Shelf Life 12: Six Extinctions In Six Minutes

MIKE NOVACEK (Senior Vice Present and Provost of Science): Extinction is the end of a species. And millions of species have experienced extinction over time. In fact, probably 99.999 percent of all species that ever existed are no longer with us. Extinction is a way of life, actually.

But there’ve been mass extinction events where a whole array of species get wiped out and some biologists think that the current rate of species loss is probably a thousand times what the normal rate is.

I’m Michael Novacek. I’m the Provost of Science here at the Museum, but I’m also a curator of paleontology.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

NOVACEK: The collections in the Museum here and other museums are really a record of life—very important for not only telling us what went extinct, but what survived.

So, what follows are six tales of extinction—organisms with something to tell us about the time we’re living in now.

[LILTING MUSIC]

MELANIE HOPKINS (Assistant Curator, Division of Paleontology): My name is Melanie Hopkins and I’m an assistant curator in Invertebrate Paleontology.

Trilobites are a group of extinct marine arthropods. Arthropods include things like lobsters and insects.

There are sort of two main types of trilobite larvae. One appears to have been completely benthic.

Benthic just means crawling around on the ocean floor. And then there’s another type of larvae—planktonic—swimming or floating up in the water.

During the mass extinction at the end of the Ordovician, trilobite species with benthic larvae were more likely to survive. In some ways, this is surprising, because there are a lot of good things about having planktonic larvae. A big one being that it’s much easier to disperse further and ultimately end up with a larger geographic range.

This is a really good example of extinction selectivity. And what we mean by extinction selectivity is that during a major extinction event, there are some organisms that are more likely to go extinct because of some aspect of their ecology, like what they eat, or some other aspect of their lifestyle. Like, in the case of trilobites, whether they had planktonic larvae or benthic larvae.

By studying extinction selectivity in the fossil record, we can begin to understand what sorts of characteristics make some organisms more vulnerable to certain types of environmental change.

ALLISON BRONSON (PhD Student, Richard Gilder Graduate School): My name’s Allison Bronson. I’m a PhD student, studying fossil fishes at the Museum’s Richard Gilder Graduate School.

Dunkleosteus was a placoderm. Placoderms are fishes with bony armor that covered most of their body. And it lived during the late Devonian, from about 350 to 370 million years ago.

Dunkleosteus is just cool because it’s so big—estimates have ranged up to 20 feet long. It was really one of the first examples of a big, ocean-going predatory animal, occupying a role sort of similar to what we think of as a great white shark today.

Dunkleosteus went extinct, along with the rest of the placoderms, at the Hangenberg Event, which was a loss of almost 96 percent of vertebrate species at the end of the Devonian.

Dunkleosteus wasn’t the only large placoderm in the ocean at that time. But after this Hangenberg Event, we only see smaller animals in the fossil record. And this is part of what we call the Lilliput Effect.

The Lilliput Effect is something that we see at certain mass extinction events where before the extinction, animals are generally very large, and after the extinction, animals are generally very small. We still don’t really know what the explanations for this might have been, and there’s probably more than one.

AKI WATANABE (PhD Student, Richard Gilder Graduate School): My name is Aki Watanabe and I’m PhD student in the Richard Gilder Graduate Program here at the Museum, and also in the Division of Paleontology.

So, 65 million years ago, we had a meteorite impact on this planet, which led to the extinction of non-bird dinosaurs. We’re all familiar with that. But less familiar is the Late Triassic extinction event, that led to the extinction of a lot of early crocodilian relatives.

Early crocodilian relatives—we call this bigger group Pseudosuchians, which include modern-day crocs and their extinct relatives—they were actually really diverse in the Triassic. Like, you have herbivorous Aetosaurs with armor plates, you have Rausuchians, which have big skulls, like what you see, for example, on T. rex., and you also see bipedal forms, like Effigia.

So, at the end of the Triassic, Pseudosuchians are actually more diverse than dinosaurs. But, for some reason—still unclear—a series of extinction events happened at the end of the Triassic that led to more of an extinction in major groups of Pseudosuchians.

And then all these niches opened up that Pseudosuchians previously occupied. And so, dinosaurs were able to move into these niches and diversify and then thus the rest of the Mesozoic became the age of dinosaurs.

