Shackleton

January 1, 1999 — October 11, 1999

The exhibition was made possible by a major gift from Mr. and Mrs. Joseph F. Cullman, 3rd.

January 1, 1999 — October 11, 1999

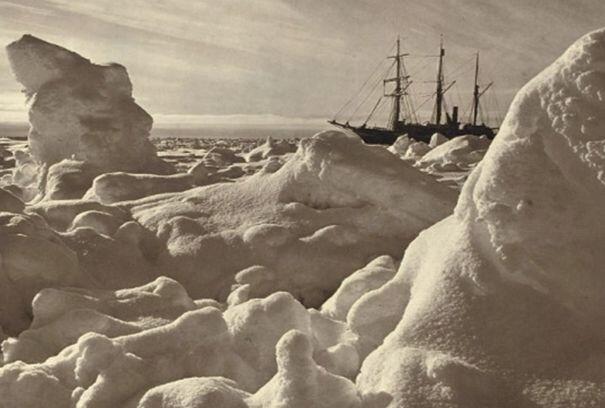

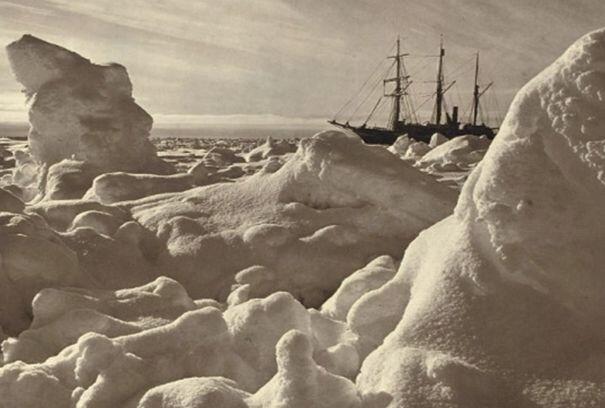

Frozen fast for ten months, the ship was crushed and destroyed by ice pressure, and the crew was forced to abandon ship.

After camping on the ice for five months, Shackleton made two open boat journeys, one of which—a treacherous 800-mile ocean crossing to South Georgia Island—is now considered one of the greatest boat journeys in history. Trekking across the mountains of South Georgia, Shackleton reached the island's remote whaling station, organized a rescue team, and saved all of the men he had left behind.

The Exhibition, on view from April 10–October 11, 1999 at Museum, documented one of the greatest tales of survival in expedition history: Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914 voyage to the Antarctic.

The Shackleton exhibition featured more than 150 compelling photographs by expedition photographer Frank Hurley in the most extensive presentation ever mounted on this dramatic journey. Many of the images were on view for the first time, displayed alongside diary excerpts and expedition artifacts, including the actual lifeboat used in the epic boat journey, as well as rare color images and film footage by Hurley. The exhibition also included sections on the journey's historic and geographic context, and an immersive computer simulation on navigation.

Although this was primarily an exhibition of photos and film footage, the centerpiece was the James Caird. As visitors reached this point in the story, they come upon the boat itself, surrounded by a high-resolution projected simulation of the ocean. Dead ahead, low on the horizon, a faint sun peeks through the clouds. To the stern of the Caird, in a glass case, was the sextant used by Frank Worsley in his incredible navigational feat. On either side, mounted on pedestals, were two sextants that visitors used.

The sextants are real, World War II-era relics, and the fact that they still work after all these years testifies to their sturdiness for use in the exhibition. Mounted beneath each sextant, an LCD monitor gave step-by-step instructions. When the visitor took a sighting, sensors embedded in the sextant sent information to a computer, which calculated the visitor's sighting. The resulting position was displayed on the screen, compared with the actual path of the Caird. The calculation was accurate, the same one Worsley used, except that his was done with a broken pencil and a wet notebook.

Technically, this interactive simulation was a new direction for the Museum. This was anything but a traditional computer kiosk; the only means of interaction was with the sextant itself, and the overall feeling was that of being far out at sea. The projected ocean surrounding the Caird had fooled many visitors, who asked where and how it was filmed. In fact, it was completely computer-generated and was a seamless ten-second loop. The motion had to be calibrated carefully; early tests could easily make someone seasick. The final version gave a strong sense of rocking motion, although it was nowhere near the 60-foot seas encountered by Shackleton and his men.

The exhibition was made possible by a major gift from Mr. and Mrs. Joseph F. Cullman, 3rd.