Marine biology is the study of life in the ocean. This huge body of saltwater covers about two-thirds of our planet's surface and contains many different marine ecosystems. Life within it is more diverse than life on land!

What are the big ideas about marine biology?

1. The Ocean is Big and Constantly Moving

Our planet is made up of five great oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, and Southern. They're all linked together, creating a huge body of saltwater called the World Ocean. It surrounds continents and islands, covering more than 70% of Earth's surface.

This large body of water is always in motion. The pull of gravity from the Sun and the Moon creates tides that in turn create ocean currents. Currents shape our planet’s weather and climate by moving warm water from the tropics and cold water from the poles. And they move not only water, but also life within it, from giant jellyfish to tiny plankton.

Surface currents move warm water (red arrows) and cold water (blue arrows) around the globe.

2. The Ocean Has Many Different Ecosystems

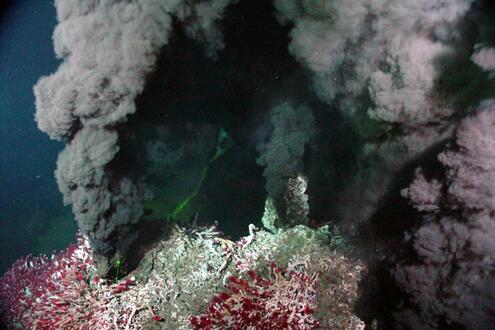

From above, the ocean may seem like one big, uniform mass of water . But look beneath the waves, and you’ll see tall mountains, deep trenches, and wide plateaux. These seascapes are formed over millions of years by geologic processes such as erosion, deposition, and plate tectonic forces .

Further from shore and deeper into the depths, conditions such as light, temperature, pressure, and salinity vary, giving rise to vastly different ecosystems, from coral reefs to polar seas to the sea floor. An ecosystem is a community of living things. Members survive by interacting with each other and with their environment. In fact, there are more kinds of ecosystems in the ocean than on land!

3. The Ocean Teems with Life

Many more organisms of different kinds live in the ocean than on land.

They glow, swim, swarm, squish, spout, wave, hide, drift, or pounce. As varied as life may be on dry land, the diversity of marine organisms is even greater. They range from gigantic whales to microscopic phytoplankton and everything between: jellyfish, sponges, sea dragons, marlins, giant squid, hatchet fish, seaweed, starfish, sea cucumbers, manatees, coelacanths, and stingrays, to name a few.

4. The Ocean Is Like a Layer Cake

In the ocean you see a much greater variety of life forms if you move up or down than if you move from side to side.

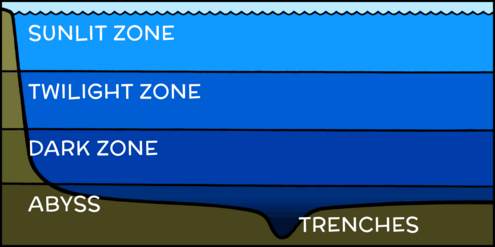

The ocean is a habitat that can be divided into different zones, or layers: sunlit zone, twilight zone, dark zone, abyss, and trenches.

The sunlit zone, near the top, is rich in life. Eighty percent of all marine organisms live near the shore. They live in ecosystems found along the continental shelves , such as coral reefs, mangroves, kelp forests, and estuaries. In these sunlit, shallow waters close to land, they find the conditions needed to support large quantities of life: food, light, and shelter.

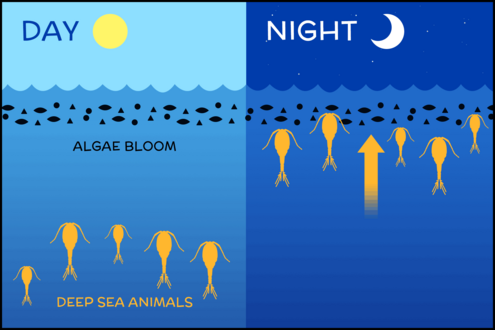

Billions of animals move up from the deep ocean to feed near the surface every night.

Algae, a group of photosynthetic organisms, also live in the sunlit zone. They contain green, brown, and red pigments that enable them to convert the Sun’s energy into food, providing huge quantities of food for the animals that live among them. Further out in the open ocean, large blooms of algae also provide food for the billions of deep-sea animals that rise to feed near the surface at night, and then return to the deep at dawn. This vertical migration is the largest mass movement of life on Earth. And it happens every night!

As you dive deeper and deeper down from the surface to twilight zone, less and less sunlight penetrates the water. It’s colder and darker here, and there's less life. The organisms that live here survive on zooplankton and sea snow , food that falls from above.

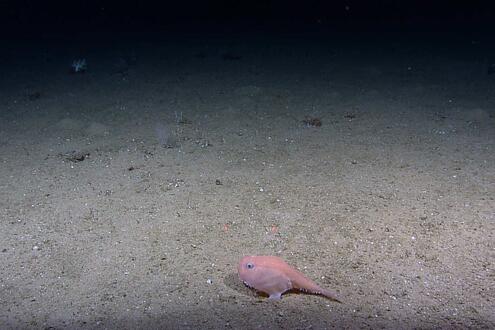

And way down deep is the dark zone, where signs of life are rare. Here, the pitch-black water is icy cold and its pressure is intense enough to crush a human. Some animals here have glowing lights on their bodies. This ability to generate light, called bioluminescence , helps them find food and mates.

