Scientists travel around the world to observe many different animal species and to collect their DNA . By analyzing DNA, scientists can figure out the kinds of animals that live on our planet, where they live, and the ways in which they’re related. This information helps protect endangered animals and the habitats they live in.

Check out these scientists' journals from around the world!

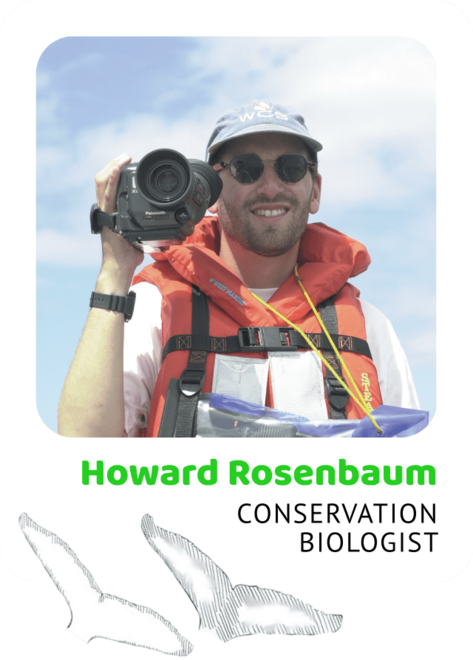

Preserving Humpbacks is No Fluke

For centuries, humans have hunted humpback whales. There are only about 35,000 humpbacks left in the world. I’m Howard Rosenbaum , and I hope that my research will help preserve this endangered species.

In my research, I travel to Madagascar to observe humpbacks . I can tell the whales apart by their different flukes. Flukes are the broad, flat ends of a whale’s tail.

Through careful observation, I can recognize more than 500 different whales.

By comparing DNA analyses with my field observations, I can see how the whales are related and how they interact with each other. Then, I will be able to recommend how we might protect these amazing animals.

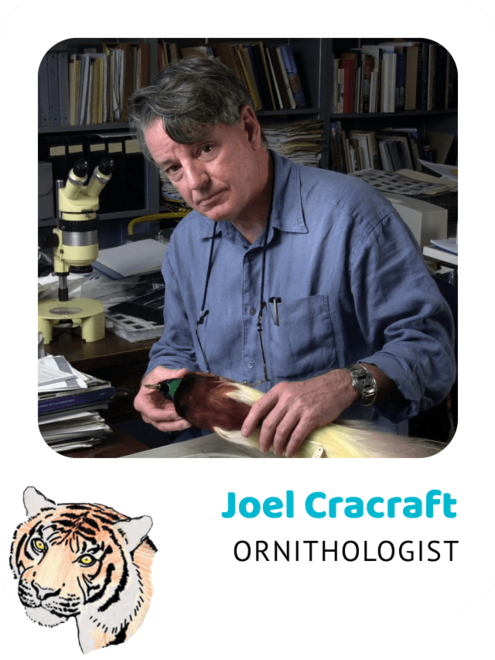

The Big Cats of Sumatra

Hi, I’m Joel Cracraft . I study birds at the American Museum of Natural History, but I’m also crazy about tigers. I’ve used genetics to study a type of tiger that lives on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia. Several thousand years ago, the islands of Indonesia were connected to mainland Asia, and all the tigers roamed freely. Gradually, the islands separated and Sumatran tigers became isolated.

My team compared the DNA of Sumatran tigers to that of other kinds of tigers, such as Bengals and Siberians. We discovered that Sumatran tigers are genetically unique. Scientists can use this information to make decisions about how to breed tigers in zoos. This discovery will also support Indonesia’s efforts to protect tigers in the wild.

Whooooo's Life is it Anyway?

I'm George Barrowclough and I investigate spotted owls. These magnificent birds live in the western United States, where they nest in the largest, oldest trees. I am worried that northern spotted owls may become extinct because the forest that is their home is being cut down.

I analyzed DNA taken from blood samples of northern spotted owls and California spotted owls to see if these bird species are different. I concluded that they are. The government is considering my DNA evidence as they figure out how to preserve the northern spotted owl.

What's Black and White and Fluffy All Over?

The answer to this riddle is one of my favorite animals. My name is Yael Wyner , and I study black-and-white ruffed lemurs . These small, furry mammals live in Madagascar, an island off the southeast coast of Africa.

