The Poop Cure

Using Fecal Microbiota Transplantation to Fight Disease in the Gut

Your poop contains living beings! Most of it isn’t alive, of course—as you’d expect, a lot of it is made up of things like water, undigested food, and dead human cells. But more than half the dry weight of poop is bacteria. And the bacteria we flush down the toilet are only a small sample of the vast population inside us. These microbes play a vital role in our bodies—for example, producing vitamins, helping break down food, or keeping dangerous bacteria from growing out of control. Our health depends on their health.

What happens when something goes wrong with those invaluable inner companions? Physicians are increasingly turning to an exciting, if icky procedure: Fecal transplants. Yes, this is just what it sounds like. Doctors take somebody else’s poop—“thoroughly tested poop, for-sure healthy poop, just beautiful poop,” in the words of Ari Grinspan, Director of GI Microbial Therapeutics at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City—and place it in the patient’s colon. While fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) dates back at least to 4 th century China, its systematic use in the United States is more recent. In the 1980s doctors discovered that fecal transplants could effectively treat intestinal infections caused by the bacterium Clostridium difficile, and in 2013 the FDA classified fecal matter as a drug.

Animation by Ramin Rahni @lunarpapacy

Our bodies are also home to more than 10 trillion bacteria, maybe even outnumbering our own cells. They live everywhere: in our mouths, our armpits, our ears; on our genitals, our fingertips, our shoulder blades. Each area of our bodies shelters a distinct community, with its own distinct assortment of species and strains.

Some 10 trillion of these microbes make their home in the intestinal tract, almost all in the large intestine, also called the colon. And this community is enormously diverse; in fact, diversity may be the most important factor for a healthy gut microbiota, says Grinspan. Healthy humans play host to some 150 to 250 species of gut bacteria (also called gut flora or intestinal microbiota), but while we all harbor subsets of the same group of species, the particular species and strains can vary dramatically from person to person.

Mom and Poop

Grinspan was the first person to perform a fecal transplant at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. The youngest of three boys, he was born by caesarian section in 1982 in Connecticut, where he was breastfed and enjoyed the company of the family pet, a golden retriever. All these facts about him set his gut flora apart from those of someone with a different life history: a formula-fed Wisconsin dairy farmer, say, or a Mumbai accountant who was born vaginally. A baby’s first exposure to these bacteria depends on its mode of birth: whether the microbes come from the mother’s birth canal, or her skin. “They go into your nose and mouth, and you swallow them,” Grinspan says. All sorts of experiences play a role in establishing these microbes, from what the baby eats to where it lives to whether it’s given antibiotics for an infection. “If you had sisters or brothers who beat you up or spit at you—like I did—that will also have an effect on your microbiota,” says Grinspan.

After we’ve reached around the age of three, the microbes have established themselves thoroughly in our intestinal tract. We can alter their makeup somewhat by changing our circumstances: traveling to another continent, or just another neighborhood; taking up horseback riding; moving in with a new partner. But even dramatic changes will only alter our gut flora by about 50 percent, says Grinspan, and if our circumstances change back, usually our microbes will change back too.

These bacteria are not just freeloading passengers, but key partners in our health. Humans and our gut flora evolved together in an intimate, still-mysterious relationship. Some gut bacteria produce vitamins our bodies can’t make, such as folic acid. Some break down fiber into simple, digestible sugars and short-chain fatty acids, which not only give us energy, but also act as important messengers, signaling to other bacteria and to our own cells. Along with our intestinal cells, the microbes make up a complex community called the microbiome, which Grinspan defines as the total of the gut bacteria (microbiota) and their habitat, including their interactions with their host. “The microbiota make all sorts of enzymes and signals and neurotransmitters that can interact with the human cells that line the colon,” he says.“There’s all this crosstalk that we’re really just beginning to understand.” Our microbiota can call for inflammation, or tell us to tamp it down. They can warn us if there’s a pathogen in our gut, alerting our immune system to prepare for a fight. Scientists have found associations between the gut microbiome and conditions as varied as infections, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, and inflammatory bowel disease—and even neuropsychiatric issues such as autism and depression.

