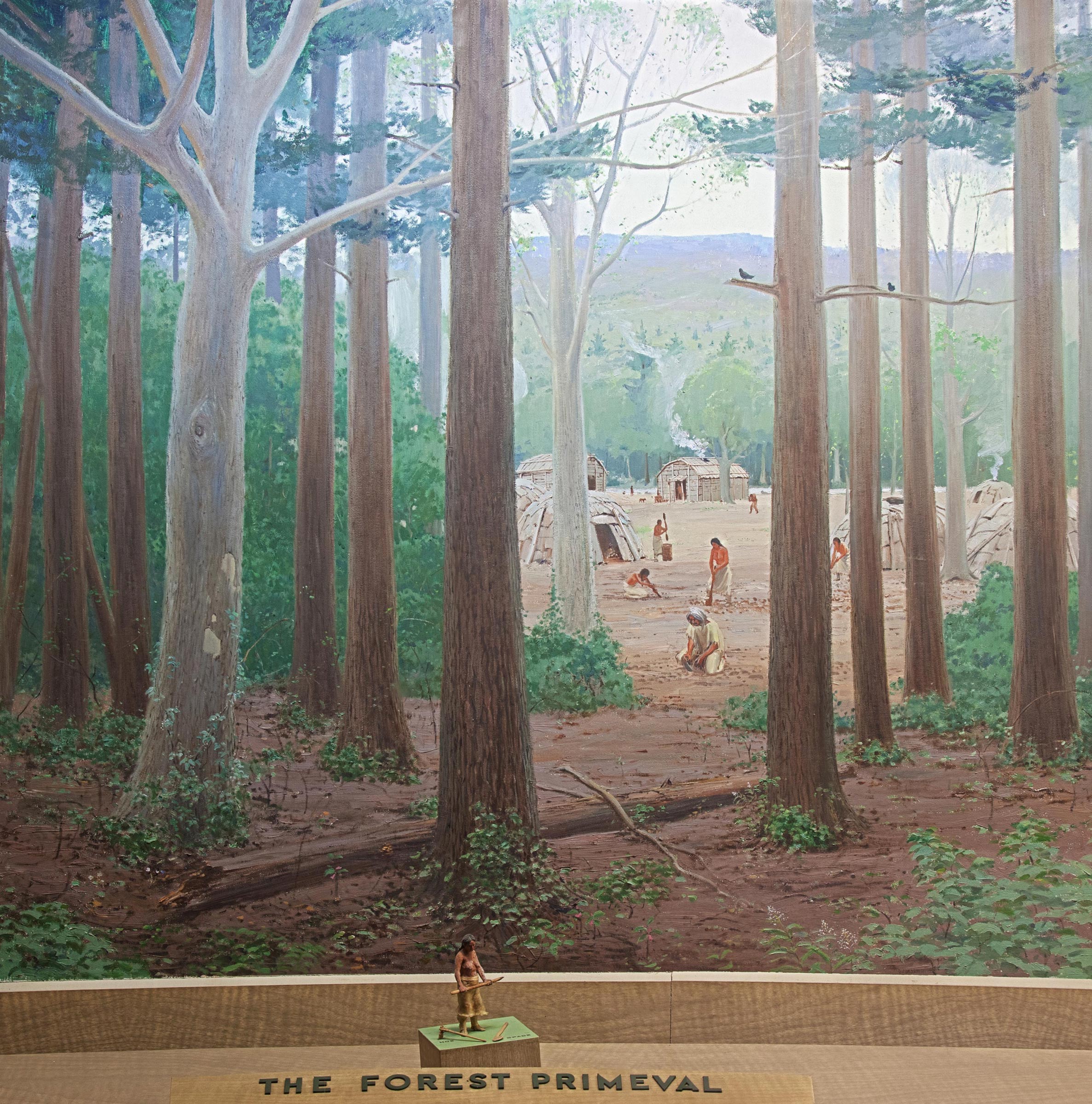

The Forest Primeval

In the course of thousands of years after the end of the Ice Age, a mature forest developed that covered great areas of northeastern United States. In this primeval forest the various forms of life achieved a kind of balance with each other and with the environment. As our forest do today, these primeval forests also varied according to the kind at underlying rooks, but pines (both white and pitch) probably dominated the landscape. White pines were known to reach a height at 250 feet and a diameter at 7 feet. Large oaks, maples, hickories and black walnut were also common.

