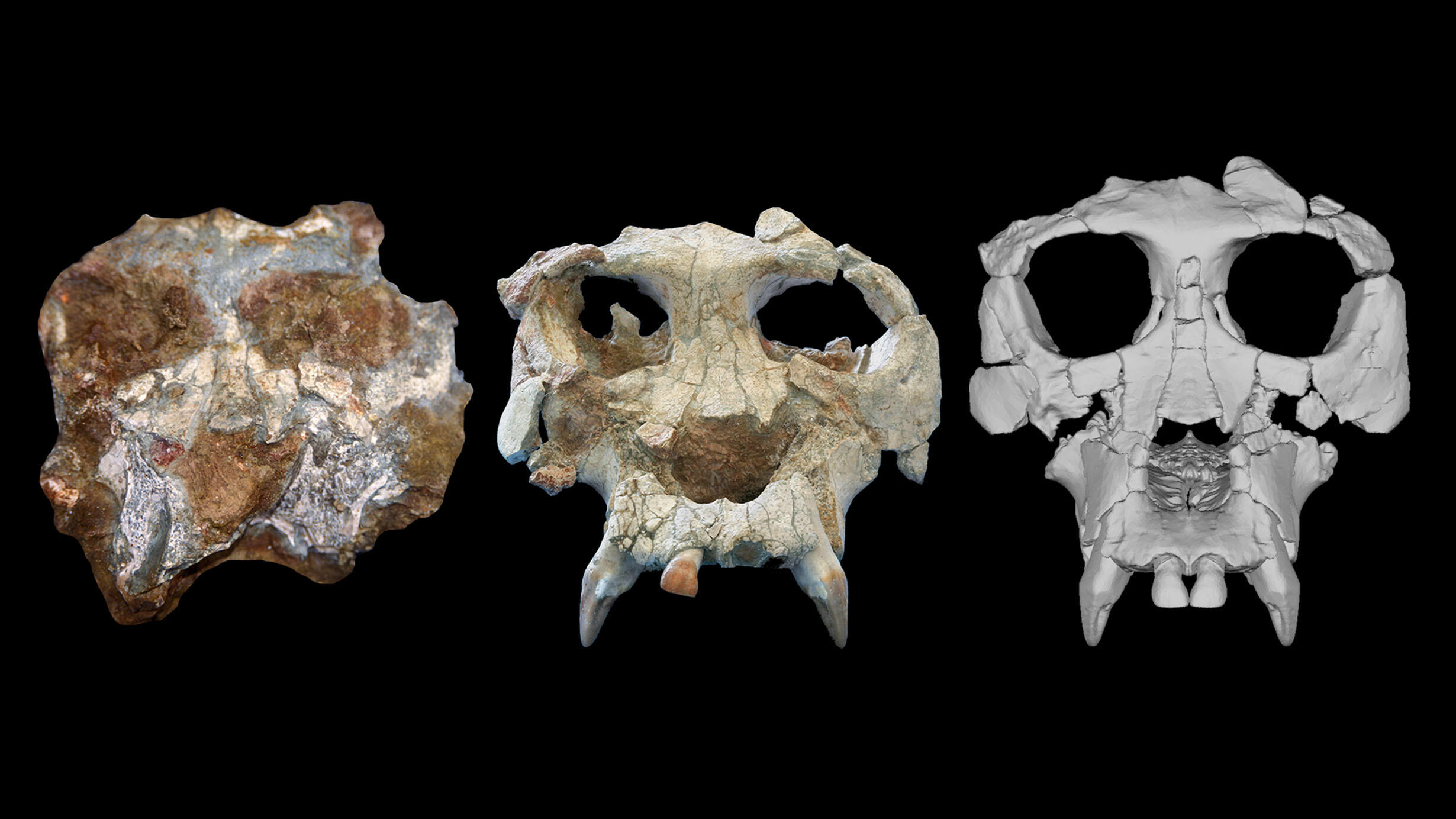

From left, the Pierolapithecus cranium shortly after discovery, after initial preparation, and after virtual reconstruction.

From left, the Pierolapithecus cranium shortly after discovery, after initial preparation, and after virtual reconstruction.Compared to most fossil finds—generally just small pieces—the 12-million-year-old fossils of the great ape species Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, are extraordinary: they include a well-reserved skull and a partial skeleton. Still, despite the species being first described nearly 20 years ago, debate about the ape’s place in the evolutionary tree has persisted, in part because its cranium was damaged and missing key features.

“One of the persistent issues in studies of ape and human evolution is that the fossil record is fragmentary, and many specimens are incompletely preserved and distorted,” said Ashley Hammond, associate curator and chair of the Museum’s Division of Anthropology. “This makes it difficult to reach a consensus on the evolutionary relationships of key fossil apes that are essential to understanding ape and human evolution.”

A new study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences aims to solidify the evolutionary spot of by Pierolapithecus by giving the ancient ape a facelift, using CT scans to virtually reconstruct the cranium and finding support for the species’ placement as one of the earliest members of the great apes and human family.

Hammond, along with other Museum researchers and colleagues at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology Miquel Crusafont in Spain, where the fossil is housed, found that Pierolapithecus is similar in overall face shape and size with both fossilized and living great apes. It also has distinct features not found in other apes from the same time period.

“Features of the skull and teeth are extremely important in resolving the evolutionary relationships of fossil species, and when we find this material in association with bones of the rest of the skeleton, it gives us the opportunity to not only accurately place the species on the hominid family tree, but also to learn more about the biology of the animal in terms of, for example, how it was moving around its environment,” said study lead author Kelsey Pugh, a research associate in the Museum’s Division of Anthropology and a lecturer at Brooklyn College.

First described in 2004, Pierolapithecus was one of a diverse group of now-extinct ape species that lived in Europe around 15 to 7 million years ago. Previous study of the species suggests that its upright body plan preceded adaptations that allowed hominids to hang from tree branches and move among them.