Timeline: Robert Scott Expedition

Part of the Race to the End of the Earth exhibition.

December 1910

Scott's Voyage South Starts With Near Disaster

The Terra Nova Nearly Goes Under Two Days Into Expedition:

Terra Nova left New Zealand for the Ross Sea on November 29, 1910. Just two days later, the expedition nearly came to a bad end in a mighty storm. Too small for its load and packed to the brim, the leaky old whaler was at risk even before the storm brewed. Laboring into the gale, the ship began to take on water. The pumps, clogged after a few hours by a thick, gummy paste of coal dust, dirt, and oil, eventually stopped working altogether. Bucket brigades, composed of officers, men, and scientists alike, struggled hour after hour in the dark. "It was a sight that one could never forget," Lieutenant Edward "Teddy" Evans, Scott's second in command, would recall. "Everybody saturated, some waist-deep on the floor of the engine room, oil and coal dust mixing with the water and making everyone filthy, some men clinging to the iron ladder-way and passing full buckets long after their muscles had ceased to work naturally, their grit and spirit keeping them going."

Skidding Supplies, Flailing Dogs and Falling Ponies: The Terra Nova's Deck Turns Into a Chaotic Scene

On deck things were increasingly desperate. The ship's coal bunkers were too small to accommodate all of the coal required, so the excess–thirty tons of it–was stored in sacks on the main deck, along with lab supplies, sheep carcasses, motor sledges, dogs, and ponies, all packed tightly wherever they might fit. During the storm many of the sacks became loose and skidded back and forth across the planking, hammering away at the ship's rails. Worse, overloading had affected the ship's buoyancy and handling. The only way to avoid catastrophe was to push some of the topside coal into the sea, even though there was no way of getting more.

The animals also suffered. Many of the thirty-three dogs, on short chains to keep them from fighting on the way south, were nearly strangled each time a breaching wave raced across decks. Ponies in cramped stalls in the forecastle slammed from wall to wall with each roll of the ship, legs flailing as they tried but failed to keep their footing, going down hard on their buckled limbs in pools of vomit and excrement. If it were not for their handler, Captain Lawrence "Titus" Oates, literally forcing them onto their feet after they had fallen, it's unlikely that any would have made it through that long night uninjured.

Storm Breaks; Scott and Crew Move Forward

Finally, on December 3 the winds and the sea began to calm. The toll was heavy. Two of the ponies were dead, two others badly injured; one dog had drowned. The decks were covered with debris, equipment, and broken cases, and everything was thoroughly soaked. But they had survived, and soon Scott was in better spirits. "The scene was incomparable," he wrote a week later as they entered the southern pack, the fluctuating expanse of sea ice that annually surrounds Antarctica. "The northern sky was gloriously rosy and reflected the calm sea between the ice, which varied from burnished copper to salmon pink; bergs and packs to the north had a pale greenish hue with deep purple shadows, and the sky shaded to saffron and pale green. We gazed long at these beautiful effects."

January 1911

The British Break Through Pack Ice and Reach Antarctic Shores

Scott Chooses Cape Evans on Ross Island for His Base Camp

It took almost three weeks to get through the pack ice barricading the way into the Ross Sea. The ship burned through coal rapidly in order to ram through ice floes, raising Scott's concern whether the dwindling supply of coal would be adequate for their winter needs.

They finally punched through to open water on December 30, 1910, and on January 2, 1911, they spotted Mount Erebus, the huge volcano that dominates Ross Island – their intended destination. Scott's original plan was to try to set up their hut on the beach below Cape Crozier, on the island's east end. However, the swell off the cape was dangerously high, and the ice cliffs looming next to it excessively dangerous.

Deciding to go west instead and enter McMurdo Sound, Scott chose Cape Evans as the best place for base camp. Lumber and prefabricated sections for the base hut were moved onto the building site.

Navy Rules: Hut Divided Into Mess Deck and Ward Room by a Wall of Packing Cases, Dividing Officers and Scientists From Crew

On January 18, 1911, the new hut was ready to be inhabited. Scott divided it as though they were still aboard ship: The sixteen officers and scientists were given two-thirds for their quarters and labs, while the nine seamen and support personnel occupied the rest. Officers and men ate separately, although the food served was the same. Observance of class and social divisions 'tween decks was still automatic and unquestioned in the Royal Navy, and so it would be in Scott's Antarctic.

January–February 1911

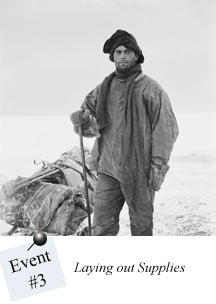

Laying Out Supplies for the Impending Attempt at the Pole

Bad Weather and Poor Transportation Choices Hinder Plans

Once the hut at Cape Evans had been erected and stores stowed in their proper places, it was time to start laying depots for next summer's journey to the pole. Scott estimated that he and his men had about a month's time to lay a series of food and fuel dumps along the first part of his intended path to the pole. This was vital: There was no way that they could carry everything they would need on a round trip that might take up to 150 days.

On January 25, only a week after finishing the hut, Scott set out with ponies, dogs, and motor sledges to lay his caches. His plan was to drop off supplies; at intervals over a significant distance, but the weather and the poor performance of the ponies and sledges conspired against him. His last depot, named One Ton after the weight of food and fuel left there on February 17, was laid about 37 miles short of the target, latitude 80°S. This would have consequences later.

Ponies and Motor Sledges Prove Poor Choices as Scott Hears of the Norwegian Presence

An immediate problem was that seven of Scott's seventeen ponies died or had to be killed on the way back to Cape Evans. Since the motor sledges had completely broken down, this drastically reduced transportation alternatives for the upcoming polar journey.