When the Algonquin Indian invaded this forest, he did little to alter the conditions of nature. He lived off the natural plant and animal life without disturbing its basic character. He made small clearings where he built his villages and staked out his garden, only to abandon them again to the growth of the forest as he pursued his nomadic life.

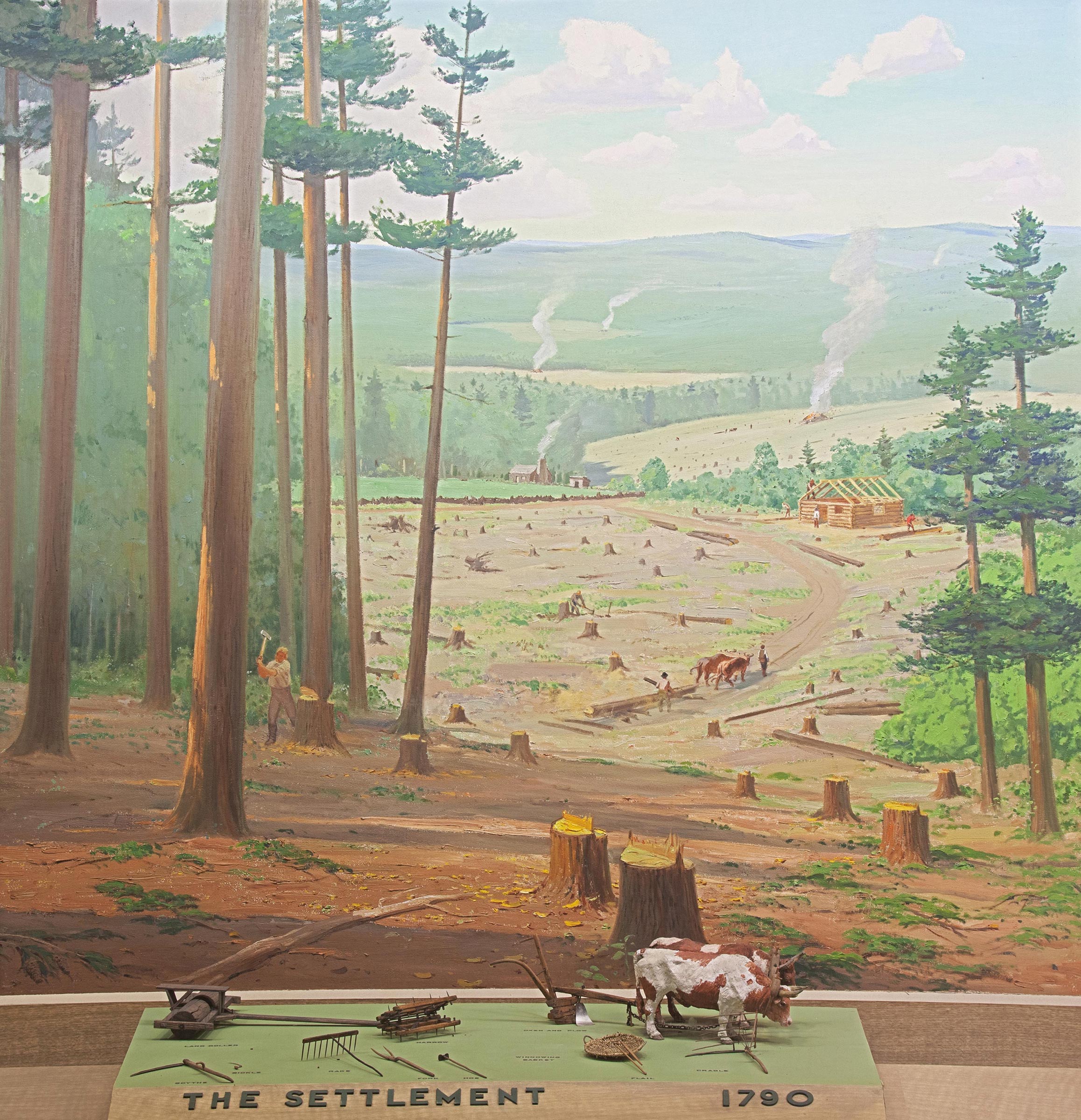

The Settlement 1790

The early farmer used hard, tough woods for their relatively simple tools. The plow, introduced from Europe, was sometimes tipped with metal to protect its point, and its sides were just beginning to develop a curve designed to turn the soil more efficiently. The crops introduced by the white man required more preparation of the soil than the Indian found necessary. The harrow, therefore, was employed to break the clods, and the roller to even the seed bed. Harvesting required the sickly to out the wheat, the rake to gather it, the fall to detach the kernel from the stalk, and the winnowing basket to segregate it from the chaff.

