.]

CARRIERE: It was my goal to weave like my ancestors did.

[A series of photographs shows Ed examining baskets and woven pieces in the Museum’s collection, and talking to conservators about basket-weaving materials.]

CARRIERE: So I fulfilled that through archeology and through museums, and seeing these old pieces that are stored away.

TJIONG: But having him bring the harvested materials to the Museum, that's just one piece of a larger story.

[Fade to black.]

[WAVES GENTLY LAPPING]

[Fade up to clear blue water lapping against a rocky beach shore.]

TJIONG: There were many reasons for visiting Ed at his home.

[Leaves gently rustle in a lush forest with thick-trunked trees covered in moss.]

TJIONG: Many of our advisors have told us time and time again how important it was for us to visit the land where they came from.

[Cattails sway in the breeze. Water laps at the beach with dense forested islands in the distance.]

TJIONG: That we will never truly understand until, you know, we've breathed the air, until you know we've seen the landscapes.

[Ed leads Amy through tall grasses and brush.]

TJIONG: He took us he took us along the beach to a sandspit where we were able to harvest these grasses that were taller than us.

[Ed shows Amy some stalks of tule and cattail he just cut.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: They’re a little fragile, but once you get ‘em woven, they’ll make a really pretty little basket.

TJIONG [Voice Over]: Into the forest where you had cherry trees and cedar trees growing.

[Ed shows Amy how he peels outer bark from inner bark on a strip cut from a cedar tree.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: Now, when I make a folded bark basket, I use the whole thing.

TJIONG [Voice Over]: When it comes to the materials, we only see the finished product. Just getting to see these raw materials is helpful so that we're able to identify what we see in the baskets.

[Amy squeezes a freshly cut tule stalk in the sandspit.]

TJIONG [On Camera]: Oh wow, big difference.

[Amy and Ed harvest grasses and tall brush.]

TJIONG: He taught us how to distinguish between, you know, say for example like bear grass and swamp grass. And this isn't something that you would be able to do just by looking at a basket. You would really need to feel the length of the grass.

[Ed demonstrates splitting a cedar limb back at his home.]

TJIONG [Voice Over]: He taught us how to split the cedar limbs into several layers, each one that could be used for weaving.

[Amy splits a cedar limb with Ed’s guidance.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: If it goes to one side, pull to the other side. Just kind of feel it out.

[Ed uses a knife to cut small twigs off of a long cedar branch.]

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: The difference between a basket maker and a basket weaver is a basket maker buys some of his fibers at the store…

[Ed creates nettle rope by crushing nettle plants, breaking them into thin fibers, and braiding them. He holds out the finished product in his hand.]

CARRIER: …but a basket weaver goes out and collects and splits and makes his own warps and wefts and his own fibers to weave the basket with. So there’s a difference there.

[Ed and Amy walk through the forest and harvest materials. Ed demonstrates various techniques of processing basket-making materials.]

TJIONG: Many of our advisors, including Ed, they have such a deep understanding of these materials and the technologies, more so than then we do as conservators. Just because, unless you've grown up with these materials at your doorstep, you know, these traditions are handed down to you through generations. It would only make sense that they've amassed this deep wealth of knowledge.

[Back at the Museum, Anthropology and Exhibitions staff, including Peter Whiteley, arrange baskets in a mock-up of the display that will be installed in the renovated Northwest Coast hall.]

WHITELEY [Voice Over]: As we think about how to display these baskets, we're really dependent upon the advice of our advisors, and they've offered a great deal of new information that we hadn't even been aware of previously.

[Transition from Peter looking at baskets in Museum mock-up display to Ed and Amy looking at Ed’s baskets in his home.]

WHITELEY: It’s essential to collaborate with First Nations communities, and artists, and scholars, and historians. You have to have those perspectives because that's where the knowledge is, that's where the understanding is.

CARRIERE [On Camera]: A basket tells the story of those people.

[Ed twists and braids fibers into rope.]

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: Even when I’m weaving one of those, I can actually feel my ancestors helping. I can feel them helping my fingers and my hands do the right move to weave with. So I really believe in that theory of through basketry we have a direct link to the past, to our ancestors way back.

[Wide shot of a field with Ed and Amy walking together in the distance.]

