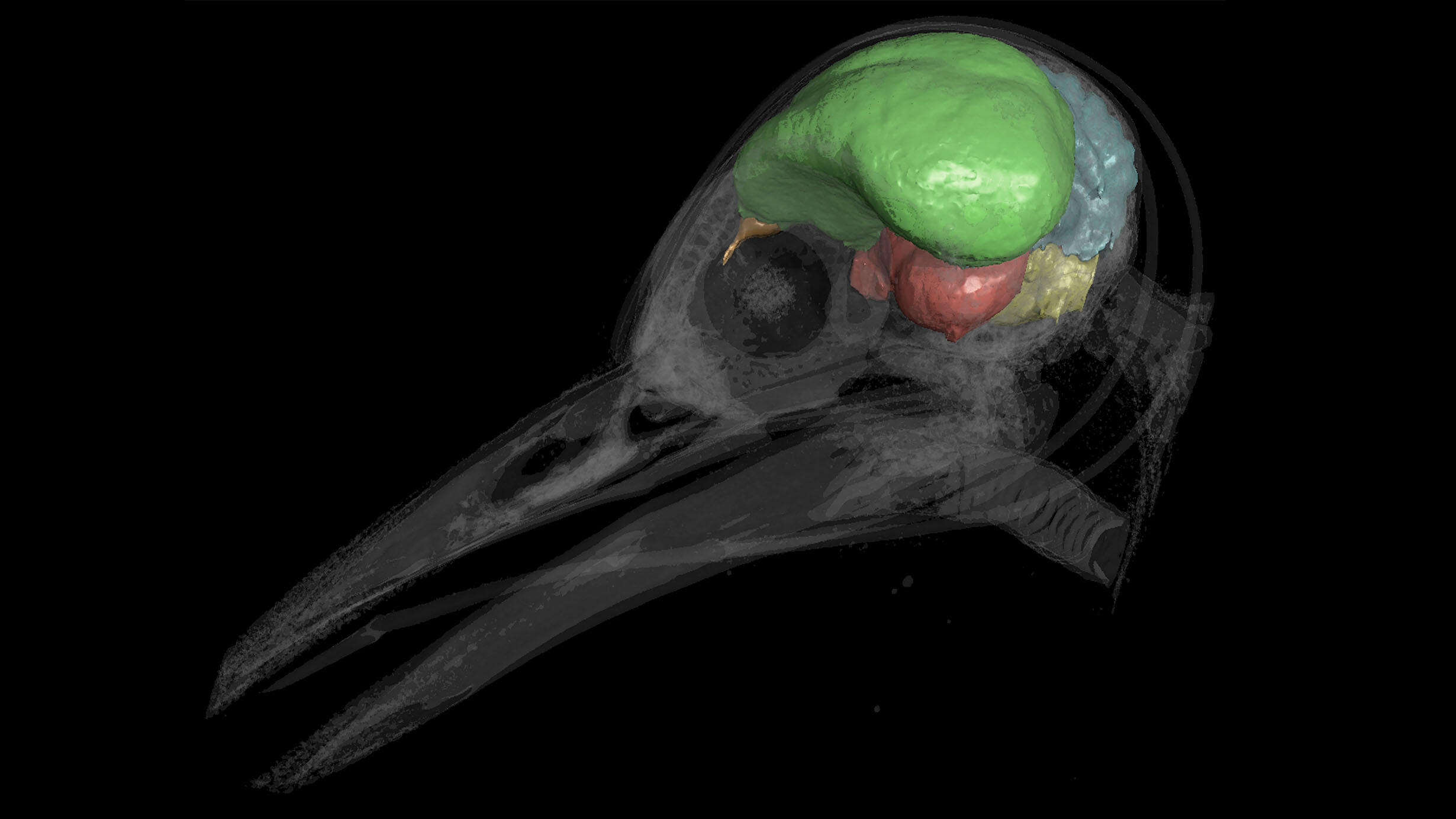

This CT scan shows a modern woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons) with its brain cast rendered opaque and the skull transparent. The endocast is partitioned into the following neuroanatomical regions: brain stem (yellow), cerebellum (blue), optic lobes (red), cerebrum (green), and olfactory bulbs (orange).

This CT scan shows a modern woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons) with its brain cast rendered opaque and the skull transparent. The endocast is partitioned into the following neuroanatomical regions: brain stem (yellow), cerebellum (blue), optic lobes (red), cerebrum (green), and olfactory bulbs (orange).A. Balanoff/© AMNH

New research reveals some surprising details about how they have evolved relative to the brains of their close cousins, dinosaurs and alligators.