The early settlers depended upon animal power, particularly the oxen.

Long after New York City had been established and the coastal settlements from New England to Florida had become flourishing centers of colonial life, the hinterland remained undisturbed. A vast untouched wilderness stretched both east and west from the trading villages along the Hudson River. Toward the end of the 18th century the flood of settlement began to reach into every corner of Dutchess County. Dutch families from the older river communities, English from the Connecticut hills, and newer immigrants fresh from Europe staked out their farms. Eager for land to cultivate, and inexperienced with the fertility of the various soils of the forests, they cut down everything before them. Steep slopes, ledges, rich bottom land, thin soil and deep loam were indiscriminately exposed to the elements.

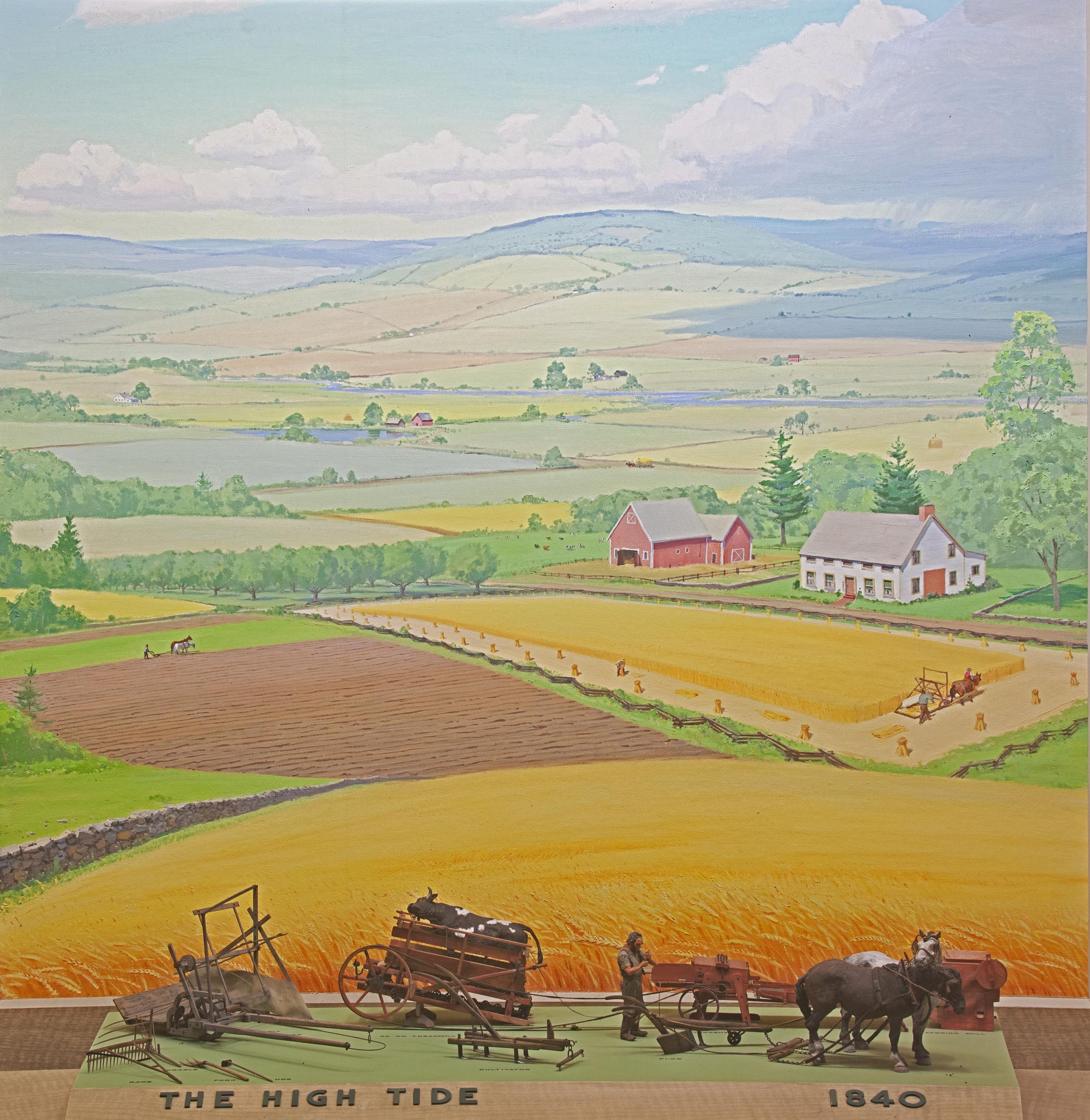

Hightide 1840

By the middle of the 19th century, little change had occurred in farming tools. The plow had developed further. Cultivators had been introduced to replace the laborious use of the hoe. A large horse-drawn rake lightened the chore of hand raking. And improved methods of reading were beginning to appear.

Horse power was gradually replacing the power of oxen.

During the course of thousands of years of undisturbed growth, the forests had gradually built a fertile layer of humus that covered both good and poor soils. Because of this humus the early farmers grew good crops even of the poorer soils and in unfavorable locations. They extended their fields wherever possible and the forest shrank to isolated spots where crops could not be grown. During this period, wheat, flax, and fruits were among the principal crops.

Agriculture as a settled way of life has a history of about 10,000 years. During most of that time tools and methods evolved very slowly until the new inventions of the industrial age began to make rapid changes both in the tools and the sources of power used in farming. The increasing specialization and efficiency of tools and of power are illustrated in our American experience by this sequence of exhibits.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the American Indian produced a primitive form of agriculture. Their principal crops, corn, beans and pumpkin, required little or no equipment for their harvesting. The earth was turned in preparation for planting by a simple digging stick which was practically all the equipment used. Power was exclusively human. Among the Algonquin Indians, women ordinarily cared for their small and simple gardens.

The Ebb 1870