[Credits roll.]

We’wutth’ul’s | Weaving

Generations of Coast Salish weavers have spun their own yarn using spindles of different sizes and woven the yarn into cloth on wooden frame looms. The finest blankets are of mountain goat wool, often mixed with other fibers for durability, strength, and warmth. Today, as in the past, we wear blankets for spiritual protection when moving from one stage in life to the next.

To work on a Coast Salish loom, a weaver wraps yarn around two cross beams, forming the warp—the vertical fibers. She weaves over and under in a specific pattern to create a subtle design. In the past, weavers often included wool from unraveled blankets in their compositions. The tufts of red on this blanket are bits of manufactured cloth. Musqueam people say a weaver is one who binds things together, as a woman brings two halves together to make a new life.

To work on a Coast Salish loom, a weaver wraps yarn around two cross beams, forming the warp—the vertical fibers. She weaves over and under in a specific pattern to create a subtle design. In the past, weavers often included wool from unraveled blankets in their compositions. The tufts of red on this blanket are bits of manufactured cloth. Musqueam people say a weaver is one who binds things together, as a woman brings two halves together to make a new life.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/9581 A, B, C, D, G

Spindle whorls are often carved with geometric designs or images of powerful beings. As the spinner watches the whirling design, she transforms wool into yarn for blankets, treasures that signify wealth and spiritual purification. This Quw’utsun’ spindle is carved with a thunderbird catching a salmon.

Spindle whorls are often carved with geometric designs or images of powerful beings. As the spinner watches the whirling design, she transforms wool into yarn for blankets, treasures that signify wealth and spiritual purification. This Quw’utsun’ spindle is carved with a thunderbird catching a salmon.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/1865

Land Rights

In 1970 hundreds of indigenous people in Seattle occupied Fort Lawton—a decommissioned U.S. Army base on land that had originally been Coast Salish territory. Ultimately they won 20 acres within what is now Discovery Park, where they built a cultural center.

In 1970 hundreds of indigenous people in Seattle occupied Fort Lawton—a decommissioned U.S. Army base on land that had originally been Coast Salish territory. Ultimately they won 20 acres within what is now Discovery Park, where they built a cultural center. Associated Press

The Daybreak Star Cultural Center opened in Seattle’s Discovery Park in 1977. It provides an urban base for indigenous people from many communities in the Seattle area. The center was built after Native American activists staged a nonviolent occupation of the land in 1970.

The Daybreak Star Cultural Center opened in Seattle’s Discovery Park in 1977. It provides an urban base for indigenous people from many communities in the Seattle area. The center was built after Native American activists staged a nonviolent occupation of the land in 1970. Andrew Morrison

Musqueam Fishing and Fishing Rights

Learn more about the Aboriginal, ancestral, and treaty fishing rights argued for and won by the Musqueam People in the 1990 Sparrow Decision, which is now a part of the Canadian Constitution.

[Beautiful river landscapes, archival images of canoes and people.]

NARRATOR: We have always lived here since the beginning of time. We are the Musqueam— people of the river grass—and we've been here on the Fraser River and throughout Vancouver's inlets for thousands of years.

History has described that every nation of the world that those who were the richest lived at the river deltas. The Roman Empire, likewise with us here in Musqueam.

[TITLE: MUSQUEAM THROUGH TIME]

[Re-creation of Musqueam fisherman spearing a fish.]

NARRATOR: As long as we can remember, there was a rich food supply here at the Fraser’s mouth, and we hunted, trapped, and fished the rivers and oceans, harvesting salmon. We are traditional hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓-speaking people and are descended from the cultural group known as the Coast Salish here in the Pacific Northwest.

While we welcomed peaceful guests to our territory we also kept a lookout for invaders— northern tribes looking for slaves or resources.

[Chief Ernie Campbell speaking in an interview.]

CHIEF ERNIE CAMPBELL (Chief Councillor, Musqueam): When they'd come down they always used to say you gotta- you gotta stay away stay right of the gray wall. That's what they call Point Grey down there, the big gray wall that you have to go- have to go around it if you go up that river. Unless you're coming in peace and bearing gifts you're in for battle. Because there are battlegrounds just down by the Moli, one of our old villages there. They found skulls and arrowheads and all artifacts of the battles that went on there.

