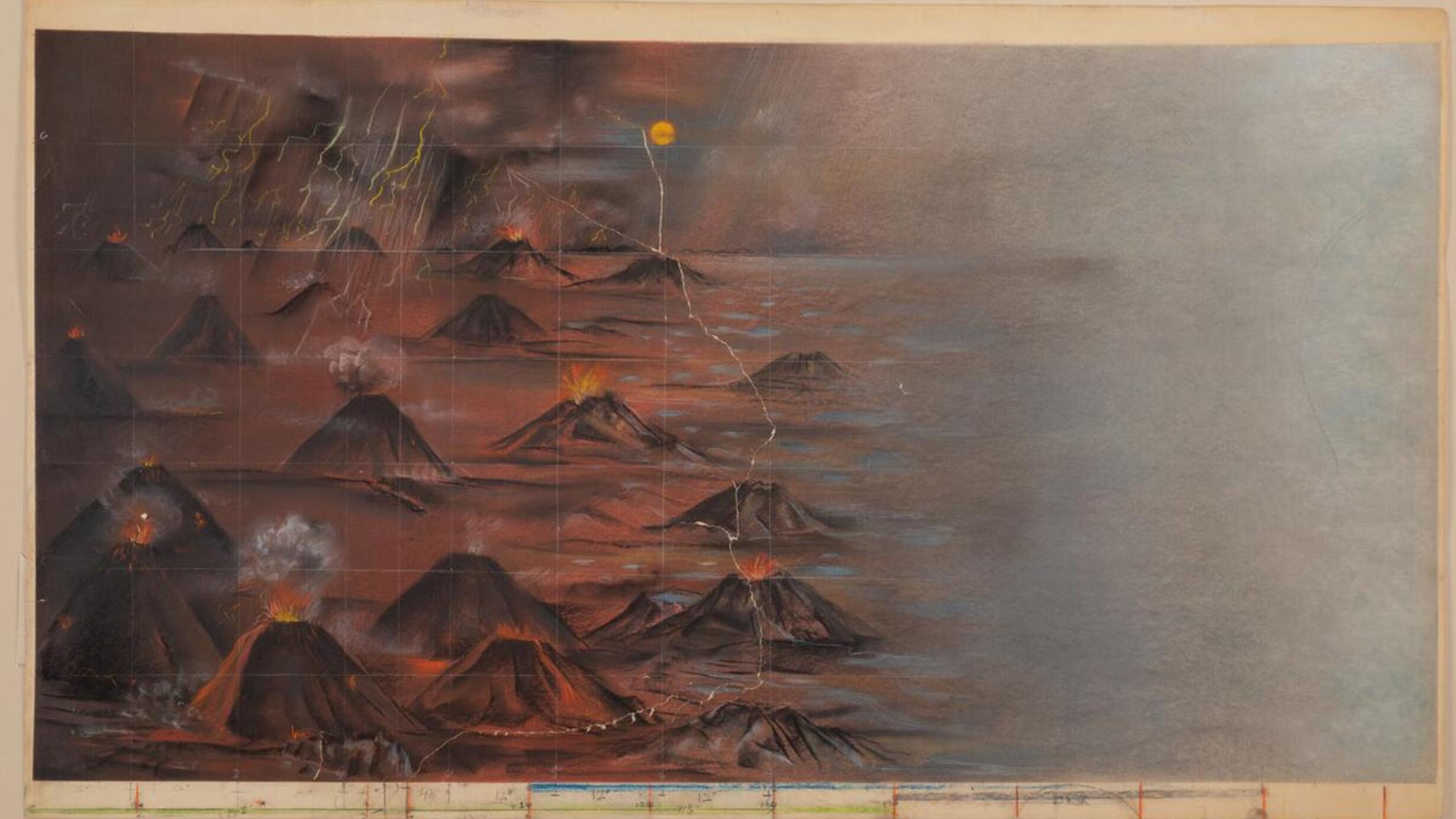

Study for the Origin of Life case, Pastel on paper, Charles Henry Alston, 1964, AMNH Library image: art-100101660-01

Study for the Origin of Life case, Pastel on paper, Charles Henry Alston, 1964, AMNH Library image: art-100101660-01Matthew Shanley/©AMNH

Charles Henry Alston (1907-1977) was an influential painter of the Harlem Renaissance and the first African American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration. He managed the WPA murals created at Harlem Hospital, leading a staff of thirty-five artists and assistants. Surprisingly, several of his artistic works have been on permanent exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History and one is still on display in 2023. Alston was the first African American to teach at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Students League and, in 1969, he was appointed the painter member of the Art Commission of the City of New York.