“The brains of birds are as large as many mammals and allow for intelligent behaviors such as learning songs and solving complex puzzles,” said Aki Watanabe, a Museum research associate and an assistant professor at the New York Institute of Technology who is the lead author of the new study, published this week in the journal eLife. “These features make bird brains an excellent system to compare with how humans and other mammals obtained large and unique brains, yet we know relatively very little about how bird brains got to be that way.”

Watch a SciCafe about which came first—the bird, or the brain?

To examine these dynamics in birds, the researchers focused on a sample of modern and extinct birds, their dinosaur precursors, and alligators, which are close living relatives to birds. The team also acquired developmental sampling of domestic chickens and American alligators.

High-resolution X-ray computed tomography (CT) imaging and high-density mathematical shape analysis were used to visualize, model, and statistically analyze how the shape of the brain cavity—an accurate proxy for the brain—changes through both evolutionary and developmental processes.

The researchers found that the way avian brains change with body size is different from that process in either dinosaurs or alligators. That "scaling relationship," as it is called, dictates how avian brains develop and evolve, on a unique path from dinosaurs or alligators.

Birds were also found to have a more integrated brain structure—a surprising result, because the researchers initially thought that bird brains, with their inflated forebrain, would be more modular than their dinosaurian counterparts, similar to the way modern humans’ brains are more modular than those of other primates.

AKI WATANABE (Research Associate, Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History): Are dinosaurs still alive today?

[Watanabe on screen speaking to camera. Text reads: “Are dinosaurs still alive today?”]

[MUSIC] [BOOM]

[The American Museum of Natural History logo pops up along with the text “Space Vs Dinos” over a background of an illustrated asteroid and an illustrated dinosaur skull. Watanabe appears on screen again with the text “Aki Watanabe, Paleontologist”]

WATANABE: The remarkable answer is that dinosaurs are still alive,

[In a circle to the right of Watanabe, text appears: “Dinosaurs ARE still alive.”]

WATANABE: but you don’t need to go looking for them on some deserted island.

[An island with a palm tree on it slides over the text in the circle with a [SPLASH]. A line is drawn through the center of the circle to make it into a “not” sign.]

WATANABE: They’re actually all around us

[The island is replaced by an illustrated human form with arms outstretched, covered in pigeons.]

WATANABE: because all birds are dinosaurs.

[Text reads: “All birds ARE dinosaurs.”]

WATANABE: Not only did birds evolve from dinosaurs,

[A pigeon and a T. rex pop up on screen and an arrow is drawn between them.]

WATANABE: scientifically they are dinosaurs,

[The arrow is replaced by an equals sign.]

WATANABE: just like how us humans are primates.

[On either side of the equals sign, the pigeon and T. rex disappear and are replaced by a human and a monkey. A blue screen rows of dinosaur animations scrolling from side to side slides over the screen.]

WATANABE: Sixty-six million years ago an asteroid impact did kill off a lot of the dinosaurs,

[Text reads: “66 Million Years Ago.” A flash of white and orange occurs on screen. One by one the dinosaurs start to swirl into dust.]

WATANABE: but one lineage survived

[Eventually all the dinosaurs are gone except an illustration of Archaeopteryx, which enlarges to almost fill the screen.]

WATANABE: and these are the ancestors of all modern birds.

[Lines draw out from the Archaeopteryx to circles containing footage of live birds: pigeons, chickens, flamingoes, penguins, hawks, owls, ostriches, etc.]

WATANABE: To this date paleontologists have never found a non-bird dinosaur

[An illustrated T. rex chases after a human figure, who is [YELLING] and waving its arms.]

WATANABE: that was alive after the extinction event.

[Text covers the animation: “This didn’t happen.” Watanabe reappears on screen.]

WATANABE: Even if we did, we’d be too excited to keep it to ourselves.

[An illustrated pigeon appears on screen.]

[COOING]

WATANABE: Now that we know birds are dinosaurs,

[Above the pigeon, a checkmark appears next to the word “Dinosaur.”]

WATANABE: some of you may be disappointed that modern dinosaurs that are alive today don’t really look like dinosaurs from the Mesozoic Era.

[Three human figures slide in from the left and contemplate the pigeon. Above them, text reads: “not scary,” “too fluffy,” “kinda gross,” “not roaring,” “no teeth,” “too small,” “where are horns.”]

WATANABE: But new research is finding that

[The pigeon and onlookers slide offscreen. A new human figure appears, and catches a magnifying glass that falls from the top. It uses the magnifying glass to examine an illustrated T. rex head.]

WATANABE: dinosaurs had a lot of the important features we associate with birds today.

[The human figure walks with the magnifying glass to a computer to the right. It bangs on the keyboard and the computer flashes back: “KINDA BIRD-Y.” Watanabe reappears on screen.]