[Re-creation of a lookout running back to village.]

UNKNOWN SPEAKER: We had our various warriors at lookout and these individuals would run to the various village sites to inform those heads of families that we had guests coming. And they would inform them whether or not those guests were indeed friend or foe. You were always prepared that they were the enemy approaching.

These runners were our warriors. They were individuals who had to be physically fit because our lives depended upon it.

[Archival images of Simon Fraser and other Europeans and boats.]

NARRATOR: But in 1808, a new kind of visitor arrived—fur trader Simon Fraser was the first to come overland and down our river. Previous experiences with European explorers—Captain Vancouver and Galiano had taught us to be wary of these strangers. So, when Fraser arrived we attacked.

[Map of Musqueam village sites]

NARRATOR: In those days the Musqueam had some 40 village sites spread out across miles of present-day Greater Vancouver. This allowed us to access the resources and protect our territory.

[Musqueam people singing, dancing, and drumming.]

UNKNOWN SPEAKER: And the warriors there from each village site would amass in strategic locations, ready to do battle. And our government structure depended upon it because we could not lose our young and we could not lose our women, who were basically the true historians of our community. They were the ones who were educating our children.

[Archival images and film of blankets and weavers.]

NARRATOR: The power of our leadership was represented in these mountain goat wool blankets and robes unique to the Coast Salish people and the Musqueam have always had their own distinct designs for these spiritual articles of clothing.

[Debbie Sparrow weaving at loom.]

DEBBIE SPARROW (Artist/Weaver): The blanket that the individual would wear would be identifiable to his place in his home, his family, his community. These more complex blankets— the ones that they wore when they traveled and went to meet King George in England—would be the best-dressed. That's what they're wearing them for. It's when we get ready to go somewhere we wear our suits and our best clothes and that's what they did.

[Weaving displayed in a museum.]

NARRATOR: Once a forgotten art weaving was brought back to life by Musqueam women in the early 1980s.

[Archival images of weaving and people wearing blankets.]

[Wendy John speaks in an interview.]

WENDY JOHN (Artist/Community Leader): My grandfather one day said to me, “You want to see some really nice stuff?” And I said, “Sure.” I must have been maybe 10 or 11. He went upstairs and came down with a bag and in the bag he had an old what they call [unknown] blanket and it was made from goat hair and dog hair and it was a weaving like I had never seen before. And that's really where the whole idea of Salish weaving for me came around. The story of who we are is woven into the blankets.

[Archival images and contemporary footage of weavers]

DEBBIE SPARROW: Today we use sheep wool. However, of course, what they were using were mountain goat, but it was also mixed with dog hair, different stinging nettle material, cedar beaten very finely. And it might been the core of what the hair of the mountain goat would wrap around.

[Musqueam people in the forest, harvesting cedar bark]

NARRATOR: Cedar bark weaving has also been making a comeback and today Musqueam people are revisiting the traditional ways of harvesting cedar, including the blessing of the site. Due to the scarcity of cedar in our now-urban territory, today we need to travel at least an hour away to find the bark we need. Here, our people strip the bark in the traditional way—a technique that can be hard to master but ultimately leaves the trees standing.

[People strip long pieces of bark and artisans weave cedar strips together.]

NARRATOR: Once gathered and dried, these cedar strips will be used to make a variety of traditional objects. like baskets, bailers, and mats.

[Archival images of people, buildings, and canoes.]

NARRATOR: Traditions like weaving continued for many years after contact as we continued to trade with the newcomers. But all of that changed with the coming of disease in the mid-1800s, which took an enormous toll on all First Nations. Then, missionaries and the gold rush followed. As resources were extracted all around us, Musqueam people learn to adapt, working as farmers and fishermen while retaining our cultural ways and spiritual teachings.

[Howard Grant speaks in an interview.]

HOWARD GRANT (Cultural Siʔém | Leader) We were fortunate—we didn't have a priest residing in our community because the priests would only come in the summertime. So, when they banned and the potlatch and outlawed it, our people of the past were quite smart. They moved their summer ceremony and merged it along with our winter ceremony, so that they could continue to practice non-stop what they had been practicing for thousands and thousands of years.

