Shelf Life 04: Skull of the Olinguito

MIGUEL PINTO (Mammalogist): Otonga is located in Ecuador. Probably it is the most beautiful place that I have seen.

You can hear the drops of water just fall from the leaves and the branches. You can see the orchids.

And suddenly, when you are walking you just hear this vroom, vroom, vroom, and those are actually hummingbirds you cannot see because the mist is so dense.

It’ s the magical land of the olinguito—the first new species of Carnivora found in decades.

I am Miguel Pinto. I study mammals and mammalian parasites.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

PINTO: The olinguito is a new species that was discovered using museum collections.

The specimens here in the American Museum of Natural History were collected in the early 20th century, but they were not studied.

NANCY SIMMONS (Curator-in-Charge, Department of Mammalogy): New species are very often found in the drawers of museum collections—basically hiding in plain sight, amongst all the other material.

I’m Nancy Simmons. I’m the Curator-In-Charge of the Department of Mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History.

When researchers go out in the field and make general collections—and this happened a lot back in the early 20th century—they would collect everything that they could. Now, when that came back to the museum, there might be a specialist here who worked on the rodents, somebody else might work on the carnivores, but maybe, for instance, the bats just got filed away. So, only years later when somebody who’s interested and knowledgeable about those particular species comes back and looks closely at them, they go, “Wow, there’s something new here that nobody noticed when it first came into the collections.”

KRISTOFER HELGEN (Curator-in-Charge of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History): My name is Kristopher Helgen, and I’m a curator of mammals at the Smithsonian.

It was end of the year, 2003. I was working in the Chicago Field Museum, studying members of the raccoon family. I pulled open a particular drawer, and I saw these red-orange pelts that were so different from any other raccoon family member I’d ever seen. They stopped me in my tracks. I pulled open some of the boxes of skulls that went along with those skins. And all of a sudden I started to see differences in teeth and skulls

And it occurred to me right there and then—could this be a kind of mammal that all other zoologists had missed. And that’s where it all started.

I wanted to go to every museum in the world that could conceivably have these. This was the second largest holding of these animals.

PINTO: The museum data probably was enough to describe this new species. But we wanted more information. We wanted to see if there were still living populations in the wild.

So, Kris organized a group of researchers. And so I got involved to go to the field and find these guys. Looking at the data associated with the museum specimens, we could understand more or less the kind of forest where the olinguitos were living.

I could say, “Well, Otonga might be a very good place for these animals.” So, I did some scouting trips and it turn out to be the right place.

The first night in this forest, in Otonga, I could see the olinguito. Actually it was jumping over my head on the branches. That was amazing.

SIMMONS: When a researcher thinks they have a new species and wants to describe it in a formal way, they need to pick out a holotype—that is a single, individual specimen that is going to represent that species for all time.

A good holotype isn’t necessarily the prettiest or the biggest specimen.

In history, typically, male researchers often picked male holotypes. But really it doesn’t matter. It can be either a male or a female. Ideally, a holotype is a complete specimen of an animal. However, often holotypes are not complete. For instance, with fossils, a holotype can be just a couple of teeth of an extinct animal.

HELGEN: We grapple with, you know, which specimen should be the type. With the olinguito because our work in the field and our work with DNA was based on the Ecuador samples, we really wanted to pick a type specimen from Ecuador. And so, the best one, that turned out to be here at this museum. It’s been here a long time and we know it’ll always be here.

The olinguito is by no means the only holotype of a mammal in our collections. We have over 1200 type specimens here, of things ranging from bats and shrews to whales and elephants.

Holotypes are really important because new discoveries of species diversity are based on comparisons to past species diversity.

HELGEN: With so much life on our planet, we’re constantly using these important reference points in museums to sort out the variation and richness of life on Earth.

PINTO: With the olinguito, visiting all these collections, analyzing all the data, and putting it all together—I think that is great museum science. It’s such a rare privilege to describe a new species and the olinguitos are just beautiful, beautiful animals.

New species are discovered all the time, and sometimes they’re found in the drawers of museum collections, basically hiding in plain sight.