After some years of cultivating and harvesting, farms on relatively poor land began to show signs of exhaustion in smaller yields. Farms on the steeper hillsides lost their top soil as the rains washed away the exposed earth. The families on these farms found themselves obliged to move. Many migrated to the new western lads where wheat could be grown more cheaply and brought to the eastern market by the Erie Canal. But the farms on the naturally good soils of the bottom lands and the gentler limestone slopes remained prosperous and the people stayed.

On the abandoned lands the forest generally grew up more into oaks than pines, and the reduced fertility of the soil was shown by the poorer growth of timber, which was cut from time to time. On limestone outcrops red cedar came in; on the drier ridges chestnut, oaks were cut for charcoal. Shrubby growth, such a sumac bushes, was often the pioneer on abandoned land.

Native Ingenuity had developed a number of interesting labor saving devices and specialized tools. By this date American farms were becoming characterized by a growing complexity of equipment. The thrashing and mowing machines had appeared. Permitting one man to care tor a much larger number of acres than he could previously.

Wood was being replaced by metal. The horse, however, continued as the major source of power.

1950

The modern farmer cultivates only land which yields a profit. He is aware of the necessity of proper measures to conserve the natural fertility of the soil. He prevents erosion by contour plowing and strips cropping, and soil exhaustion by fertilization and rotation of crops. Because of rapid transportation by truck and railroad, this area has developed into dairy farms which supply New York City with milk.

The land that was abandoned has returned to second growth forest. Marketable timber is now scarce and the woodland of oak, hickory, birch and maple today supply mostly firewood. Chestnut has disappeared because of the chestnut blight which was brought into the country through the activities of man. With careful management the forest will again produce valuable timber.

The invention of the gas engine, combined with the remarkable development of specialized machines and equipment, made possible the mechanized farming of our time. The tractor as the source of power can now be couple with a great variety of metal tools that prepare the soil, plant the seeds, cultivate the growing plants and harvest the crop. The grass is cut and the hay baled mechanically. All this makes machinery a large part of the farmer’s investment, but it also permits him to reduce human labor and increase his production per man hour.

Agriculture

Part of Hall of New York State Environment.