[Beautiful and imposing river and ocean landscapes. A woman bathes in a stream, using branches.]

NARRATOR: Beyond our longhouse ceremonies we had a spiritual connection to the land and water around us. The ocean, rivers, and creeks fed us both physically and spiritually. These bathing rituals are important to Musqueam people even today. Combined with sacred dance, song, and ritual in our longhouses we have always found a balance of mind, body, and spirit.

[Archival images of longhouses and people in regalia.]

HOWARD GRANT: We had two kinds of ceremonies—one, the winter ceremony with the longhouse. It was somewhat of a secret society, which only those people who were initiated into it participated and attended. But also, as well, they had potlatches in the summertime whereby another ceremony where our masks were used in the outdoor ceremony to mark the occasion of marriages, namings, memorial, coming-of-age. Within that spiritual rites of passage that allows you to indeed reach to the other senses that the Creator provided to you, that you no longer use. You almost start to see with your ears and hear with your eyes. It's the only way I can sort of describe it.

[Fishing boats ply the Fraser River.]

NARRATOR: Stretching some 1,400 kilometers from its source in northern BC, the Fraser is one of Canada's longest rivers and is the heart and soul of the Musqueam people. While technology has brought a lot of change to our people, we're still tied to this river that has nourished us for centuries. Today, like everywhere in the world, fish stocks are threatened and so these Fisheries officers from Musqueam and Tsawwassen First Nations patrol the Fraser’s waters to ensure that the right salmon stocks are being fished.

This year there's been a huge drop in the number of sockeye on the river and so far, only a brief spring salmon run has been open to fishing. These Musqueam people are continuing a fishing tradition which has run in their families for centuries.

[Trent Sparrow and other haul in nets on a fishing boat.]

TRENT SPARROW (Musqueam Fisherman): Barbecue time! I’ve been fishing this spot for 22 years. Before that was my grandfather and before that was his father. It's done our family well over the, you know, many, many generations since we've been here. And hope to have it for another hundred years to come for my children and my children's children.

NARRATOR: Musqueam has long been on the front lines in getting Aboriginal, ancestral, and treaty fishing rights acknowledged. Thanks to the 1990 Sparrow Decision it is now a part of the Canadian Constitution.

[Large fish are gutted on the deck of a boat.]

WENDY JOHN: When we went to court we said very strongly that our Aboriginal right to fish is something that's been here from time immemorial and we went through all of the the arguments and the Supreme Court of Canada came down on our side of this.

[Wendy John speaks in an interview.]

WENDY JOHN: The Sparrow case set the groundwork for for Aboriginal rights across the country and I think throughout the world because there's been people from throughout the world, Indigenous people coming and asking how they could come to the same place in their communities.

[Wildred Wilson pulling in nets on a fishing boat.]

WILFRED WILSON (Musqueam Fisherman): I have now been fishing on the river here and on the coast of BC for 47 years now. I started with my dad at 8 years of age and every year since. It's not just not just salmon. It's- we’re somewhat in a decline in other stocks here—sturgeon, ooligans. They were a big part of our our diets throughout the year and that's now no more. With any ethnic group in the world that when you have a lifelong and generational connection it becomes a part of you and this river certainly is a part of us. And it always will be.

Reclaiming PKOLS

The Lummi, Nooksack, and other Coast Salish people consider Mount Baker to be sacred. Beyond its natural beauty and ecology, they value it for skalalitude—a sacred state of mind engendered here.

The Lummi, Nooksack, and other Coast Salish people consider Mount Baker to be sacred. Beyond its natural beauty and ecology, they value it for skalalitude—a sacred state of mind engendered here. R. Bishop/AGE Fotostock

On the border of the traditional territories of two Coast Salish groups, the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) and Lekwungen (Songhees), Mount Douglas has long been an important meeting place and a site of an historic treaty signing. Chiefs of the two groups and more than 700 supporters marched on the mountain in 2013 to reclaim its original name, PKOLS.