ROSS MACPHEE (Curator, Department of Mammalogy): I am Ross MacPhee. I’m curator of mammals at the American Museum of Natural History.

Horses are old in North America. They appeared roughly 50 million years ago, were very successful up until about 10,000 years ago when they disappeared in both North and South America, along with other Ice Age creatures.

But then 500 years ago, when the Europeans first came to these shores, they brought horses with them. And over time, horses escaped captivity and they’re still with us today. We call them mustangs in western North America.

But some people consider them invasive. And that’s really probably wrong. The lineage that gave rise to the domestic horse that we see here, you can trace back into their antecedents in North America. And from my point of view, that makes horses a native species.

Right now we’re perched on the cusp of being able to bring back extinct species and people are talking about bringing back mammoths and mastodons and sabertooth cats. But we don’t need to do that with horses. We have them right here, right now.

If you want to think of a Pleistocene Park, populated by Ice Age creatures, there is really none more appropriate than the horse.

SARA RUANE (Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Herpetology): I am Sara Ruane. I work at the American Museum of Natural History in the Department of Herpetology.

Golden toads are one of the most charismatic and beautiful looking frogs that have ever been discovered. And they were only discovered in the mid-1960s in the Monteverde Cloud Forest of Costa Rica. And what’s shocking is that 40 years later, by 2004, they were declared extinct. So, we only knew about these toads for a very brief period of time before they were absolutely gone.

While it’s still sort of a mystery what happened to golden toads, these are one of the first animals where climate change was heavily implicated in their demise. And that’s not entirely clear, but it’s likely that it’s a combination of reasons.

Maybe temperatures got a little too warm for these toads, and something like chytrid fungus, which affects a lot of amphibians could have then taken advantage and come in and decimated the populations.

So, one of the reasons collections are so important, is that we can go back and look at animals that have been collected in the past—even up to 100 years ago, 200 years ago—and test for some of the pathogens or the problems that are decimating amphibian populations today, see whether something like chytrid fungus is what caused their demise.

MARK SIDDALL (Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): I’m Mark Siddall, curator of invertebrates at the American Museum of Natural History.

The Guinea worm is a nematode parasite of humans and can grow to be about a meter in length inside of the infected person’s tissues.

Infection with Guinea worm is rarely fatal. But its effect does lead to malnutrition and starvation and other problems because when you have a meter long worm coming out of your knee with excruciating pain, you can’t take care of your family, you can’t go to school.

Driving human parasites to extinction is a moral obligation. The Guinea worm has caused millions of people to suffer, over hundreds of thousands of years, and in fact, it wouldn’t exist if there wasn’t a human out there to be its host.

Even as we drive human parasites to extinction, it’s really important to hold onto specimens in collections like ours, especially in our frozen tissue collection, because we want to preserve the genetic legacy of those parasites that we might better understand other parasites we’re trying to drive to extinction.

"Extinction is a way of life, but there have been mass extinction events where a whole array of species get wiped out."

-Michael Novacek, Provost of Science

Six (Mass) Extinctions in 440 Million Years

All things must pass. But the idea that a species could go extinct is a relatively new one, first proposed by anatomist Georges Cuvier in a presentation in Paris in 1796 in a lecture on the extinction of the mastodon, then thought by some to still be roaming the ill-explored western reaches of North America.