-Nancy Simmons, Curator-in-Charge, Department of Mammalogy

Oh, the Species You'll Find

Scientists have identified more than a million and a half species of plants, animals, fungi, and microbes on the planet, but that’s just the beginning. The vast majority of species have yet to be discovered, named, and categorized. According to recently published estimates, there are more than 7 million species we have yet to identify.

Thousands of those species are being described each year, from single-celled organisms found in pools of volcanic sulfur (or your own stomach) to deep-sea organisms and larger animals like primates and birds. Expeditions are one of the primary ways to find animals not yet known to science, so researchers regularly head out to far-flung corners of the globe for a chance to spot new species.

But while scientists may have a hunch about a specimen in the field, the actual discovery is more commonly made in scientific collections—often years after collections are brought back and filed away. On average, more than two decades pass between the first collection and archiving of a new species and its formal description.

What accounts for the delay? For one, the sheer volume of the collections. Major expeditions in the early 20th century routinely brought thousands of specimens into the Museum’s collections, and researchers are still playing catch-up. Also, the team bringing back a set of specimens may not necessarily have had the expertise to recognize a new find.

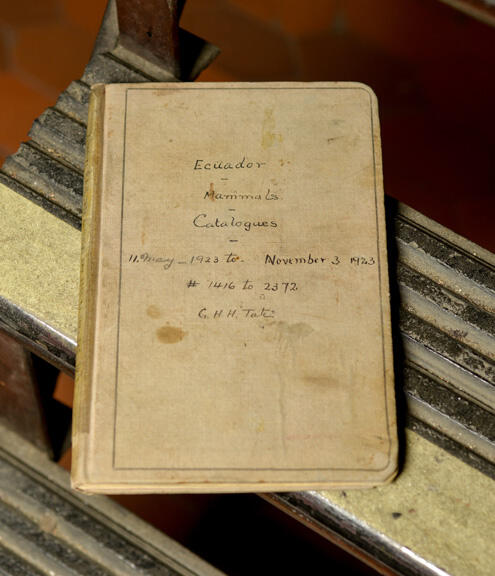

© AMNH/Department of Mammalogy Archives

“There might have been a specialist here who worked on the rodents, somebody else who might work on the carnivores,” says Nancy Simmons, curator-in-charge of the Department of Mammalogy. “But maybe the bats just got put in the drawer and filed away. Only years later, when somebody who’s interested and knowledgeable about those particular species comes back and looks closely at them, they go, ‘Wow, there’s something new here.’”

The field journals of the Anthony-Tate Expedition are still in the Museum’s holdings, as are the specimens collected during the trip.

The field journals of the Anthony-Tate Expedition are still in the Museum’s holdings, as are the specimens collected during the trip.D. Finnin/© AMNH

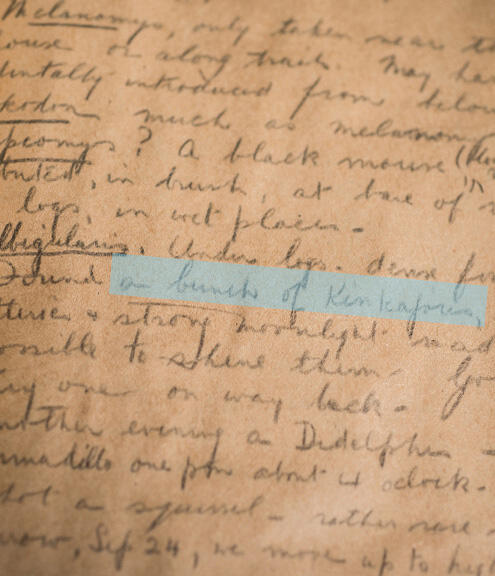

A page from the Anthony-Tate expedition field notes details the collection of the first olinguito specimen, then identified as a kinkajou.

A page from the Anthony-Tate expedition field notes details the collection of the first olinguito specimen, then identified as a kinkajou.D. Finnin/© AMNH

That was probably the case with the olinguito, one of many mammals collected during the 1923 Anthony-Tate Expedition. A six-month journey into the rugged interior of Ecuador, this trip by Museum researchers aimed to improve understanding of the wildlife in the country’s then little-explored forests. While birds, reptiles, and fossils were collected, a special emphasis was placed on acquiring mammal specimens, of which more than 1,500 were collected—including 57 mammals in the course of one singularly productive morning. Considering the number of specimens collected during the trip, it’s little wonder that the olinguito—Mammal #66573, a raccoon relative originally identified as a kinkajou—spent nearly 90 years on the Museum’s shelves before being described as the new species Bassaricyon neblina in 2013. Its story isn’t unusual, either.