On the border of the traditional territories of two Coast Salish groups, the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) and Lekwungen (Songhees), Mount Douglas has long been an important meeting place and a site of an historic treaty signing. Chiefs of the two groups and more than 700 supporters marched on the mountain in 2013 to reclaim its original name, PKOLS.Bruce Dean

Spawning Salmon

Kari Neumeyer / The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

All along the Northwest Coast, Indigenous people today continue to celebrate the arrival of spawning salmon. Ceremonies differ from place to place, but in general, people ritually prepare and eat the first salmon caught in the spring. Then, in a formal gesture of gratitude, they return the bones to the water as this family is doing.

Artist Profile: E’ixwe’tiye | Susan Point

Susan Point | E’ixwe’tiye is a master artist and a descendant of the Musqueam people. She is the daughter of Edna Grant and Anthony Point. Susan inherited the values of her culture and traditions of her people from her mother Edna, who learned from her mother, Mary Charlie-Grant.

I continue trying to push myself one step beyond my goals, or one step in a new direction so often. There is always another stride to make. My art is never really finished; there is just a point where I have to stop myself.

—Susan Point | E’ixwe’tiye

Insight. E'ixwe'tiye | Susan Point. Silkscreen print, 1995.

Insight. E'ixwe'tiye | Susan Point. Silkscreen print, 1995.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/2864

This giant carved cedar spindle whorl is a work by Musqueam (Coast Salish) master artist E’ixwe’tiye | Susan Point, installed at the Vancouver International Airport.

This giant carved cedar spindle whorl is a work by Musqueam (Coast Salish) master artist E’ixwe’tiye | Susan Point, installed at the Vancouver International Airport.YVR (Vancouver Airport Authority)

Canoe Journey

The Canoe Journey is an annual, community event that gathers First Nations communities along the Northwest Coast using “the traditional highways of our ancestors.”

In 2019, the Lummi Nation, located in Washington State, hosted the end of the Canoe Journey with the official Canoe Landing and Protocol on July 24. Watch the video to learn more about the significance of the Canoe Journey.

[Archival images of people in canoes and along waterways.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: Since time immemorial we've been a hunting and gathering society and our livelihood was hugely dependent upon the salmon. Up and down the coast, Tribes lived along the waterways where the salmon were on their migratory journey from the ocean, up the rivers to spawn and give new life. The old people knew this, so they prepared themselves to harvest the salmon in the most plentiful places that could be. They traveled by canoe and these canoes provided them with a means to become one with the waters and with the salmon and all living things. And when the newcomers came to this territory that life way had changed dramatically.

[TITLE: CANOE JOURNEY 2019]

[Coastal landscape with houses, cars, and boats.]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: For some people this area is just Washington and Oregon, Canada. And for us it's a mixture of all that. We never had borders. Borders are so háu-us, they're so new. And it brought on and made me think that movie Lion King. Simba's dad is showing him his kingdom, his land, his [unknown]. He was telling Simba that, “Your land is as far as you can see. All the land that Sun touches,” and [unknown]. For us it's more of how far up that sacred path we can paddle. [unknown] It's- we've been here for so long, it's just home.

[Archival images of people, canoes, villages.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: To me the last great canoe journey occurred in 1855 when the tribes went to Mukilteo | bəqɬtiyuʔ to sign the treaty with the newcomers and they gave up the parts of their life way and moved to reservations. This act of assimilation took away a lot of culture of our people. Today it is being reborn through canoe journeys and these things that were once done in our culture, once were relied upon on the waters are being recognized once again.

[A woman in a woven hat speaks near the water.]

WOMAN: There are so many feelings on the water. One, just to get in the canoe with your family in your ancestors’ waters, singing a song that a dear friend made for us when we had no songs, who came from the Lummi Nation—that always takes my breath away. Sometimes when I don't have the strength, I'll just feel the breeze on my back and I feel like that's the ancestors just letting me know to keep going.

[Canoe with name “NaGoodsNooLaxSüüda” painted on the side.]

WOMAN: Her name is NaGoodsNooLaxSüüda. And NaGoodsNoo is “mother's heart.” Süüda is “of the ocean.” So, mother's heart of the ocean.

[People dance and sing inside a large building.]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: [unknown] It's like gathering of our Native people. [unknown] You know, following that sacred path.

[A woman in a woven hat speaks near the water.]