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

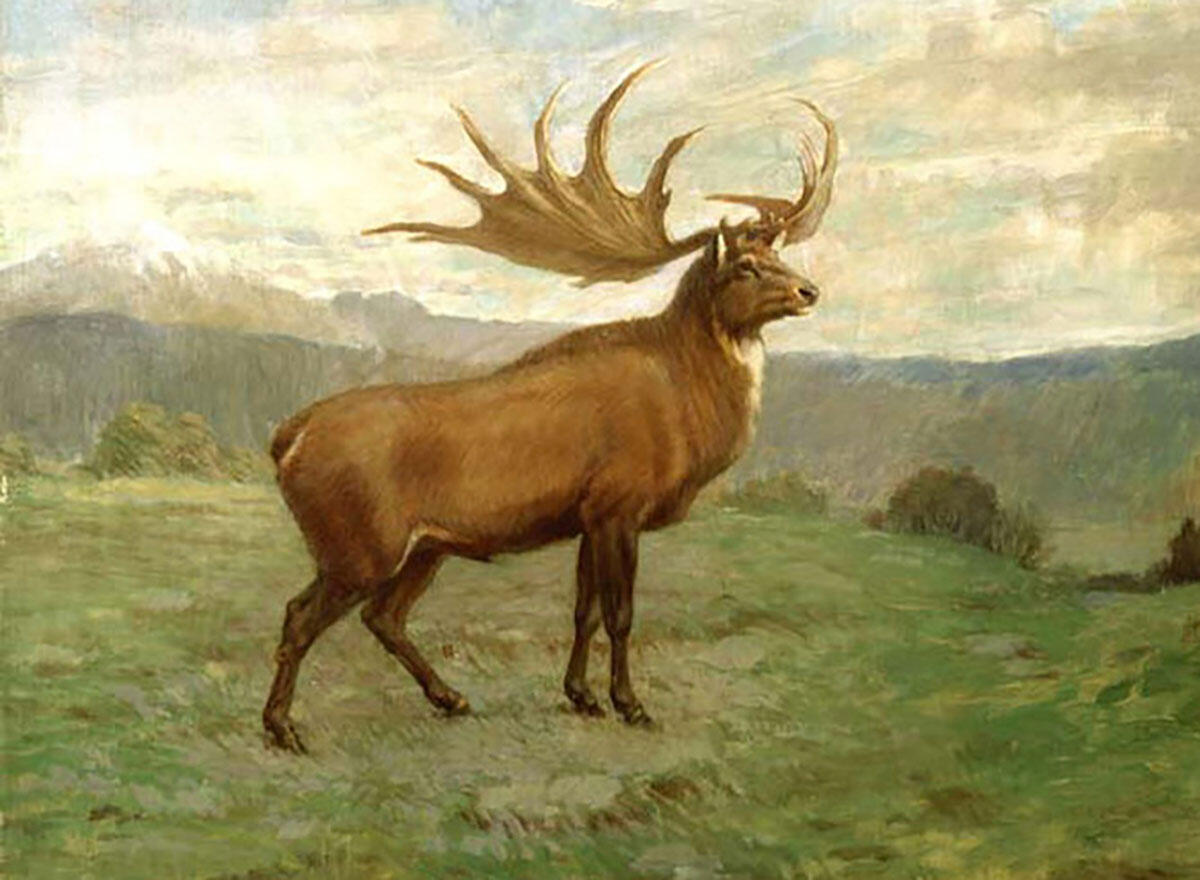

Cuvier’s suggestion that life on Earth was not static, and that species could disappear, was groundbreaking. Studying the collections of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and records from other collections around the world, he soon identified several species whose like we would never see again, including the mosasaur, the cave bear, and the Irish elk.

Buoyed by the research of scientists like Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, the idea that species developed gradually, over time, gained acceptance in the scientific community. For generations, it was dogma that extinctions happened slowly, too. The idea that species could be wiped out in a fell swoop, even one with catastrophic consequences, wasn’t given much credence.

That changed in the late 1980s and early 90s, with the Alvarez hypothesis, which stated that a huge comet or asteroid impact was responsible for the sudden disappearance of non-avian dinosaurs and many other forms of life 66 million years ago. Proposed by physicist Luis Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, the hypothesis took time to gain acceptance, but buoyed by evidence like the Barringer Crater pictured below, an extraterrestrial impact is now the most widely accepted explanation for the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction.

That acceptance also opened the door for further study of geological and fossil records, which led researchers to a surprising conclusion: While the K-Pg extinction event was a very bad day for life on Earth, it was by no means the only one on record. Researchers now think that the K-Pg was just the latest of five major extinction events—and that we’re currently in the middle of a sixth mass extinction, one caused not by a volcano or asteroid impact, but by humans.

Each event had a different impetus. Some took place over the span of millions of years while others were extremely sudden. What they have in common, though, is that they reshaped the face of life on Earth by wiping out a significant portion of it.

About 445 Million Years Ago: Ordovician Extinction

© AMNH

The earliest known mass extinction, the Ordovician Extinction, took place at a time when most of the life on Earth lived in its seas. Its major casualties were marine invertebrates including brachiopods, trilobites, bivalves and corals; many species from each of these groups went extinct during this time. The cause of this extinction? It’s thought that the main catalyst was the movement of the supercontinent Gondwana into Earth’s southern hemisphere, which caused sea levels to rise and fall repeatedly over a period of millions of years, eliminating habitats and species. The onset of a late Ordovician ice age and changes in water chemistry may also have been factors in this extinction.

