How is the statue understood today?

Part of the Addressing the Statue exhibition.

Although the monument in front of the Museum is often referred to as the Roosevelt Statue, two other men are also depicted with Theodore Roosevelt.

Explore the three figures represented in the Theodore Roosevelt Equestrian Statue:

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) is often considered the first “modern” U.S. president because he expanded the power of the office in ways that continue to this day. While in the White House, he fought to rein in the power of big business, to improve conditions for workers, and to implement better health and safety laws.

Roosevelt is also known as the “Conservation President”—during his presidency, more than 230 million acres of land were set aside as national parks, national forests, and other protected sites.

But Roosevelt also held some disturbing views, including that the “English-speaking race” was superior to others. Roosevelt—like the country he led—has a complicated and sometimes troubling history. Nevertheless, he is widely considered one of the most important American presidents.

Explore the Theodore Roosevelt timeline.

“Theodore Roosevelt was the explorer-naturalist par excellence. All the things that the Museum’s trying to do with science education—he was the leader in this. T.R. was a promoter of scientific experts, particularly naturalists, so it makes sense for him to be honored at the Museum.”

—Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History, Rice University

Mark Simons/Purdue University

Mark Simons/Purdue University

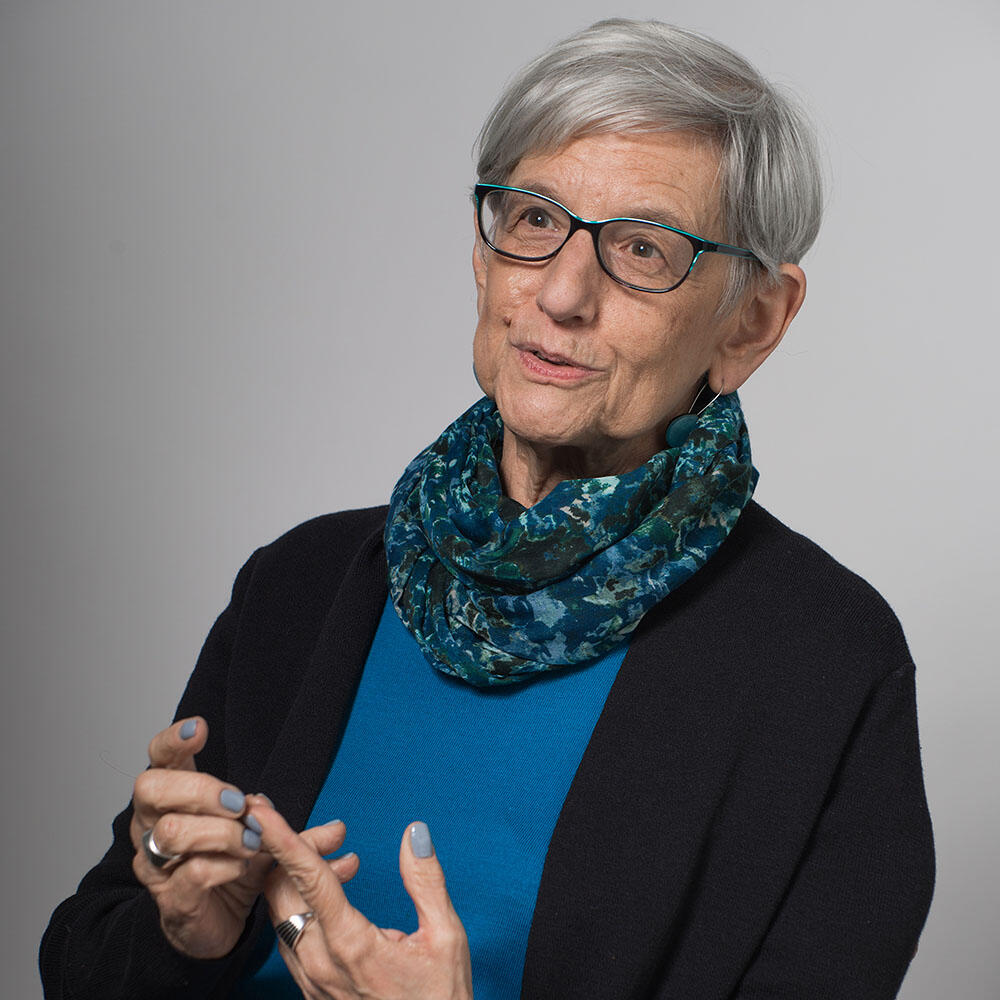

“You have this very robust white male, Theodore Roosevelt, on his horse, who is as muscular as Roosevelt is. And then trailing behind are the African and the Native American, in a very subservient role. [The sculptor] portrayed them in a very dignified way, but their position of subservience remains.”

