What we call a “hurricane” is called a “typhoon” in Asia and a “cyclone” in the South Pacific. But they’re all the same thing: a rotating storm that forms in the tropics (near the equator) and has winds of at least 120 kilometers per hour (74 mph).

What causes hurricanes? How do scientists study them?

Let’s find out.

Hurricane Sandy Storms Into New York City

In late October 2012, Hurricane Sandy devastated parts of New York City and the surrounding area. The hurricane was huge, but it was not the windiest storm to ever hit the area. Sandy’s biggest threat was the huge pileup of water — called a storm surge — those winds produced. On top of this, the massive storm surge hit at almost the same moment as an unusually high tide.

New York City has 835 kilometers (520 miles) of coastline, much of it low-lying, so officials expected flooding. But the deluge was worse than anyone thought it would be. In lower Manhattan, seawater poured over floodwalls, flooding roads, subways, and electrical stations. Many were left without transportation or power. The seaside communities were hit worst. As waves crashed into the coast, the storm surge flooded homes and businesses, destroying entire neighborhoods. In the end, the storm took 43 lives, and left many people injured and without homes. It also caused at least $19 billion in damage.

Take a look at different areas that were impacted by Hurricane Sandy.

Mantoloking is a barrier island on the New Jersey shore, about 95 kilometers (60 miles) south of Manhattan. These images, taken before and after the hurricane, show how storm waves cut across the island, eroding the beach and destroying houses and roads.

Compare these two views of Mantoloking before and after the storm.

Coming Together

Many helped with relief efforts. The National Guard, Red Cross, local agencies, and citizens streamed across New York and New Jersey to remove debris and distribute emergency supplies to those in need.

Troops handing out supplies to people at an emergency shelter in Piscataway, NJ.

What causes a hurricane?

A thousand miles across, Hurricane Sandy was the largest North Atlantic hurricane ever recorded.

Find out how the Sun’s heat and Earth’s rotation can turn a simple thunderstorm into a fierce, swirling hurricane.

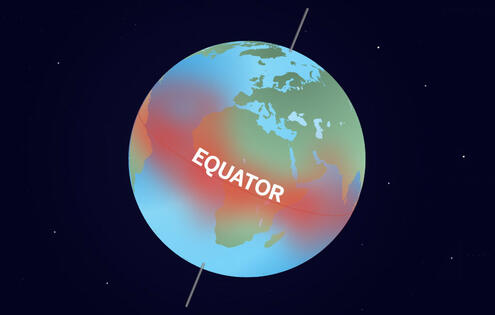

How do hurricanes form? In the simplest terms, the Sun’s heat and Earth’s rotation lead to hurricanes. Near the equator, the Sun’s intense rays warm vast areas of ocean.

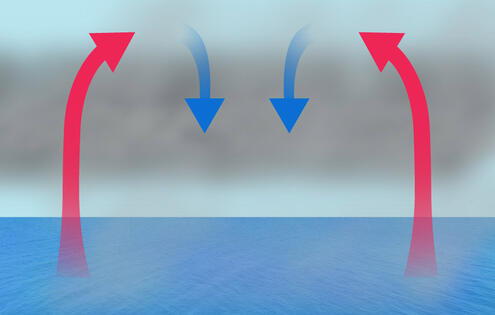

The Sun’s heat causes ocean surface waters to evaporate. The warm, moist air rises, cools, and condenses to form clouds. If the air is warm enough, large thunderstorms can form.

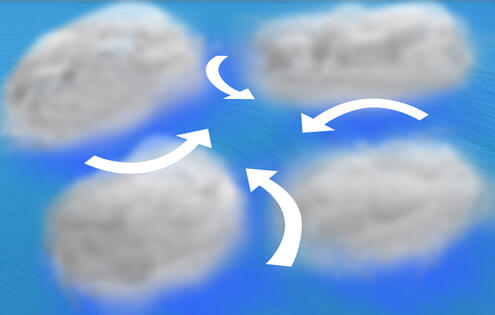

Several large thunderstorms cluster together. Earth’s rotation causes the winds to swirl around its center and wind speed to increase.

If wind speeds increase to 63 kilometer (39 miles per hour), it becomes a tropical storm. If winds reach 120 kilometer (74 miles per hour), it becomes a hurricane.

As a hurricane travels over warm ocean waters, it is fueled by heat and water. As it moves over land, its heat supply is cut off and the powerful storm weakens.

How do scientists track and predict a hurricane?

Satellites: Tracking Storms from Space

Not long ago, hurricanes would arrive without warning. But since the 1960s, satellites have helped meteorologists identify and track developing storms. Infrared sensors on satellites reveal information about temperature and humidity — conditions linked with hurricane formation. Today, satellite data can be transmitted in seconds.

Hurricane Hunters: Collecting Data in the Heart of the Storm

Hurricane Hunter aircraft are packed with instruments and sensors to collect information from the heart of the storm.

Specially trained pilots called “Hurricane Hunters” fly right where the action is: into hurricanes. Instruments on the planes collect information on wind, rain, air pressure, and temperature. The data is sent from onboard computers to the National Hurricane Center, where it is used to forecast the path and intensity of the storm. This information helps determine which areas should be evacuated.

Computer Models: Predicting a Hurricane’s Path

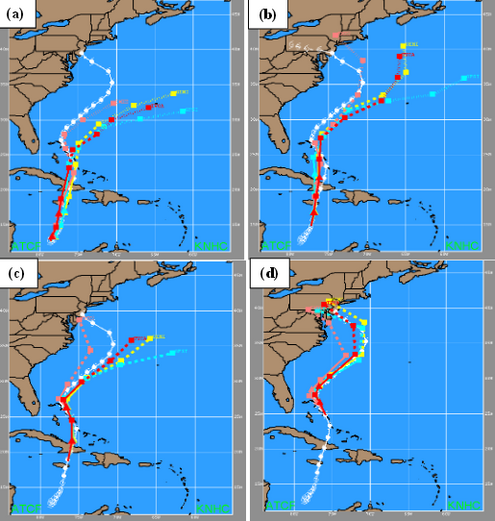

These images show the predicted tracks for Hurricane Sandy on four consecutive days in October 2012. The white line shows the storm’s actual path, while the colored lines show tracks forecasted by different computer models.

Meteorologists enter data from satellites, aircraft, and weather stations into a computer model. They use these models to predict the formation, path, and strength of hurricanes. They also use the models to predict a hurricane’s storm surge and potential flooding.

Preparing for a Disaster

KNOW what types of disasters could happen in your community. Know the warning signals and evacuation plans.

PREPARE a disaster plan for your family that includes where to meet, who to call, and what to do with pets.

PRACTICE your plan to make sure everyone knows what to do.

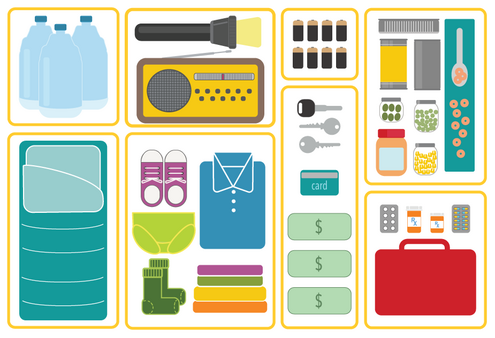

KEEP a disaster supply kit on hand.

A disaster supply kit should include:

- A three-day supply of water — one gallon per person, per day

- Enough non-perishable food for three days

- One change of clothing and shoes per person

- Medications Blankets and sleeping bags

- A first-aid kit

- Flashlight and extra batteries

- Battery-powered radio

- Extra set of car keys and a credit card or cash

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water