“There are, without a doubt, other new species of mammals waiting to be discovered in this collection,” says Mammalogy Curator Rob Voss.

top: © AMNH Library Services; bottom: B. Benz/© AMNH

But it doesn’t always take a lifetime to describe a new species. Other times, with the right team in the right place, an animal may be tagged right away as a potential scientific discovery, distinct from the millions of species already identified. That might be the case with one of the mammal specimens, and several amphibian and reptile specimens, recently brought back on the Museum’s latest Explore21 Expedition, a seven-week trip to the central highlands of the island nation of Papua New Guinea.

Satellite images by Earthstar

The team, which included ornithologists Brett Benz and Paul Sweet, herpetologist Chris Raxworthy, and mammalogist Neil Duncan, headed out to one of the world’s most biodiverse areas, trudging through largely undisturbed tropical rainforests to conduct detailed surveys of local wildlife. (You can get an insider’s look at expedition life in the team’s posts from the field on our blog.)

“It’s a region with amazing intact forests that we have very little biological data on,” says Raxworthy, noting that both of those factors gave the expedition a good shot at turning up some species never before described in scientific literature. The team used a variety of methods to collect specimens, including pitfall traps—plastic buckets buried in the soil that can collect ground-dwelling creatures—and mist nets, which can snare bats and birds.

P. Sweet/© AMNH

Duncan thinks one rodent, pulled from a pitfall trap by Papua New Guinea biologist Enock Kale, may represent a distinct species. While he’s careful not to make any claims that the specimen is unique before he’s done the significant work required to prove it, Duncan admits to being excited at the prospect of discovering a new animal.

“With millions of species named, one more would be a piece of a larger puzzle, but there’s still a degree of excitement associated with the idea,” Duncan says.

The work began in the field, when the skin of the specimen was removed, stuffed with cotton to maintain its shape, and dried. Back at the Museum, Duncan will be taking precise measurements of the rodent, part of the first step in distinguishing a species from a close relative by examining its morphology. The skull in particular contains a lot of information. Teeth, for instance, vary according to diet, and are slightly different in each mammal species.

© AMNH

Still, these variations can only tell us so much. Genetic analysis also plays a major role in identifying new species. Morphological data can be be backed up with genetic information that shows significant differences in DNA sequences between prospective new species and their known counterparts.

Researchers who think they have a new find can also look forward to a long trip through the scientific literature to see if it is in fact unique. This research phase sees scientists consult with other researchers and compare their specimens against similar samples here at the Museum and around the world.

If it does turn out to be a new find, the next step will be to name the new species. The naming process allows discoverers of new species to get a little creative (within the framework of binomial nomenclature, of course). For example, the olinguito’s species name, neblina, is taken from the Spanish for mist and inspired by the animal’s picturesque cloud-forest habitat.

Others use the opportunity as a shout-out to friends, loved ones, or Canadian rock stars. Exhibit A: the Neil Young spider (Myrmekiaphila neilyoungi), first identified in 2007 by East Carolina University biologist Jason Bond and Curator Emeritus Norman Platnick.

© American Museum Novitates/Bond and Platnick

(Would-be species namers, know this: it’s considered very bad form to name a species after yourself, so forget leaving your own moniker stamped in the annals of scientific discovery.)

Finally, researchers must identify a holotype, the physical example used in the species' formal description. Researchers look for the most complete specimen available, and one for which there is plenty of associated data. Knowing where and when an animal was collected can be extremely important for future study. There are more than 1,000 holotypes in the Museum’s mammalogy collection, and tens of thousands of holotypes in collections across the Museum’s other divisions.

© AMNH

The holotype is usually housed in a museum or similar institution so that researchers from the world over can access it regularly. And as information accumulates and research is done, it’s the holotype that ensures that researchers talking about the olinguito are discussing the same animal today and 90 years from now.