Click the ( + ) signs to explore the items in our scrapbook.

The first step in fossil hunting is finding an area that might be loaded with fossils. Paleontologists often start hunting with binoculars, looking for rocks that have the right color and texture, such as red sandstone cliffs.

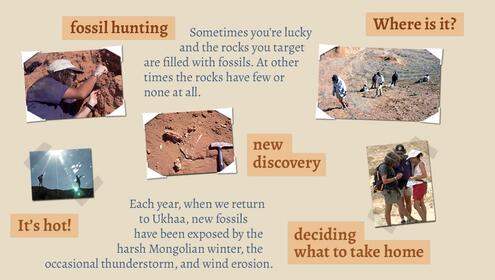

fossil hunting

Fossil hunting can be tedious and exhausting. It can be hot and uncomfortable. You might not have enough water, and there may be flies around. There are so many good reasons to quit. Sometimes you’re lucky and the rocks you target are filled with fossils. At other times the rocks have few fossils or none at all.

Where is it?

Collecting fossils involves staring at the ground for hours … and hours … and hours. The team members have found that the more time they spend looking for fossils in the Gobi, the better they become at finding them.

It's hot!

Given the blazing heat, one of the greatest dangers facing paleontologists in the desert is dehydration. What might seem like a leisurely walk down a canyon can become dangerous if one gets caught without enough water to drink.

a new discovery

On a typical day, a lucky paleontologist might find 20 small specimens encased in chunks of rock. More often than not, the identity of the fossils isn’t known until the specimen is cleaned and prepared back at the Museum. Sometimes the finds are better than the scientists imagined; other times, they’re a big disappointment.

deciding what to take home

Paleontologists are very picky about which fossils they jacket and take home, especially the large ones. We only have the time and resources to collect one medium-size dinosaur a year. This means that unless a dinosaur can help answer some pressing research question, it will usually stay in the sandstone.

Image Credits:

All photos, courtesy Discovery Channel Online

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water