About 370 Million Years Ago: Late Devonian Extinction

© National Science Foundation

Towards the end of the Devonian period around 370 million years ago, a pair of major events known as the Kellwasser Event and the Hangenberg Event combined to cause an enormous loss in biodiversity.

Given that it took place over a huge span of time—estimates range from 500,000 to 25 million years—it isn’t possible to point to a single cause for the Devonian extinction, though some suggest that the amazing spread of plant life on land during this time may have changed the environment in ways that made life harder, and eventually impossible, for the species that died out.

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

The brunt of this extinction was borne by marine invertebrates. As in the Ordovician Extinction, many species of corals, trilobites, and brachiopods vanished. Corals in particular were so hard hit that they were nearly wiped out, and didn’t recover until the Mesozoic Era, nearly 120 million years later. Not all vertebrate species were spared, however; the early bony fishes known as placoderms met their end in this extinction.

252 Million Years Ago: Permian-Triassic Extinction

The Permian-Triassic extinction killed off so much of life on Earth that it is also known as the Great Dying. Marine invertebrates were particularly hard hit by this extinction, especially trilobites, which were finally killed off entirely. But you don’t get a nickname like the Great Dying for playing favorites; almost no form of life was spared by this extinction, which caused the disappearance of more than 95 percent of marine species and upward of 70 percent of land-dwelling vertebrates.

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

So many species were wiped out by this mass extinction it took more than 10 million years to recover from the huge blow to global biodiversity. This extinction is thought to be the result of a gradual change in climate, followed by a sudden catastrophe. Causes including volcanic eruptions, asteroid impacts, and a sudden release of greenhouse gasses from the seafloor have been proposed, but the mechanism behind the Great Dying remains a mystery.

201 Million Years Ago: Triassic-Jurassic Extinction

This extinction occurred just a few millennia before the breakup of the supercontinent of Pangaea. While its causes are not definitively understood—researchers have suggested climate change, an asteroid impact, or a spate of enormous volcanic eruptions as possible culprits—its effects are indisputable.

Wikimedia Commons/Massimo Pietrobon

More than a third of marine species vanished, as did most large amphibians of the time, as well as many species related to crocodiles and dinosaurs.

66 Million Years Ago: Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction

The most recent mass extinction event is also likely the best understood of the Big Five.

Craig Chesek/© AMNH

In addition to its most famous victims, the non-avian dinosaurs, the K-Pg event caused the extinction of pterosaurs and extinguished many species of early mammals and a host of amphibians, birds, reptiles, and insects. Life in the seas was also badly disrupted, with damage to the oceans causing the extinction of marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, as well as of ammonites, then one of the most diverse families of animals on the planet.

In all, scientists estimate that 75 percent of species living at the time of the K-Pg extinction were wiped out.

Now: The Holocene Extinction

The Holocene Extinction hasn’t been defined by a dramatic event like a meteor impact. Instead, it is made up of the nearly constant string of extinctions that have shaped the last 10,000 years or so as a single species—modern humans—came to dominate the Earth. Some have even suggested that the Holocene Extinction would be more aptly named the Anthropocene Extinction, after the role humans have played in this ongoing loss of biodiversity around the world.

D. Finnin/© AMNH

Courtesy of NOAA/GLERL

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Many of the past mass extinction events are mysterious in some ways because we really don’t know the cause,” says Michael Novacek, the Museum’s provost of science and a curator in the Division of Paleontology. "But we have a good idea of what the cause of the current changes are, this century and the centuries before: it’s human activity.”

Humans have contributed to factors like climate change and the introduction of invasive species, which are leading to even more extinctions as animal habitats disappear or are disrupted by new species. “Some biologists think that the current rate of species loss is probably a thousand times what the normal rate is,” says Novacek.

Many of the species going extinct are doing so before they are even identified. In light of this, researching new species for a fuller understanding of the world’s biodiversity grows ever more urgent for institutions like the American Museum of Natural History. These records, Novacek says, are vital to our knowledge of the world around us.

“The collections in the Museum here and other museums are really a record of life," Dr. Novacek says. “They’re very important for not only telling us what went extinct, but what survived.”