WOMAN: We do travel with many nations. I live in Seattle and I am of the Duwamish Nation and of the Lummi Nation. The colonizers—they told us you were registered one nation, but when you move normally to another nation then they take you in. it's not I'm just Lummi, I'm just Quinault. So, it's it's so important to be out on the water and see what it is like from the water and not from the highway, and to see the eagles above us and to have the youth out there experiencing that. They'll carry this on with their generations.

[People load into canoes. Onlookers stand on the shore.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: As the dates drew nearer for the canoe families that were traveling from the different tribal communities, who were getting ready to leave, they thought to themselves, “Why am I going?” Many of our youth were seeking identity. Many of our young ones are wanting to be on a healing journey that brings them back to who they really are. Many of our Elders go on journey to witness this rebirth and to stand proud with how we survived the annihilation of our societies. And together they created a bond that made us realize that what we're doing today is a result of all those things that our ancestors tried to say for us in years past.

[A man places a necklace around a woman in a life jacket on a canoe. People sing and paddle.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: Being on Canoe Journey is a healing. It's a healing for oneself, but most importantly it's a healing and a prayer for those that are being left behind, those in your mind and your heart that you know are suffering. And you send those prayers with every stroke that you take, every breath that you take, and it's all good when you do this with one mind and you travel towards your destination.

And so the journey begins and the paddlers take off from their village and their community to make their way to Lummi. And when they're on the water they feel a certain spirit move over them—this feeling of being home, this understanding of, like, this is the way it always used to be, this complete manner of being because now you're one with the water, you're one with the canoe highway that our ancestors traveled in search of food, in search of shelter, in search of new friendships. And that's really what canoe journey is trying to relive today.

[Two canoes meet. Men in boats shake hands.]

MAN: Jake, right?

LARRY: Larry.

[Hundreds of people line the shore, awaiting the canoes’ arrival.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: The flotilla grew and grew as the weeks have passed, until finally when they landed at Lummi there were over 104 canoes. This was the 30th anniversary of the canoe journeys and it being a recent occurrence has become a way of life for a lot of our people in the Coast SalishTerritory.

[Map of Paddle to Lummi journey. People singing and dancing.]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: You know when you're saying Salish, I think that's kind of- that's what we're talking about is the people around here that were in those canoes. All them Tribes with the “-ish” at the end. We're all family, we're all related. When you're saying Salish that's kind of the idea I grasp.

[Map of Alaska area and images from around the Columbia River. Archival images. Preparations for the contemporary potlatch.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: But also up and down the Pacific Coast from as far north as Bella Bella and into Alaska, and as far south as the Columbia River and the Columbia Indian Tribes who prepare themselves throughout the year to come to tribal canoe journeys. They practice their song and dance, they prepare for the potlatch, and they prepare to see old friends and make new friends. With Journeys we have the opportunity to witness the growth of the language and culture through our children.

[Children performing dances and singing]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: [unknown] I see the people following the sacred path that's been set out for them for generations since time immemorial and I see them grabbing on to this sacred medicine and using it to the best of their ability.

[People singing and paddling canoes.]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: I see highly respected women not fearing this bad world, this scary world. I see these, you know, young men doing the best they can to be who they are.

[People dancing and singing.]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: We are all just people and we're all trying to be, we’re all trying to live, you know, be happy and seen and be able to grasp onto things that were taken at one point. [unknown] You can see the pride on their face.

[Canoes and hundreds people on shore.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: So here we are in 2019 on the 30th anniversary of Canoe Journeys and the people recognize the strengths that have been gained through Canoe Journeys—how it informs the work that we do with our children, how it preserves those things that were dear to our ancestors, the way we sing and dance and speak to each other with a good heart and a good mind.

[People gathered, singing and celebrating.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: Leaders in our community gathered themselves their families and their children to prepare, practice song and ceremony for the giveaway. The good minds and the good hearts made sure that there were places for the people to camp and to be fed and to ensure that the health and well-being of our Elders were looked after, and also that when our people stepped onto the floor that everybody was welcome.

[Hundreds of people onshore, cheering the arrival of canoes]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: When that day arrived and the canoes paddled into the shores of the Lummi Nation, they came to shore and they recognized the Lummi people and they asked the Lummi people if they could come to their shores and practice song and ceremony and the power of the giveaway with the Lummi people. Asking if they can come to see their relatives once again and to recognize that these things that we're doing today had always been a big part of our way of life.