WATANABE: For example, we now know that many of the dinosaur groups had feathers,

[Behind Watanabe, feather-like things float down from the top of the screen.]

WATANABE: or precursors to feathers we call protofeathers.

[Text reads: “Protofeathers.”]

WATANABE: Because these dinosaurs clearly didn’t fly,

[A T. rex tries in vain to “flap” its tiny arms.]

WATANABE: we think that feathers first evolved for regulating body heat or for display.

[A dinosaur with blue and red arrows pointing in and out of it replaces the T. rex. Then a dinosaur with wing-like arms replaces the previous dinosaur. It scales to fill the whole screen. It raises its arms to show its feathers, saying “I look so good!” A peacock appears next to it and says “Whatever.”]

WATANABE: Dinosaurs, like birds, already had

[Under the feathered dinosaur, the word “Dinosaurs” appears. Under the peacock, the word “birds” appears. A bracket draws in above them.]

WATANABE: high metabolisms,

[A circle appears above the bracket with a beating heart in it. Text reads “High metabolism”. The circle slides to the left.]

WATANABE: hollow bones that made them lighter,

[A circle appears with the outline of a bone inside. Text reads “Hollow bones.” The circle slides to the right.]

WATANABE: wishbones,

[A circle appears with an illustrated wishbone inside. Text reads “Wishbones.” The circle slides to the left.]

WATANABE: and also relatively large brains for their body size.

[A circle appears with the outline of a brain. The brain grows larger and more round with the sound of a balloon inflating. Text reads “Large brains.” The circle slides to the right.]

[This diagram is replaced by detailed illustrations of different dinosaurs with feathers, some looking like ostriches and some looking like crows or other types of birds.]

WATANABE: So collectively, dinosaurs may have looked a lot like birds, and if you were dropped off in an environment in the Mesozoic era,

[Text reads Mesozoic era. A human form drops into the center of the frame and looks around. To its left an oviraptor illustration appears.]

WATANABE: you might actually mistake some of the dinosaurs for turkeys.

[A thought bubble appears over the human’s head and inside the bubble an illustration of a turkey with question marks around it appears.]

[TURKEY GOBBLE]

[The oviraptor takes a hop towards the human with text that reads “Gobble gobble.”]

[DEEP VOICE SAYING “GOBBLE GOBBLE”]

[The human’s thought bubbles pop and disappear, and the human runs offscreen in fear. Watanabe reappears on screen.]

WATANABE: So the next time you see a humble pigeon,

[In a circle to the right of Watanabe, an illustrated pigeon appears.]

WATANABE: just remember the fact that they’re part of a very successful lineage that survived the mass extinction event 66 million years ago

[A trophy and a medal appear next to the pigeon.]

WATANABE: that wiped off all the other dinosaur groups.

[The image of the pigeon fills the screen and we see that the pigeon is standing on an award platform in 1st place. A skull of a triceratops sits in 2nd place and a skull of a brachiosaurus sits in 3rd place. In the distance, ghosts of an oviraptor and a T. rex with halos above their heads.]

[Credits roll. Watanabe appears in the bottom right corner of the screen.]

WATANABE: Thanks for watching. If you want to learn about life in the universe elsewhere, click the link above for this week’s space video. And if you have any questions about dinosaurs, leave them in the comments section below. Don’t forget to subscribe to the AMNH channel for more videos like this.

[END MUSIC]

“Bird brains develop and evolve in a more coordinated way, in which a change in one brain region is associated with predictable changes in another region, like squeezing on a balloon or an inflated toy,” Watanabe said.

It could be that the bird brain evolves and develops in a highly coordinated way because of shared functional, developmental, or physical forces, which could be investigated in future studies.

The researchers also found that brain evolution along the dinosaur-bird transition occurred in a stepwise fashion. Non-bird dinosaurs already had an “avian”-grade optic lobe and cerebellum with respect to their shape, which are important for visual input and motor coordination.

Read more about how dinosaur brains led to modern birds.

Historically, these regions were thought to have co-evolved with the evolution of powered flight, but the new study further supports the idea that dinosaurs already possessed an advanced cerebellum and optic lobes prior to the origin of birds.

“This suggests that vision was an important aspect of dinosaurian lifestyle, perhaps for recognizing an array of color patterns on their feathers, active predatory behaviors, or even an indication of limited wing-assisted locomotion capabilities in some of the dinosaurs we sampled that are very closely related to birds,” Watanabe said.

Other Museum authors on this study include Division of Paleontology and Macaulay Curator Mark Norell, and Research Associates Amy Balanoff, Paul Gignac, and Eugenia Gold.