Many forests in Madagascar have been destroyed because people need land for grazing and farming. So now lemurs are endangered. Scientists want to prevent these marvelous creatures from becoming extinct . So they are sending lemurs that have been bred in U.S. zoos back home to their native Madagascar.

Scientists hope that the imported lemurs will mate with the native ones, and that the population will gradually increase. In the lab, I analyzed the DNA sequences from several lemurs from both Madagascar and U.S. zoos. Scientists are using my results to help track how the “zoo lemurs” are adjusting to their new habitat over time.

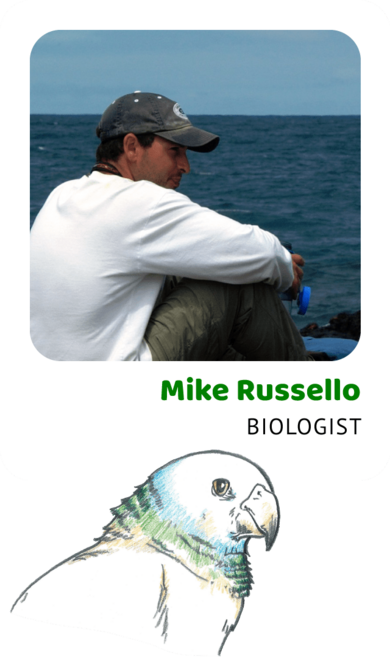

We Want Future Generations to Inherit the Parrot

I’m Mike Russello and I’m a graduate student. I also work at the American Museum of Natural History. I study a bird named the St. Vincent parrot . It's named the St. Vincent parrot because it makes its home on the island of St. Vincent in the West Indies.

Many people want to keep these rare, colorful birds as pets. One bird can sell for $10,000! So, sometimes people try to smuggle them to countries around the world. The forest where they live is also being destroyed. This illegal trade and habitat destruction have made the St. Vincent parrot an endangered species. Scientists now think that there are only about 500 individuals on the island.

We want to conserve this precious animal. To do this, we need to protect the forest. We also need to help the St. Vincent parrot population increase. So, we breed them. But it’s not that easy. Male and female parrots look exactly the same. In the past, the most common way scientists discovered whether a parrot was male or female was through surgery. But now we can study DNA from a bird’s feathers to see whether it is male or female. DNA analysis can also tell us which birds are the best matches. We want to breed the birds so that there’s variation in the gene pool. The greater the genetic differences within a species, the greater the chances that it will survive - today and in the future.

How to Avoid a Pacu Snafu

Do you ever wonder if there's something we could do to make sure an animal doesn't become endangered? I'm Daniela Calcagnotto, and that's exactly what I'm trying to figure out.

I study a species of fish called the pacu . These fish are close vegetarian relatives of the meat-eating piranha. They are found in several rivers in South America. They can grow to be as heavy as a human kid - that's about 50 pounds! The pacu is very important to the economy of many communities. Recently the wild populations have been overfished and their numbers are decreasing.

The Brazilian government approved a project to study the pacu populations to see how the fish vary from river to river. As a first step, I took little pieces of fin from various fish and removed DNA. Now, I am comparing the DNA to see how genetically different, or diverse, the populations are. Scientists need this information to breed fish in fish farms. They want the farm populations to have the same genetic diversity as the wild populations. If the fish become endangered, we can then help the populations grow again. We can gradually move the fish from the breeding place to the rivers.

Image Credits:

Photos: George Barrowclough: courtesy of R.J. Gutierrez; Humpback whales, Howard Rosenbaum: courtesy of Peter J. Ersts, Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, AMNH; Owl: John and Karen Hollingsworth, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Yael Wyner: courtesy of Yael Wyner; Joel Cracraft: courtesy of Joel Cracraft; Sumatran Tiger: courtesy of Jessie Cohen, Smithsonian's National Zoo; Lemur: courtesy of Duke University Primate Center; Daniela Calcagnotto: Courtesy of Daniela Calcagnotto; Pacu: courtesy of Leonard Lovshin, Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures, Auburn University; St. Vincent parrots, Mike Russello: courtesy of Mike Russello; Illustrations: Louis Pappas, Steve Thurston, Eric Hamilton.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water