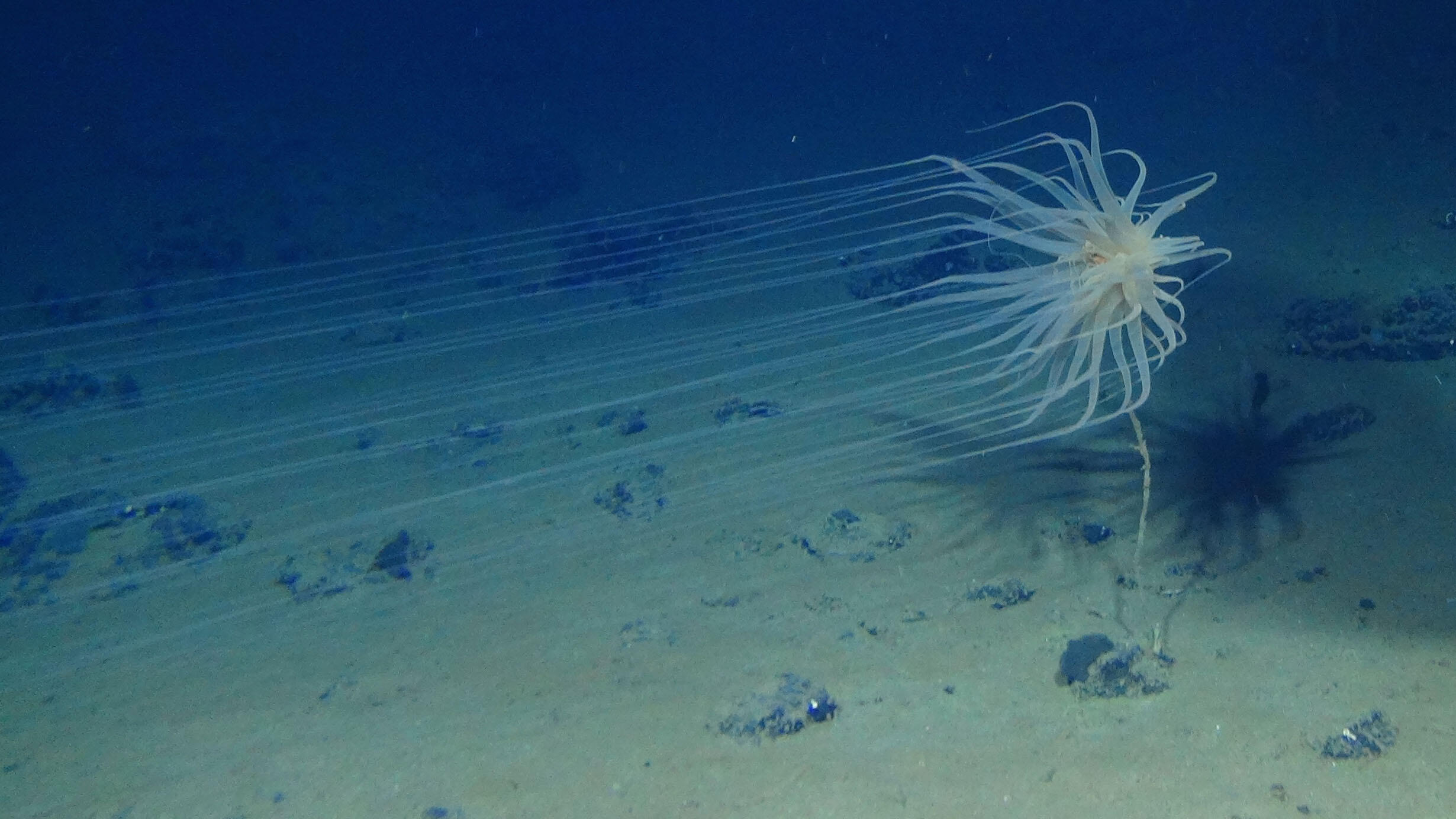

Relicanthus daphneae, a marine organism first described as an anemone in 2006, has pale purple or pink tentacles that can extend almost 7 feet long.

Relicanthus daphneae, a marine organism first described as an anemone in 2006, has pale purple or pink tentacles that can extend almost 7 feet long.Craig Smith & Diva Amon, ABYSSLINE Project

If it looks like an anemone and moves like an anemone, but its DNA isn’t a perfect match, can it be called an anemone? New research suggests that a mysterious animal that has puzzled scientists for nearly 50 years is, indeed, a sea anemone—at least for now.

First discovered in the 1970s, and found living around the periphery of deep-sea hydrothermal vents around the world, the marine species now known as Relicanthus daphneae is unusually large for an anemone, with pale purple or pink tentacles that stretch almost 7 feet long. Based solely on its anatomy, the animal was first described as an anemone in 2006. Eight years later, however, a Museum study based on five genes concluded that it was not an anemone and belonged outside of the order Actiniaria.

A 2014 study posited that the deep-sea animal may be better placed in a newly-created order.

But recent work, which includes some of the same researchers from the 2014 study, indicates that the enigmatic animal does indeed belong among sea anemones, albeit as its own suborder.

The new, more robust study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, includes an analysis of the complete mitogenome—DNA from the mitochondria, the “powerhouse of the cell,” rather than the nucleus. Although the DNA findings still place Relicanthus outside of sea anemones, as a “sister” group, the researchers decided it belongs within Actiniaria because of a re-evaluation of its anatomy, in particular its cnidae, or stinging capsules.

Put simply: “They have flaps,” said Mercer R. Brugler, a Museum research associate and associate professor at the New York City College of Technology (CUNY). “All of the other anemones have flaps, and nothing outside of anemones has flaps.”

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Benthic Deepwater Animal Identification Guide

These flaps are essential to the firing ability of sea anemone nematocysts, capsules within their tentacles that harbor coiled stingers. The nematocysts fire with the fastest mechanism in the animal kingdom, occurring in less than three milliseconds.

“The flaps are the lids of the stinging capsules—it’s how they open,” said Estefanía Rodríguez, a curator in the Museum’s Division of Invertebrate Zoology and a corresponding author on the new study. “When we studied these in more detail, it’s very difficult to make the case that such specialized anatomy evolved multiple times, which is why we think this giant sea animal really is an anemone, and not a separate part of the cnidarian family tree.”

The new suborder that was created to accommodate Relicanthus was named Helenmonae in honor of the Museum’s Helen Fellowship program—under which the study’s lead author Madelyne Xiao was funded—and in combination with the Latin name for anemone.

The researchers propose that the phylogenetic oddities of Relicanthus could be due to its association with the periphery of hydrothermal vents, which are essentially hot springs on the seafloor.

“We speculate that if it truly is associated with these vents, perhaps it is using its long sticky tentacles to snag, and eat, some of the more mobile animals coming in and out of the vent field—which serves as a concentrated buffet of organisms,” Brugler said. “In that case, it would have a relatively stable food source over long evolutionary timescales.”

But if history is an indicator of the future, this is likely not the last time Relicanthus gets a new spot in the tree of life.

“We’ve found that every time we increase the size of the data set, things change,” Rodríguez said. “It’s amazing that even 50 years after this animal was found, we still don’t know for sure what it is.”