Tools OF THE Trade

- An Archaeology Game -

Hi! I'm David Hurst Thomas and I'm an archaeologist. I went to St. Catherine Island in Georgia in search of a lost Spanish mission.

Hundreds of years ago, the Spanish built sites called missions for the Native Americans who lived in North America. Missionaries came to spread Christianity and to offer food and aid. Today, many of these missions are archaeological sites. They provide clues about how Europeans and Native Americans interacted with one another.

Like many kids in California, I visited these mission sites. When I grew up, I found out there were even more missions in the southeastern U.S. But no one seemed to know much about them.

The last account of the mission on St. Catherines Island was in 1687. How do you find a place that's been lost for over 300 years?

St. Catherines Island is located off the coast of Georgia.

Like all scientists, archaeologists have a special set of tools that help us do our work. Some tools like trowels , magnetometers , and total stations, are used in the field, where we excavate sites in search of clues. Tools like microscopes are used in the lab, where we examine what we find. Experts and local people are also valuable sources of information.

It took lots of tools (and many years), but my team discovered the lost mission. Want to hear how we did it?

Play this game to see how we discovered the lost mission on St. Catherines Island. In each box of the comic strip, pick the tool that helped us solve the problem.

Learn about each tool by clicking on it.

microscope

magnifies objects to reveal features too small to see with the naked eye

trowel

scrapes soil with a flat, pointed blade

glue

bonds pieces of artifacts together without damaging them

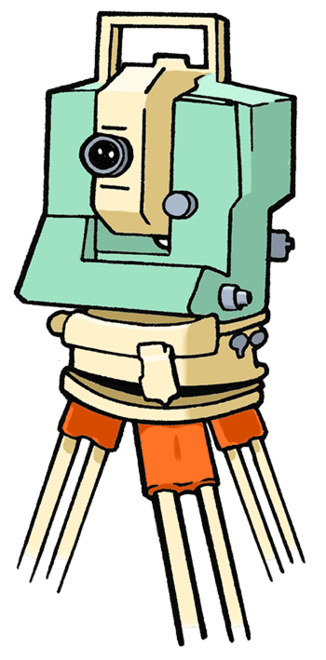

total station

measures the exact position of objects with a laser

expert

experts and local people help explain findings

sifter screen

captures small objects hidden in the soil

magnetometer

finds underground objects by picking up magnetic differences

THE PROBLEM: All we knew from the old maps was that there was a mission somewhere on the island, but we had no idea where. We spent three years surveying the 14,000-acre island. We narrowed down our search to an area the size of 25 football fields, still a huge area covered in dense forest.

What tool helped us find what's underground and gave us clues about where to excavate?

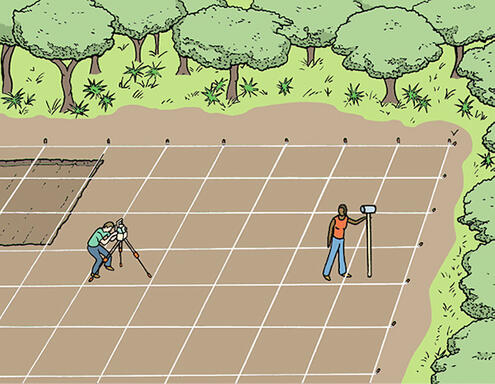

THE PROBLEM: After we found the church, we made a map of the site and decided where to dig. We divided the site into 1-by-1-meter grids. As we dug, we found lots of artifacts. But an artifact by itself only tells us part of the story We needed to know where it came from to understand how it was used.

What tool did we use to record the position and depth of each object?