In the 20 th century medical science introduced a new threat to the busy metropolis of the microbiome: antibiotics. These wonder drugs allow doctors to save patients from bacterial infections that in previous centuries often meant death. Since antibiotics don’t distinguish between pathogens and helpful bacteria, however, the microbiota pay the price.

Take a course of antibiotics, and you’ll play havoc with your gut flora. Many will survive the knock-out punch, says Grinspan, and your microbiome will generally return to normal within a week or two. A healthy, diverse community of good bacteria helps keeps pathogens at bay; until your microbiome comes back, the ravaged city of your colon is at risk of being invaded by Clostridium difficile, or C. diff.

This pathogen, the most frequent cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea, can give rise to symptoms ranging from fever, nausea, agonizing stomachaches, diarrhea, and dehydration, all the way to death. It’s especially common in places like hospitals and nursing homes, where many people with weakened immune systems are housed at close quarters and are taking antibiotics. C. difficile is difficult to get rid of.

Antibiotics can often control it, but not for long. Twenty percent of patients treated with antibiotics have a recurrence within days to weeks after their first treatment; 40 percent will recur after a second treatment, and 60 percent after a third treatment. So when a landmark article was published in January 2013 showing that for recurrent C. diff infections, fecal transplants beat the standard of care (treatment with the antibiotic vancomycin) by a whopping 60 percent, gastroenterologists were excited. Ninety percent of patients with recurrent C. diff got better after a fecal transplant, compared to 30 percent after the antibiotic. Grinspan had heard anecdotes about these cures in the early 2000s, as a medical student. He says, “I thought, this is incredible stuff!”

Fecal Attraction

Grinspan traces his interest in poop to childhood. “Growing up the youngest of three brothers, it was poop jokes galore,” he says. His father, a doctor, shared the boys’ humor (which his mother, a high school English teacher, tried in vain to rein in). “The GI tract always sort of spoke to me,” says Grinspan. “I was always fascinated with how this very important organ functioned—and, more importantly, what happened when things went wrong.”

Fittingly, at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, Grinspan was drawn to gastroenterology. He started working with Lawrence Brandt, one of the pioneers in the field of fecal transplant. “It was through Dr. Brandt that I began to see how important, how novel, and how monumental a discovery fecal transplant is,” says Grinspan. After residency, he did a GI fellowship at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. At the time, the hospital had no fecal transplantation program—but like all hospitals, it had its share of C. diff. Grinspan wanted to offer his patients this effective treatment.

First he had to get approval, including from the hospital’s biosafety officer. As Grinspan recalls, “The biosafety officer said, ‘Okay, so what you’re going to do is—tell me if I’m right—you’re going to take somebody’s stool. You’re going to put water into it and shake it.’ I said, ‘That’s right—I’m going to make the world’s dirtiest martini. Then I'm going to put the dirty martini into somebody’s colon.’ He says, ‘Okay, the drug itself doesn’t bother me. Neither does the administration. But the shaking part is a problem. You’re shaking [feces], so you’re going to aerosolize some of it. You’ll have to go to a lab that has an air ventilation system and shake it underneath the hood, because you don’t want those particles to go all over the place. It’s a biosafety hazard level 2.’ And I said to him, ‘So let me get this straight. If I’m in the lobby of Mount Sinai and there’s hundreds of people around and I fart, do you have to clear the lobby? What—should we quarantine?’ And he looked at me, and he laughed. He says, ‘Very funny. But you still have to shake it under the hood.’”

Once Grinspan had the hospital’s approval to perform a fecal transplant, he needed to convince his first patient, a woman with a stubborn C. diff infection. “She was in and out of the hospital, with very compromised quality of life. I said, look, you’ve had this infection like eight times in this year alone. We don’t have another antibiotic concoction that you haven’t already tried. You have exhausted all of the standard options. It’s time to try something different.”

