Hi, I’m Bruno, and I’m at the American Museum of Natural History. Today I’m in the fossil halls to interview a titanosaur (tie-TAN-o-SAWR). It’s one of the largest dinosaurs ever discovered!

Let’s find out how this dinosaur lived millions of years ago, how it came to the Museum, and what it’s like to be one of the biggest members of the collection.

Bruno: Hello! What a thrill to meet you! I hear you’re the new official greeter of the Museum’s fossil halls. How does it feel to be the star of the show?

Titanosaur: Oh, I’m not the star at all. Have you seen the other fossils and casts in there? There’s a Tyrannosaurus rex , a flying reptile called a pterosaur , and an ancient shark relative, just to name a few. To be honest, I’m here because I didn’t fit in any of the smaller galleries!

Bruno: So, how big are you exactly?

Titanosaur: Well, I’m 122 feet long—longer than three big school buses. That’s also a little longer than this room, which is why my head and neck stick out the door.

Bruno: And what are you exactly? You look like a skeleton. Are those your real bones?

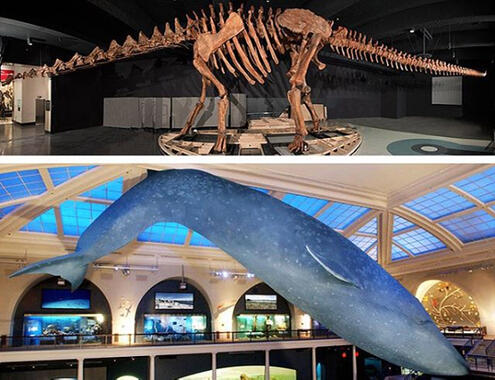

Titanosaur: Nope! In fact, they’re not even the fossils of my bones. After all, fossils are made of rock, so those would be way too heavy to mount. What you see here is a cast of my skeleton. My "bones" are exact copies of the ones that paleontologists found. They’re made of lightweight fiberglass.

Bruno: By the size of your cast, I imagine you’re based on the largest dinosaur ever.

Titanosaur: It’s true that I was one of the largest, but I actually wasn’t the largest dinosaur ever discovered. That title belongs to a different titanosaur.

Bruno: Well, you’re the largest animal in this Museum, that’s for sure!

Titanosaur: I’m definitely the longest! My new friend the blue whale in the Milstein Hall of Ocean Life was actually more massive in real life. She was modeled after a whale that weighed more than 100 tons—that’s heavier than 15 African elephants! I would’ve weighed around 70 tons. That’s only the same as about 10 African elephants.

Bruno: Do you get lonely out here, separated from the other dinosaurs?

Titanosaur: Not at all! Out here, I get to greet visitors to the fossil halls. And I get to be their first stop in their exploration of more than 600 fossils representing millions of years of life on Earth . That’s the best job in the Museum, if you ask me.

Bruno: Whoa, there are over 600 fossils on this floor? How do you keep them straight? And where do you even begin?

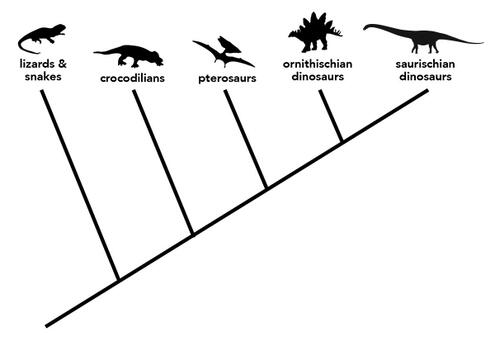

Titanosaur: It’s pretty simple if you know what you’re looking at. The hall is arranged like a giant “family tree.”

Bruno: Um, did you say “family tree”? You mean, all the fossils in these halls are related?

Titanosaur: You got it! All organisms—living and extinct, even you and I—are related. We all have a common ancestor. Scientists have made this family tree, or cladogram , to show how all living things are related. The closer organisms are on the tree, the more closely they are related—that is, the more they have in common. For example, saurischian dinosaurs like me are more closely related to ornithischian dinosaurs like Stegosaurus than to pterosaur .

Bruno: But how do scientists figure out these relationships?

Titanosaur: They organize living things by unique characteristics. For example, dinosaurs (like me!) have a hole in the hip socket. Scientists also use genetic information to determine how organisms are alike and different.

Image Credits:

illustrations of Bruno and titanosaur, Ebony Glenn; illustration of saurapod parade, ©Raúl Martin; excavation, ©Dr. Alejandro Otero; titanosaur modeling and installation, ©AMNH/D.Finnin; all other illustrations and photos, ©AMNH.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity

Brain

Brain

Genetics

Genetics

Marine BiOLogy

Marine BiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

MicrobiOLogy

PaleontOLogy

PaleontOLogy

ZoOLogy

ZoOLogy

AnthropOLogy

AnthropOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

ArchaeOLogy

Astronomy

Astronomy

Climate Change

Climate Change

Earth

Earth

Physics

Physics

Water

Water