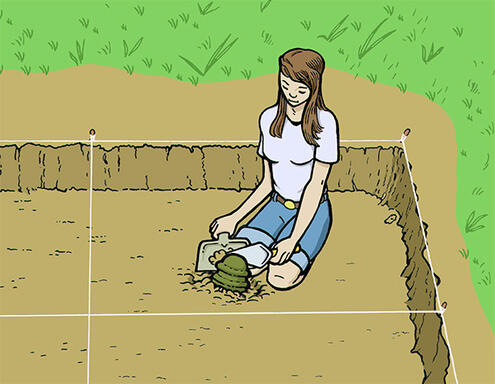

THE PROBLEM: Excavation is serious business. Every time we dig, we're destroying part of the site. I only get one chance to dig each spot, and it's my responsibility as an archaeologist to disturb the ground as little as possible. I also have to be careful not to damage delicate artifacts.

What tool helped me dig carefully without destroying evidence?

THE PROBLEM: Most of the time we can identify the artifacts we find. But some leave us stumped. One day while digging at the place where priests lived, we found a copper-lined basin in the shape of a pear. No one on our team knew what it was, so we preserved it in place and protected it for the future.

What would have helped us identify this artifact?

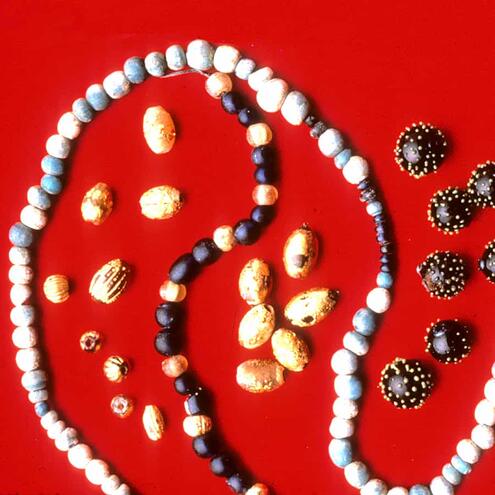

THE PROBLEM: We found all kinds of artifacts, including thousands of delicate beads buried deep in the dirt. We had to analyze each one to determine when they were made, where they were made, and what material they were made of. We knew this information could tell us a lot about the people who lived at the mission.

Which tool helped us closely examine the beads?

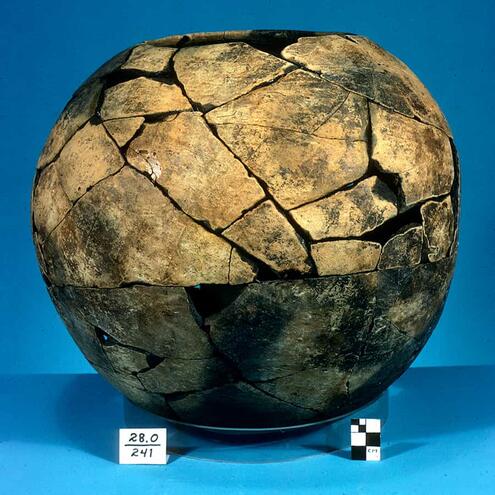

THE PROBLEM: Digging in the mission's kitchen, we found many ceramic pottery pieces.We recorded where each piece was found and gave it a number. Later, this information would tell us many things, like how the vessel broke. We can also learn a lot about how the pottery was used by looking at the vessel as a whole.

What tool helped us put the pieces together without damaging them?

We used a magnetometer to figure out where to excavate.

Start here

We used a total station to map the location of artifacts.

click here

A trowel helped us carefully scrape soil from fragile objects.

click here

A local priest helped us identify what a copper basin was used for.

click here

Using a microscope we could see what the beads were made of.

click here

We used glue to put the pieces of a vessel together without damaging it.

click here

drag correct tool here

THE PROBLEM: All we knew from the old maps was that there was a mission somewhere on the island, but we had no idea where. We spent three years surveying the 14,000-acre island. We narrowed down our search to an area the size of 25 football fields, still a huge area covered in dense forest.

What tool helped us find what's underground and gave us clues about where to excavate?