5. Life Began in the Ocean

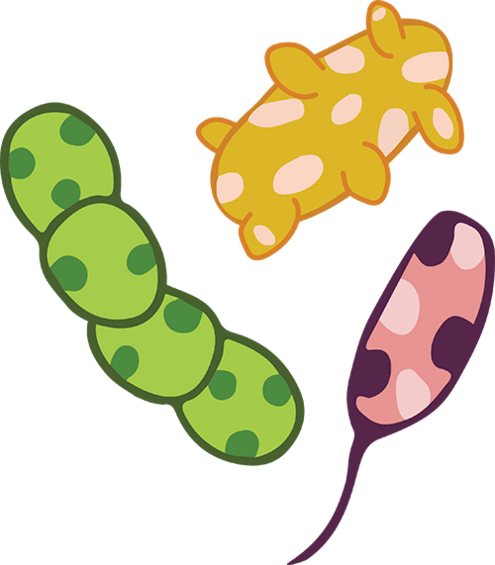

The first life on Earth was probably bacteria.

From studying fossils, scientists know that life on Earth probably started in the oceans about 3.5 billion years ago, soon after the oceans themselves formed.

The first life forms to appear were single-celled, microscopic marine organisms, followed by multicellular organisms. For most of Earth's history, life stayed in the oceans and thrived there. About 500 million years ago, some four-limbed marine vertebrates began adapting to life on land. Their descendants became the first land-dwelling vertebrates—and our ancestors! Many more millions of years later, a few types of land animals began adapting back to life in the ocean, and some of their descendants—such as dolphins and whales—now live in the ocean full time.

Some organisms, like the ancestors of these dolphins, adapted to life on land, but their descendants later returned to the ocean.

6. The Ocean is Full of Mysteries

Scientists know less about what's actually in the ocean than they know about the dark side of the Moon! Less than five percent of the ocean has been explored. And for every new species that we recognize, there may be hundreds more yet to be discovered.

But now, with scuba-diving gear, submersibles, satellites, and other technology, we can start to investigate parts of the ocean that were once beyond our reach.

7. Human Activity is Harming the Ocean

We've always depended on the ocean: mostly for food, but also for resources like oil, sand, and salt. Over the years, though, we've taken too much out of the ocean, and we've put too much in: pollutants like fertilizers, pesticides, plastic, motor oil, and trash.

It’s hard to comprehend that something as huge as the ocean can be fragile. But today, many marine species have been driven to the edge of extinction by overfishing and hunting. Development encroaches on our coastlines. Pollution stretches from shore to shore. And as we burn fossil fuels, we release carbon dioxide (CO2), which causes the atmosphere and oceans to warm. The gas also dissolves in water, making it more acidic; ocean CO2 levels are higher than they’ve been in 20 million years. These changes threaten many organisms and entire ecosystems.

How can we protect the ocean? We can understand more about it and the organisms that live there. People and governments can also work together to manage human impact.

What can you do? Go to "Be an Ocean Helper" to find out how you can take action and help the ocean!

Image Credits:

Sky and waves, ©Liz Vernon/AMNH; "What is Marine Biology?" Title, ©Liz Vernon/AMNH; Map of world's oceans and currents, ©AMNH; Coral reef, ©Wolfgang Poelzer/WaterFrame/AGE Fotostock; Mangrove forest, D. Convertini/CC BY-SA 2.0; Kelp Forest, Tiffany/CC BY-NC 2.0; Estuary, Jim Culp/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Polar sea, USGS; Sea floor, NOAA; Black smokers, NOAA; Humpback whale, Whit Welles/CC BY 3.0; Jellyfish, Tavis Beck on Unsplash; Sea sponge, Kirt L. Onthank/CC BY-SA 3.0; Seadragon, Richard Ling/Wikimedia Commons; Marlin, ©R. Dirscherl/AGE Fotostock; Hatchetfish, Francesco Costa/CC BY-SA 3.0 Seaweed, Toby Hudson/CC BY-SA 3.0; Starfish, ©Philippe Clement/AGE Fotostock; Sea cucumber, NOAA; Manatees, ©FWC Research; Coelacanth, ©Peter Scoones/Science Source Sting ray, David Clode on Unsplash; Sea turtle, ©Reinhard Dirscherl/AGE Fotostock; Monk seal, James Watt/US FWS; Spider crab, ©Cultura; Conch, ©Alex Mustard/NPL/Minden Pictures; Tube anemone, Paul Thompson/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; Ocean zones, ©Eric Hamilton/AMNH; Vertical migration graphic, ©AMNH; Bacteria, ©Brett Taranda/AMNH; Dolphins, NOAA; Submersible, ©Triton Submarines LLC; Gripper hand, ©AMNH; Divers with camera, ©Neil van Niekerk; Scientist tagging whale, ©Ari Friedlander; m-AUEs, ©Scripps Oceanography/UC San Diego; REMUS sonar device, ©Kelly Benoit-Bird.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water