Some volcanoes explode with the force of an atomic bomb. Others spill rivers of gently flowing lava.

What causes volcanoes to erupt? How do scientists study them? Let’s explore one of the most powerful, destructive volcanic eruptions in history.

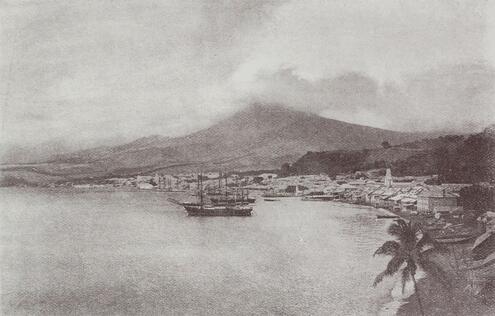

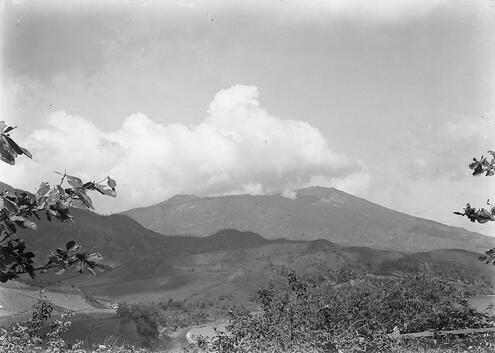

The city of St. Pierre with Mt. Pelée in the distance.

More than a century ago, the city of Saint-Pierre was known as the Paris of the Caribbean. Located on the island of Martinique, Saint-Pierre was a center of trade in rum, sugar, cocoa, and coffee. Its boulevards were lined with beautiful homes and shops.

But in the spring of 1902, all of that changed…

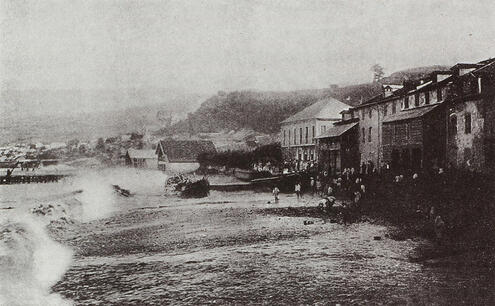

On the morning of May 8, the nearby volcano Mt. Pelée exploded in a burst. A swirling cloud of hot gas, ash, and rocks, called a pyroclastic flow, rushed down the mountainside at 480 kilometers per hour (300 mph). It burned everything in its path, including the town of Saint-Pierre and nearly all the ships in the harbor. Within two minutes, close to 30,000 people were dead.

See a pyroclastic flow in action.

At the time, people living on these islands underestimated the risks of living near the volcanoes. They had ignored signals that the volcanoes were still active.

April 23

Earthquakes shake dishes from shelves in Saint-Pierre.

April 24

Fine ash from Mt. Pelée falls for two hours on a town nearby.

May 2

A column of ash and fumes rises nearly 3 kilometers (2 miles) above the mountain. An inch of ash covers Saint-Pierre.

May 5

A mudflow from Mt. Pelée kills 23 people north of the city. Fifteen minutes later, a small tsunami reaches Saint-Pierre.

May 6

Mt. Pelée spews columns of gas and ash, and flings huge molten rocks in the air.

May 7

Mt. Soufrière, a volcano 120 kilometers (75 miles) north on the island of St. Vincent, erupts, and a boiling mudflow of steam and ash kill 1,565 people.

May 8

Mt. Pelée explodes, destroying the town of Saint-Pierre.

May 20

A second eruption covers the now desolate town of Saint-Pierre.

May 31

The volcano’s dome rises nearly 300 meters (1,000 feet). A spine, called the “Needle of Pelée,” juts above it. Within a couple of months, the needle collapses.

News of the disaster horrified the world. Geologists were drawn to Martinique to understand the science behind the tragedy. The American Museum of Natural History sent geologist Edmund Hovey.

Take a look at what Edmund Hovey saw and collected.