THE SOLUTION: We divided the area into a grid and walked along each section with a magnetometer. It picks up differences in the magnetic strengths of things underground, like burned walls. We found three big changes in the readings. We dug at each spot and found the mission church, the kitchen, and then the well. The magnetic changes around the church were strong because it had burned down.

There were trees and plants everywhere we looked.

We cleared part of the island’s dense forest to begin our dig.

THE PROBLEM: After we found the church, we made a map of the site and decided where to dig. We divided the site into 1-by-1-meter grids. As we dug, we found lots of artifacts. But an artifact by itself only tells us part of the story We needed to know where it came from to understand how it was used.

What tool did we use to record the position and depth of each object?

THE SOLUTION: A mapping tool called a total station shoots a laser that measures the depth and position of everything on a site. We used it to map the location of the artifacts we found. If we know where they came from, we can reassemble the site when we get back to the lab.

We used tape measures and strings to divide the site into grids.

Once the site was divided, we dug in an orderly way.

THE PROBLEM: Excavation is serious business. Every time we dig, we're destroying part of the site. I only get one chance to dig each spot, and it's my responsibility as an archaeologist to disturb the ground as little as possible. I also have to be careful not to damage delicate artifacts.

What tool helped me dig carefully without destroying evidence?

THE SOLUTION: I used a trowel because its flat blade helps me scrape the soil carefully and uncover fragile objects. Like most archaeologists, I use the sturdy Marshalltown trowel, which comes in different shapes and sizes. Some archaeologists personalize their trowels by wrapping the handles or even burning their initials into them.

Small tools like dental picks are perfect for fragile excavation.

We poured the dirt into a sifter to find smaller artifacts.

THE PROBLEM: Most of the time we can identify the artifacts we find. But some leave us stumped. One day while digging at the place where priests lived, we found a copper-lined basin in the shape of a pear. No one on our team knew what it was, so we preserved it in place and protected it for the future.

What would have helped us identify this artifact?

THE SOLUTION: Lucky for us, a Franciscan friar named Conrad joined the dig. He immediately recognized it as a foot font, or a basin for soaking feet. The priests that lived at the mission 300 years ago were called the Order of the Barefoot Friars. Not wearing shoes was part of their strict, solitary life. When they gathered together, they soaked their feet. Father Conrad was familiar with these customs.

Scientists, workers, and volunteers — each brought valuable skills.

Father Conrad was our expert on the history of the Franciscan friars.

THE PROBLEM: We found all kinds of artifacts, including thousands of delicate beads buried deep in the dirt. We had to analyze each one to determine when they were made, where they were made, and what material they were made of. We knew this information could tell us a lot about the people who lived at the mission.

Which tool helped us closely examine the beads?

THE SOLUTION: We used a microscope to classify the beads by material, color, shape, and size. Before the Spanish came, beads were made of shells and bones. When the Spanish arrived, they brought with them glass beads from Europe and Asia. So if we find beads made of glass, then we know that they're from thousands of miles away and were brought to the area by Europeans!

This is one of the beaded necklaces we discovered.

We were able to restring some of the beads into necklaces.

THE PROBLEM: Digging in the mission's kitchen, we found many ceramic pottery pieces.We recorded where each piece was found and gave it a number. Later, this information would tell us many things, like how the vessel broke. We can also learn a lot about how the pottery was used by looking at the vessel as a whole.

What tool helped us put the pieces together without damaging them?

THE SOLUTION: We used a special kind of glue to put pieces of this artifact together. This glue is not permanent, which lets us take the pieces apart again. We want to be able to reverse everything we do to an artifact. At the same time, we want to help preserve these objects so they're around for another 400 years.

Left: We excavated a medallion. Right: It was carefully cleaned.

A reconstructed artifact can give us more data about how it was used.

Image Credits:

All photos: courtesy of AMNH, David Hurst Thomas, and Lori Pendleton; Illustrations: Eric Hamilton

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water