At the time—2012—most members of the public, and even most doctors, had never heard of fecal transplants. Grinspan spent hours talking to the patient before he overcame her “very strong ick factor.” Then they had to identify a stool donor. In his early days performing fecal transplants, Grinspan asked his patients to select their own donors, picking a healthy person with whom they felt comfortable having this strangely intimate interaction. He tested both the poop and the donors themselves for dozens of pathogens and conditions, eliminating anyone with infections such as hepatitis and HIV, or with medical conditions—including heart disease, diabetes, and liver disease—which have been associated with changes in the microbiome. To be safe, he excluded anyone with any significant family history of conditions that could potentially be transmitted.

These days, because the process of screening donors and their poop is time-consuming and expensive, Grinspan rarely uses individual donors. Instead, he relies on a large, nonprofit stool bank. “It turns out frozen poop is just as good as the fresh stuff, so they can collect a lot of it and freeze it,” says Grinspan. In 2012, though, Grinspan had not yet started to use a stool bank, and his first patient chose a close friend to be her donor.

Inside the Endoscopy Suite with Ari Grinspan

Grinspan performed his first fecal transplant on a patient with a severe, recurring C. diff infection. The very next day, her infection was gone. “It’s been six years now, and she hasn’t had any episode of C. diff. Before the fecal transplant, she didn’t have a semblance of her life. And we cured her.”

That first year, Grinspan and his colleagues at Mount Sinai treated four C. diff patients with fecal transplants. The next year they treated about 20, and the next year about 50. Now they perform between 50 and 80 a year. Nine out of 10 of these transplants succeed at once; when the procedure fails to cure an infection the first time, they try again, with an overall success rate of 90 percent.