Alston was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, and was related to the artist Romare Bearden through his mother's second marriage. He attended Columbia University as an undergraduate and graduate student, receiving a B.A. from Columbia College in 1929 and an M.F.A. from Columbia University's Teachers College in 1931. He was later awarded the Arthur Wesley Dow Fellowship which funded graduate work at Columbia’s Teachers College. It was during his time there that he designed the cover for one of Duke Ellington’s jazz albums, as well as book covers for Langston Hughes and Eudora Welty, assignments that led to a successful career as an illustrator for popular magazines during the 1930s and 1940s. A self-described “figure painter,” Alston embraced abstraction, but never completely abandoned the figural.

After graduating he worked at the Harlem Arts Workshop, when the program required more space, he secured an additional facility at 306 W. 141st St. This space, known as "306," became a center for intellectual and creative exchange for the Harlem art community. A pivotal figure within the Harlem Renaissance, Alston was dedicated to empowering African Americans through cultural enrichment and artistic advancement. In his distinguished career as an artist and an educator, he continually sought to reclaim and explore racial identity and its complicated implications. He was appointed the first African American supervisor within the Federal Art Project in 1935; he capitalized on his new position by forming the Harlem Artists Guild in hopes of convincing the Works Progress Administration to fund more African American artists.

Although he participated in the 1933 Harmon Foundation exhibition, Alston later joined Romare Bearden, Augusta Savage, and others in boycotting the program due to its segregated format. Eager to explore political and aesthetic topics in African American art, Alston also cofounded the art collective known as the Spiral Group in 1963.

The influence of Mexican muralists José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, who all used murals to inspire people toward social activism, can be seen in Alston’s work. When Diego Rivera was painting his famous mural at Rockefeller Center, which was destroyed because of its political content, Alston frequently visited the Mexican artist, communicating in French, their only common language.

Alston was also a talented sculptor and illustrator. His bust of Martin Luther King was the first piece of art by and African American to enter the White house collections. His cartoons and illustrations were published in popular magazines such as The New Yorker and Fortune. During World War II, he worked at the Office of War Information and Public Information, creating cartoons and posters to mobilize the black community to join in the American war effort.

He and other artists also looked toward West Africa for inspiration, making personal connections to the stylized masks and sculpture from Benin, Congo, and Senegal, which they viewed as a link to their African heritage. It is unknown if Alston spent any time doing research at the AMNH, but it was one of the only places in New York City that had African art on permanent display, first installed in 1911.

In 1958, Alston was commissioned by the AMNH to paint a mural in the Hall of North American Forests. It is unknown why Alston was chosen, but he was a member of the National Society of Mural Painters, and the employment record shows that he was recommended by Gordon Reekie, the Director of Exhibitions and Graphics. The mural is painted directly onto the painted plaster wall and illustrates the water cycle found in forests. It is not signed, nor does it have any public designation that Alston is the artist.

Matthew Shanley/©AMNH

In 1964, Alston was commissioned again to paint a mural titled “The Origin of Life" for display in the new Hall of the Biology of Invertebrates. This mural evoked the Miller-Urey 1952 experiment that simulated the conditions thought at the time to be present on early, prebiotic life, in order to test the hypothesis of the chemical origin of life under those conditions.

Matthew Shanley/©AMNH

©AMNH

Jackie Beckett, Denis Finnin/©AMNH

The Biology of Invertebrates Hall was removed in 1996 in preparation for the new Hall of Biodiversity. Alston’s mural, with its attached plexiglass molecule models is preserved in AMNH Special Collections.

Alex Rota/©AMNH

Alston’s Biology of Invertebrates Hall mural is one of the few instances when the Museum distributed a separate press release on the artist who created part of an exhibit. The press release dated May 18, 1964 notes “The mural suggests the eerie atmosphere of the primitive earth when dry heat, raging volcanos, ionizing radiations from cosmic rays and from radioactive elements with the newly-completed crust, and violent bolts of lightning all acted as agents in the formation of the first complex molecules from simple, primitive gases. Among those early chemical compounds were amino acids, which are the materials from which proteins are made and thus represent a vital first step in the creation of life…”

The AMNH Library also has three paintings by Alston depicting FDR and Abraham Lincoln. It is unknown how these 3 paintings entered the collection, which were first noted in 1955, and perhaps they were given by Alston as examples of his work when he was commissioned for his first mural.

Matthew Shanley/©AMNH

Joel Sweimler’s position of Library Exhibition Researcher is generously supported by The Future of Truth, a multidisciplinary program of the University of Connecticut's Humanities Institute, funded by the Henry Luce Foundation.