Fossilized bones digested by crocodiles in the Cayman Islands included three new-to-science species of extinct mammals.

Fossilized bones digested by crocodiles in the Cayman Islands included three new-to-science species of extinct mammals.© NMMNH

The last meal of crocodiles in the Cayman Islands has provided key evidence for scientists to describe three new species and subspecies of extinct mammal that once lived in the Cayman Islands more than 300 years ago.

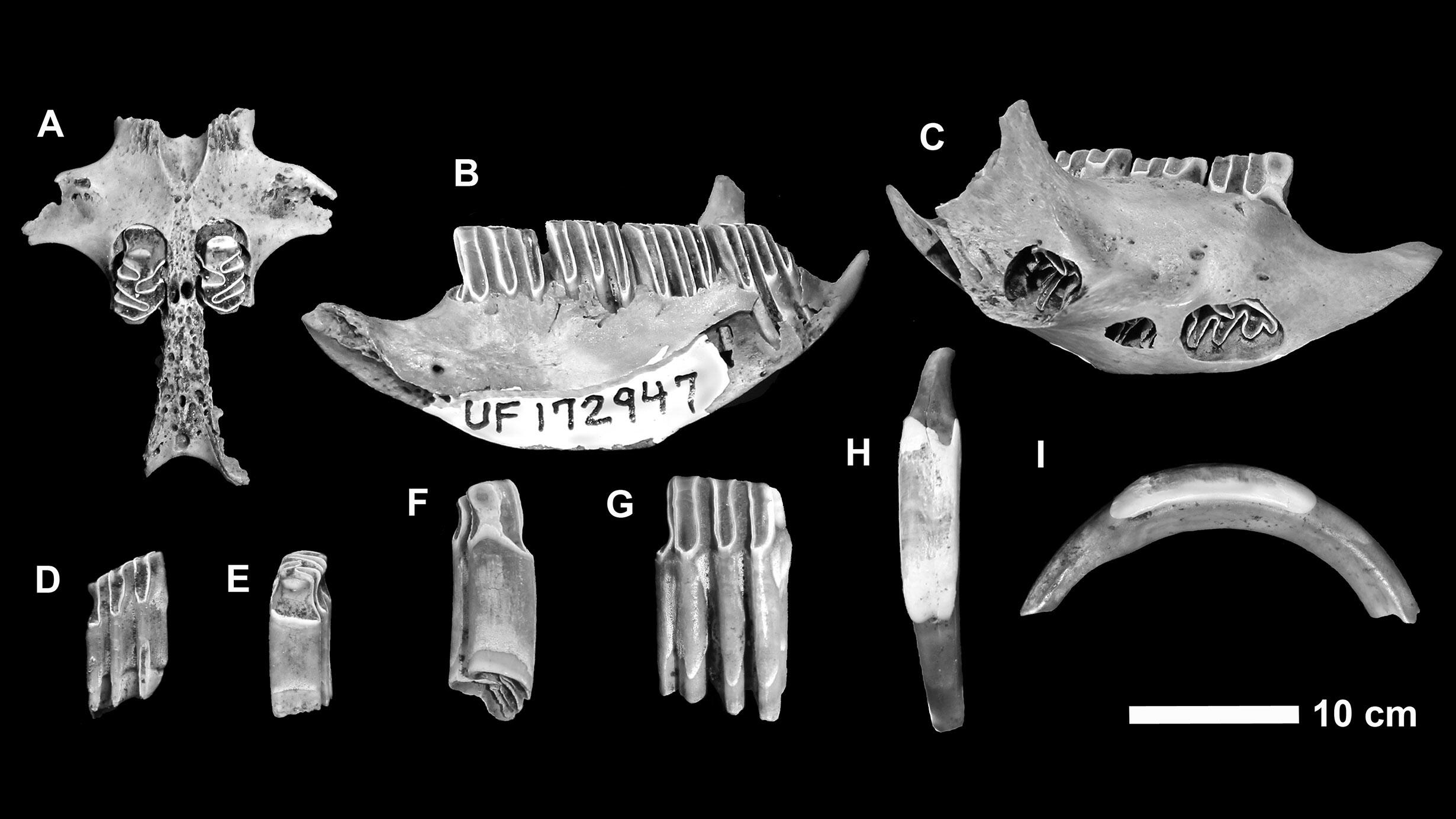

The animals, described in a recent study published in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, include two large rodents, Capromys pilorides lewisi and Geocapromys caymanensis, and a small shrew-like mammal named Nesophontes hemicingulus that were endemic to the islands.

"Although one would think that the greatest days of biological field discoveries are long over, that's very far from the case,” says Ross MacPhee, curator in the Museum’s Department of Mammalogy and co-author on the study. “With only one possible sighting early in the course of European expansion into the New World, these small mammals from the Cayman Islands were complete unknowns until their fossils were discovered.”

The first recorded sighting of the now-extinct Capromys and Geocapromys was by Sir Francis Drake during his visit to the islands in 1586, when he dubbed the animals “coneys” and “little beasts like cats.” The rodents’ closing living relative, Capromys pilorides, can still be found in Cuba today. Researchers suspect that mammals may have originally floated from Cuba to the Caymans on floating vegetation.

© Nancy Albury

The team estimates that the mammals all went extinct around the 1700s, with the arrival of European settlers and animals they brought with them, such as cats, dogs, and rats, the likely cause.

“Humans are almost certainly to blame for the extinction of these newly described mammals, and this represents just the tip of the iceberg for mammal extinctions in the Caribbean,” says Samuel Turvey, senior research fellow at the Zoological Society of London’s Institute of Zoology and co-author of the paper. “It’s vitally important to understand the factors responsible for past extinctions of island species, as many threatened species today are found on islands. The handful of Caribbean mammals that still exist today are the last survivors of a unique vanished world and represent some of the world’s top conservation priorities.”

The arrival of Europeans in the West Indies had such a profound effect on local wildlife that only 13 endemic mammal species, in addition to 60 species of bat, now survive there. During the Quaternary Period, between 0.5 and 1 million years ago, the islands would have been home to nearly 130 mammal species, including sloths, monkeys, and rodents, among others.