—Mabel O. Wilson, Professor of Architecture and African American Studies, Columbia University

Courtesy Mabel O. Wilson

Courtesy Mabel O. Wilson

“Roosevelt's up on the horse and he's on some kind of hunting expedition like he often did. And he has two gun-bearers: one is African and one is Native American. The artist saw this as Roosevelt leading two continents into the 20th century.”

—David Hurst Thomas, Curator of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History

D. Finnin/© AMNH

D. Finnin/© AMNH

Multiple Perspectives on Theodore Roosevelt

Important President

"Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most important presidents in American history and he showed us what an activist federal government could do. He is our great conservation president. During his tenure in office, he saved over 234 million acres of wild America."

"When he ran in the Progressive Party in 1912, you have African-American leaders, socialists, Jane Addams [all] behind him, because he was closer to the ideal we have today of integration and equality than the other political characters of the era." —Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History, Rice University

Complicated Legacy

“When we think about Roosevelt as a conservationist, we think about when he designates land as national forests or national parks. In almost all cases, that's Indian land...Roosevelt's conservationist acts carry with them devastating consequences for Indian people."

—Philip Deloria (Dakota descent), Professor of History, Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University

"Yes, I would absolutely call Theodore Roosevelt a racist. He had very specific views around which races—the Nordic, the Alpine—were going to lead [American] civilization forward.”—Mabel O. Wilson, Professor of Architecture and African American Studies, Columbia University

“When people look at certain historical figures in a revisionist light, others will say, you shouldn't judge them by the standards of the present. But even by the standards of his own day, you could find lots of opposition to [Roosevelt’s] opinions, beliefs and policies among his own peers.”

—Andrew Ross, Director of American Studies Program, New York University

R. Mickens/© AMNH

R. Mickens/© AMNH

“I think the American Museum of Natural History should memorialize Teddy Roosevelt for his contributions to conservation. I think memorialized is different than celebrated. We should also acknowledge his racism and race politics. We have to remember these iconic figures in American history were flawed and complicated. History is complicated.”

—Monique Renee Scott, Director of Museum Studies, Bryn Mawr College; Consulting Scholar, Penn Museum

Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College

Native American Figure

The designs of the headdress, medallions, and necklace seen on this figure resemble styles worn by Native people from the North American Plains.

This region is home to a diverse array of Native cultures, each with their own language and distinct traditions. Find out more about Plains cultures today.

The sculptor of the statue, James Earle Fraser, grew up in Minnesota and South Dakota and was familiar with Plains cultures. But he did not distinguish among the many Plains nations when designing the statue. The result is a depiction of a Native person that, like many in popular culture, reflects common stereotypes.

"What we see is a romanticized, generic Plains Indian. The sculptor grew up with Plains Indians and was really wistful that they were disappearing. He felt that Native American culture needs to be preserved, and if it can't be preserved in reality, then it can be preserved in statuary in front of one of the great natural history museums of the world.”—David Hurst Thomas, Curator of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History

“I think the statue invites people to forget about Indians again. Anytime you see an Indian with a headdress on, you think you’re in the 19th century and then you don't have to think about a contemporary Indian. A kid with a skateboard, a hip-hop artist, a politician. That's what Indian country is today. It’s full of interesting people.”—Philip Deloria (Dakota descent), Professor of History, Harvard University

“I teach a course on monuments and when my students look at this statue, they’re immediately suspicious of the hierarchical representation. They also point out that we’re used to seeing Plains Indians riding horses when they’re shown in statues—not walking alongside someone! Even within the familiar idioms of Western art, the statue is odd.”

—Scott Manning Stevens (Akwesasne Mohawk), Professor of English and Native American & Indigenous Studies, Syracuse University

D. Finnin/© AMNH

D. Finnin/© AMNH

“The Native American is a composite of many tribes. The figure is an allegory standing for a continent, similar to the way many public statues of nude women represent virtues or vices.”

—Harriet F. Senie, Director, M.A. Art History, Art Museum Studies, The City College of New York

R. Mickens/© AMNH

R. Mickens/© AMNH

African Figure

Some scholars think that the patterns on the shield suggest this figure was based on people from the Maasai culture. Yet the hairstyle and facial scarification on the figure do not accurately reflect Maasai traditions.

Some scholars think that the patterns on the shield suggest this figure was based on people from the Maasai culture.

Some scholars think that the patterns on the shield suggest this figure was based on people from the Maasai culture.D. Finnin/© AMNH

The hairstyle and facial scarification on the figure do not accurately reflect Maasai traditions.

The hairstyle and facial scarification on the figure do not accurately reflect Maasai traditions.D. Finnin/© AMNH

The Maasai speak the Maa language and historically lived along what’s now the border between Kenya and Tanzania, a region that includes parts of the Serengeti and Mount Kilimanjaro. Find out more about the Maasai today.

The sculptor, James Earle Fraser, would likely have known that Theodore Roosevelt met Maasai people while traveling in East Africa. While Maasai men carry and drape cloth around their bodies, the way Fraser depicts that here more closely resembles styles seen in Greek and Roman statues.