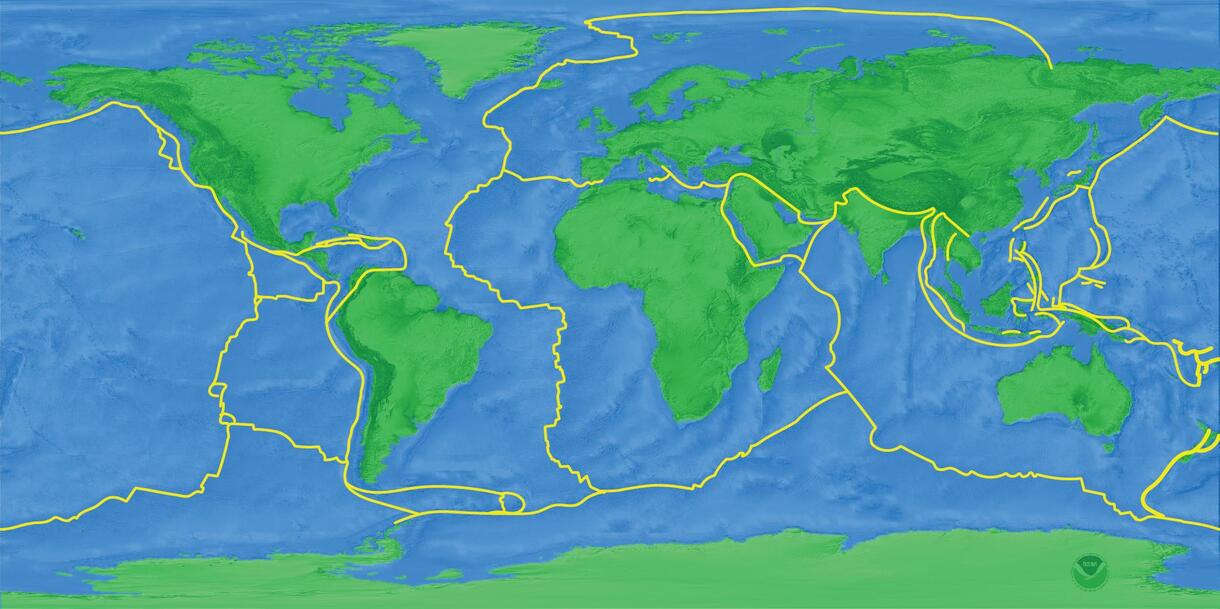

Earth’s crust, or outer shell, is broken into big pieces called tectonic plates. These plates fit together like a puzzle. They are moving very slowly all the time, as slow as fingernails grow! When the edges of the plates meet, plates can collide, separate, or grind against each other.

Drag the slider to reveal tectonic plate boundaries.

Nearly every Carribean island has its own active volcano. That’s because these islands lie above subduction zones, where one tectontic plate sinks, or subducts, beneath another.

Find out how subduction causes volcanoes to form.

- When an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, it sinks into the mantle below.

- As the oceanic plate sinks, fluid (shown in purple) is squeezed out of it.

- The fluid flows up into the mantle rock above and changes its chemistry, causing it to melt. This forms magma (molten rock).

- The magma rises and collects in chambers within the crust.

- As magma fills the chamber, pressure grows. If the pressure gets high enough, the magma can break through the crust and spew out in a volcanic eruption. Most explosive volcanoes occur above subduction zones.

It’s all a matter of chemistry. The way a volcano erupts depends on the amount of gas and silica (a molecule of silicon oxygen) in the magma below. Magma with lots of silica is thick and gooey, while magma low in silica is thin and runny. And in magma with lots of gas, bubbles form as it rises. The more bubbles that form, the more explosive the eruption!

Mt. Pelée was the most explosive type of volcano: it was high in silica and high in gas. This type of volcano is called a stratovolcano.

Explore how different shapes of volcanoes have different kinds of eruptions.

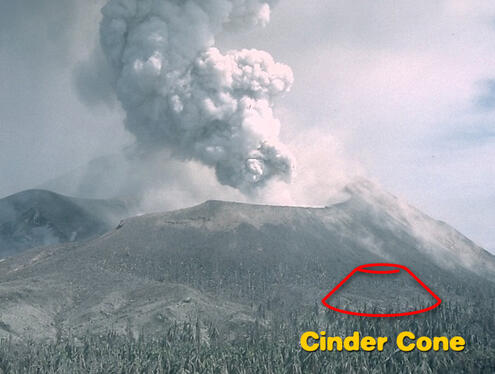

The most explosive eruptions come from stratovolcanoes, like the Augustine Volcano in Alaska. When they erupt, stratovolcanoes blow huge columns of gas and ash into the air that can collapse in hot, fast-moving clouds called pyroclastic flows.

A shield volcano, like Mauna Kea in Hawaii, has gentle slopes formed by oozing, runny lava. The magma is low in silica and low in gas, so it doesn’t erupt explosively.

A lava dome, like the one of Chaitén Volcano in Chile, forms when thick lava oozes from a vent, piles up, and cools into a steep mound. The lava is thick because it’s high in silica, and it oozes instead of explodes because it’s low in gas. Sometimes lava domes form after explosive eruptions.

A cinder cone volcano, like Tavurvur in Papua New Guinea, forms when erupted fragments harden and fall to the ground, accumulating around the vent in a cone shape. The lava is low in silica, so the lava is runny. High gas levels make for the explosive eruptions that send it flying. Cinder cones typically form at the beginning of eruptions, and lava flow follows.

Around the world, there are about 1,500 active volcanoes. Active volcanoes are those that have erupted in the past, and could erupt again. About twenty are probably erupting right now.

These days, eruptions rarely come as a surprise. Scientists are keeping a watchful eye on active volcanoes. They want to find out if magma is rising beneath a volcano — a sign that it could erupt. The goal? Reduce the risk to humans who live near them.

Check out some of the tools that scientists use to monitor volcanoes.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water