Internal Mysteries

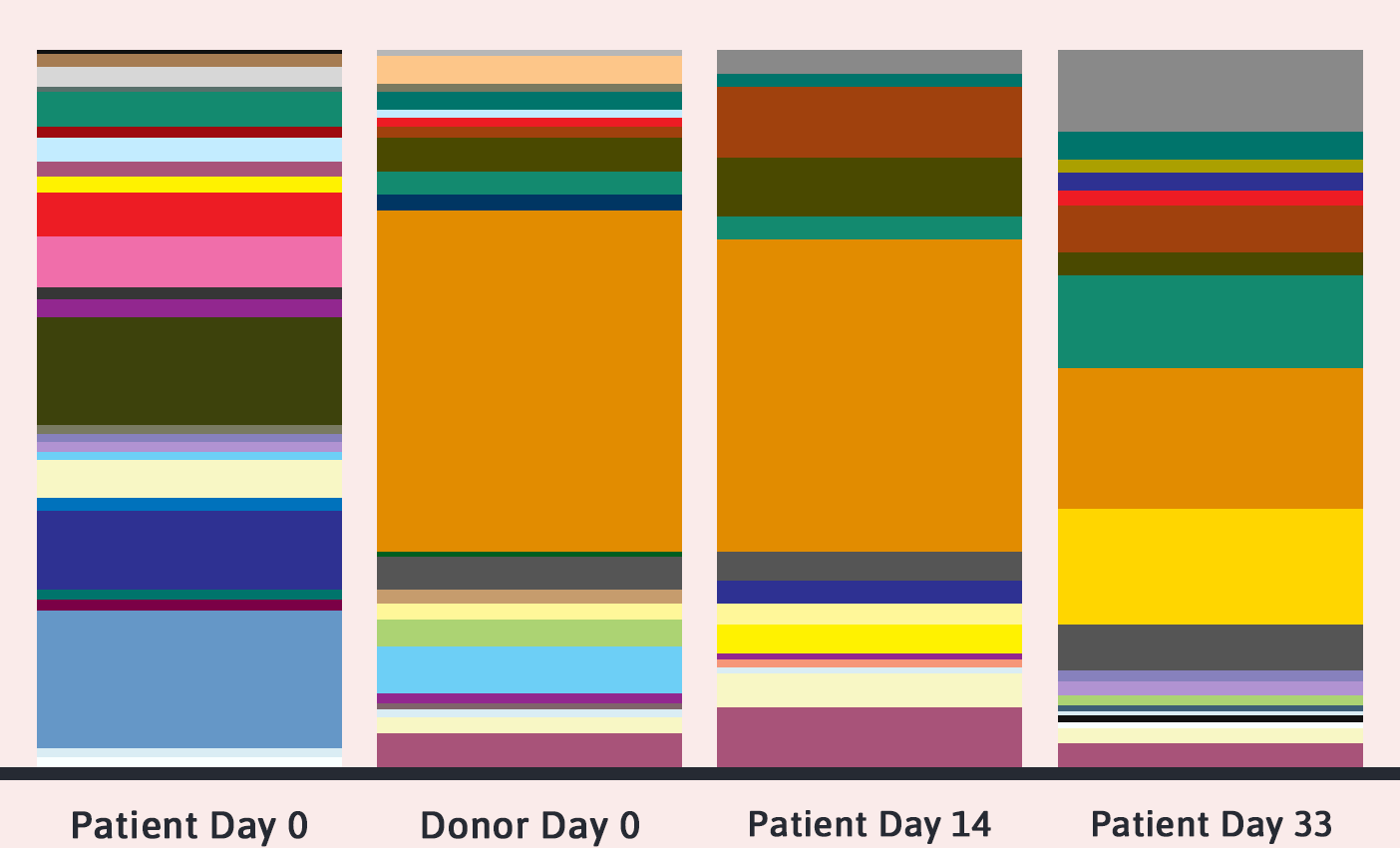

Immediately after a fecal transplant, a patient’s microbiota look very similar to those of their donor, as you’d expect. But inspect them again in a few weeks, and the balance of bacteria will likely start to look quite different. Will these patients’ gut flora eventually return to their original state, as most people’s do sooner or later after a disruption? “That’s something we don’t know, because we don’t know what their microbiota looked like before we did the transplant,” says Grinspan.

In fact, how fecal transplants work at all is still something of a mystery. The prevailing theory is that the addition of healthy microbiota overcomes the pathogens that are making the patient sick. And that may, in fact, be the answer—or at least part of it.

But recent research hints that something else may be going on as well, or perhaps even instead. In one small study, some patients recovered from C. diff infections after receiving transplants of sterilized poop, which contained no living bacteria. In another, transplants of the patients’ own poop did the trick for some people. Is some fecal element other than bacteria responsible for the cure? Grinspan’s prescription: More research.

So far, the FDA has approved fecal transplants only for C. diff, but human trials are currently in progress to see whether it helps with inflammatory bowel disease, both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; irritable bowel syndrome; obesity; and fatty liver disease, among other conditions. Researchers are also beginning to consider whether fecal transplants might help patients who have conditions associated with altered microbiomes, such as autism, multiple sclerosis, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, alopecia (an autoimmune condition that causes hair loss), and bacterial infections other than C. diff. But these uses, if they pan out at all, are still far in the future.

No matter how much you’re tempted, Grinspan cautions, “Don’t try this at home.” Leave fecal transplants to the professionals. Do people actually try to self-administer fecal transplants? “You’d be surprised,” he says. Meanwhile, the best way to keep your microbiota happy is to eat lots of fiber. “Fruits, vegetables, beans, whole grains—it all feeds the flora,” says Grinspan, who started the morning with a grapefruit. When your microbiota are healthy, chances are much better you will be too.

—by Polly Shulman

The Power of Poop

Watch Dr. Grinspan talk about FMT at the January 2018 SciCafe.