“People referred to this figure as an African-American but it was intended to represent Africa, as the Native American represents America. Fraser grew up with Native Americans but he was not familiar with Africans so he used the classical Greek and Roman tradition to represent this body.”

—Harriet F. Senie, Director, M.A. Art History, Art Museum Studies, The City College of New York

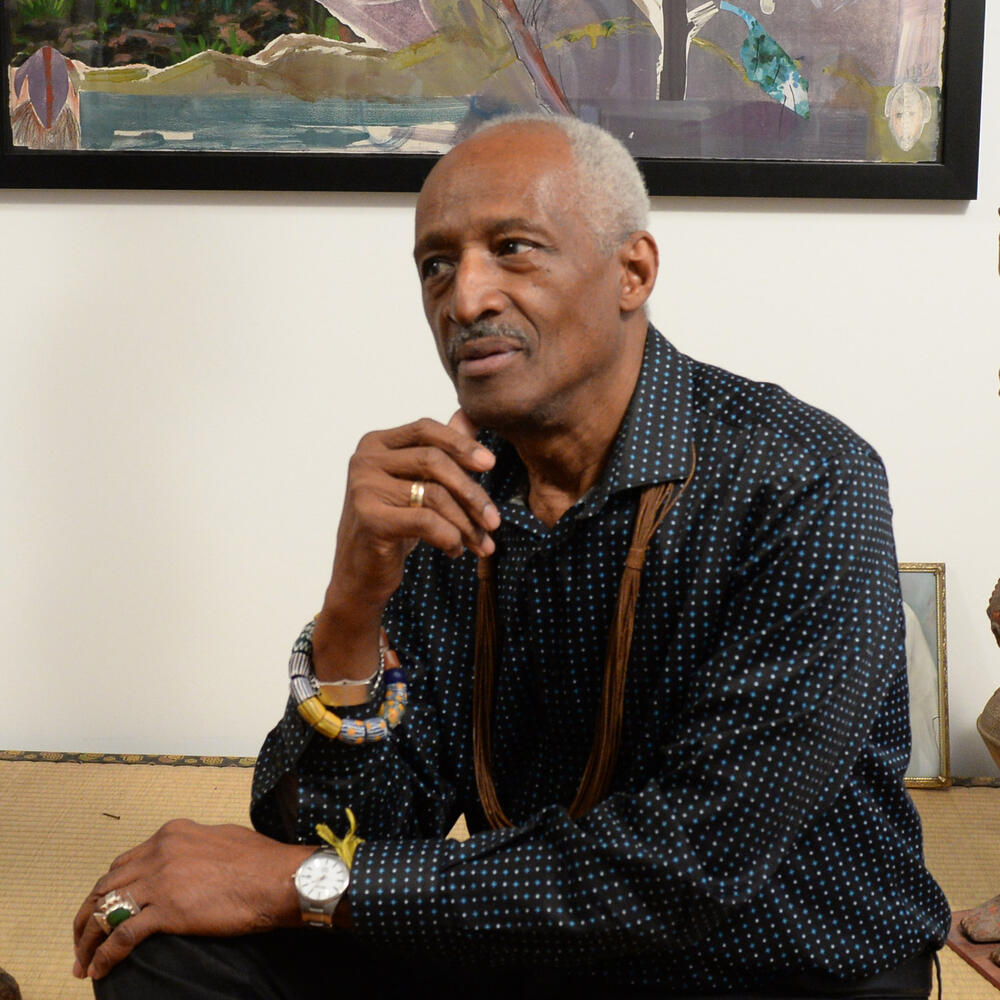

“The design of the shield is characteristic of the Maasai and Samburu peoples of East Africa, particularly Kenya…. Roosevelt visited what was called German East Africa where he most likely met the Samburu and Maasai.”—George Nelson Preston, co-founding director and chief curator, Museum of Art and Origins

Frank Stewart

Frank Stewart

© AMNH Library

“With the Native American, the gun is pointed down, which says that the Indian wars are over and they’ve lost. With the African, the rifle is still up, which suggests that the African continent has not yet been fully conquered. So [the statue is] a narrative of empire and conquest, of Africa and the New World, by the white European.”

—Mabel O. Wilson, Professor of Architecture and African American Studies, Columbia University

Courtesy Mabel O. Wilson

Courtesy Mabel O. Wilson

"I would call it a monument to white supremacy because of the [portrayal] of the three figures: the figure on horseback who is clearly superior and relying on the labor of those on foot who are clearly in a subordinate position."—Andrew Ross, Director of American Studies Program, New York University

“The African and Indian faces seem sort of dignified. But you know, being dignified, and accepting your place, is a lie! Isn’t it?”

—Sokari Douglas Camp, Sculptor, Honorary fellow, University of Arts, London, and School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

© Sal Idriss/National Portrait Gallery, London

© Sal Idriss/National Portrait Gallery, London