[Canoes near shore, people ask permission to come to land.]

MAN IN CANOE WITH MICROPHONE: We ride on the [unknown]. I give all the glory to our Nooksack youth. They wear our power that got us here today. And I'm- I want to- I want to say it's an honor to be on Stommish grounds. So much tradition and culture has been shared here. I would like to share some of our songs and our culture with you. We humbly ask permission to come ashore to all my relatives.

WOMAN IN CANOE WITH MICROPHONE: We thank you very much. Thanks to the Lummi Nation for allowing us passage through your waterways. We would like to come to shore to share songs, to share dance, to share good medicine with you. [unknown]

MAN IN CANOE WITH MICROPHONE: I'm here speaking for OnePeople's Canoe Society who has members from all over Alaska—both Native and non-Native and we humbly request permission to come ashore so we may share in your festivities to sing and dance alongside you.

MAN ON SHORE: On behalf of the Lummi Nation, we're so thankful that you're here. We're so thankful that you come here to share of meal, to share your songs, to share your dances, and to share your good feelings. We're so thankful that you're here. We want to invite you to come ashore.

[People celebrating together, singing and dancing. Children dance.]

DARRELL HILLAIRE: It is so important for our people to know that hosting Canoe Journeys does something for all of the Lummi people, especially our children who are experiencing this whole idea of becoming a Lummi that speaks the language, that practices the song and the dance of the old people and learn the importance of giving themselves and giving to others those things that come from the heart.

[People sing and dance.]

[MUSIC—RATTLES, SINGING, AND DRUMMING]

TYSON SCARBOROUGH: For me, Canoe Journey was more than just a modern-day Natives’ gathering and celebrating bringing back that potlatch. Because I I heard stories from my Great-Grandmother on how all our regalia was literally ripped up and just thrown into the fire. So, you know, for [unknown], for all of our people to gather and you know be able to wear that sacred regalia again, it brings some good feelings, some [unknown], some sacred feelings, I guess you could say. It jolts medicine through my body almost it feels like.

DARRELL HILLAIRE: Looking back at the last great canoe journey of our people, much was lost and today is being reborn, recaptured, if you will, this life way of living on the water, understanding what the water does for our people, giving us life for the salmon that we receive, giving us life for the songs that we receive, giving us life for the understanding that our Ancestors live along these shores and their spirit still lives today. And our children are recognizing that very thing.

SPEAKER: [unknown]

[ON-SCREEN TEXT: Friends and relatives, on behalf of Lummi Nation, on behalf of our elders, I want to thank each of you who answered the invitation, and paddled here to Lummi. I want to thank each of you for bringing your good feelings. I want to thank you all for sharing your songs and your dances with our community. We hope that when you make your journey back home, you find your homes the way that you left them. On behalf of Lummi Nation with all of my heart, I raise my hands to you. Hy’shqe Siem.]

[Credits roll]

Lushootseed Language

Lushootseed is the language of the Duwamish, Nisqually, Puyallup, Skagit, Suquamish and many other Native Nations along Puget Sound, Washington. Click on the audio players below the images to hear Lushootseed words spoken by q̓ʷat̕ələmu Nancy Jo Bob.

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/1642

AMNH Anthropology catalog 50.2/457 A-K

AMNH Anthropology catalog 50.2/901 A-C

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/8854

sč̓ədᶻəp | Cedar skirt

slahaləb | Game

staʔɬ | Harpoon

ƛ̕ak̓ʷtəd | Needle

More Resources

Coast Salish Consulting Curator

secəlenəχʷ | Morgan Guerin, Musqueam

The Museum thanks Dianne Hinkley and the Quw’utsun’ community for the Hul’q’umi’num’ words included in this text, q̓ʷat̕ələmu Nancy Jo Bob, qəɬəblu Tami Hohn, and dᶻagʷabidic̓aʔ Michele Balagot for the Lushootseed words included in this text, Alyssa Johnston, Cosette Terry-Itewaste, and Adrian Underwood-Vitalis for the Quinault words included in this text, the Musequeam community for the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ words included in this text, and Kathy Cole and the Grand Ronde community for the Chinuk Wawa words in this text.