It was also during the depot-laying journey that Scott learned from the crew of the Terra Nova what had happened to Amundsen.

His base, Framheim, had been set up just 400 miles to the east, on the margin of the Ross Ice Shelf. Amundsen seemed to have an excellent plan for his polar journey, and his men and dogs were in prime condition. Scott brooded, "above and beyond all, he can start his journey early in the season – an impossible condition with ponies."

The race was now on, whether or not Scott wished to acknowledge it as such. Much would depend on how the two teams readied themselves for the task ahead.

Winter 1911

The British Keep Busy

Scott Aims to Keep Crew Occupied

Once the depots were laid, life at Cape Evans became more routine. The scientists took their daily measurements, or conducted short fieldtrips for collecting or mapping purposes when conditions permitted. The seamen and animal handlers applied themselves to making or altering whatever was needed for the pole journey–ski boots, crampons, sledge parts, tents, and so forth.

The ponies needed special attention. Captain Oates built a stable out of provisions cases, hay bales, and other materials, with stalls and a blubber stove to keep the animals warm.

Scott was intent on keeping his crew mentally occupied and set up a heavy program of lectures, to be delivered by the scientists and officers. The subject matter of talks ranged widely, from parasitology through vulcanology to the proper management of horses.

Not everyone was thrilled to participate, but it had the effect of keeping the men's minds engaged through the otherwise little-varied days of winter.

Antarctica's Very Own Newspaper: The South Polar Times

Scott also reinstituted a project he had begun during Discovery days, The South Polar Times. The Times was a typed, single-copy newspaper-cum-magazine, all content for which was supplied by the men. Articles, poems, puzzles, and drawings were submitted anonymously to the editor, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, whose job then was to laboriously type out copy. Needless to say, some of the literary gems failed to sparkle, but it was another way to pass the time. The men played football and other rough-and-tumble games when conditions permitted. And everyone counted down the days until the sun would reappear.

June-July, 1911

Team of Three Risks Life and Limb for Penguin Eggs

Quest for Scientific Data Justifies Dangerous Trek

In June-July 1911, Wilson, Cherry, and Bowers undertook the "Winter Journey" – a 70-mile trek in the middle of the austral winter to Cape Crozier, for the sole purpose of collecting eggs of the emperor penguin. The three men suffered horrendous sledging conditions, temperatures that often sank below -60°F, and danger at every step from crevasses and blizzards. But they survived, and they got their eggs.

What could possibly have justified such a dangerous mission? The three men would have doubtless replied that scientific advancement made it worth the risk.

Wilson was convinced that the embryonic development of these penguins could solve a scientific puzzle regarding how birds and reptiles were related.

But because emperor penguins lay their eggs in the middle of the winter, there was no choice: the men had to go when they had to go. This adventure had nothing to do with showing themselves off as elite performers or going for a brass ring like the South Pole; their sole purpose was to acquire scientific data.

Years later, Cherry had this to say: "For we are a nation of shopkeepers, and no shopkeeper will look at research which does not promise him a financial return within a year... If you march your Winter Journey you will have your reward, so long as all you want is a penguin's egg."

November 1911-January 1912

The British Set Out for the South Pole

Transportation, Weather Difficulties Indicate Trouble Ahead

Scott and his men set out with 10 ponies and teams of dogs on November 1, 1911. He left later than Amundsen because he was concerned about his decrepit ponies, and hoped for slightly warmer conditions.

A motor sledge party of four had left earlier, but their machines quickly broke down and they had to continue by manhauling. The weather deteriorated in early December, with large snow falls followed by a thaw which made travel extremely difficult for both man and beast. The last of the ponies were shot, skinned, and their meat stored in a cache for later use by dogs and men. The dog teams were sent back on December 10, just before the Beardmore Glacier was reached. From now on, the 12 men headed for the polar plateau and hoped-for glory would be hauling their sledges the entire distance.

Scott Dispatches Supporting Parties Back to Camp

Working up the Beardmore was agony. Maneuvering through deep drifts and around crevasses in whirling snow, the men made painfully slow progress. In late December they topped the glacier and could now start to cross the polar plateau. Scott sent back the first supporting party of four men with the pole still more than 300 miles away. On the last day of December the two remaining sledge teams neared 87°S, which they celebrated with extra rations.

On January 4, with 180 miles to go, Scott sent back the second supporting party–but with three men rather than four. He had decided to add Birdie Bowers to his team of four (Scott, Wilson, P.O. Evans, and Oates) because he would provide extra pulling power. Scott misjudged how this last-minute change would affect both parties–one group short of haulers, the other increasingly short of supplies.

Although food was reapportioned, it now took much longer to prepare for five men, which depleted Scott's fuel stores at a greater rate. All the men were losing weight on an inadequate diet, and the temperatures were dropping steadily.

January 17, 1912

Approaching the Pole, Scott's Hopes Are Dashed

With Evidence of Norwegian Triumph, Scott Reluctantly Accepts Second Place

As late as mid-January, Scott and his men had seen no sign of the Norwegians and thought they might actually beat them to the prize. It was not to be. On January 16, Bowers saw something strange fluttering on the southern horizon. It was a black flag. This, together with ski and dog tracks told the story: The British team had come in second.

They continued on their way until their instruments told them on the next day that they had reached the South Pole. They discovered a tent – Polheim – nearby that Amundsen had left. In addition to a few discarded items, it contained a letter to the King of Norway, with a note from Amundsen asking Scott if he would be so kind as to deliver it. The British team took a few unhappy pictures to confirm their presence at 90°S, made additional observations, and started back to McMurdo on January 19.

Scott wrote, "Well, we have turned our back now on the goal of our ambition with sore feelings and must face 800 miles of solid dragging–and goodbye to most of the day-dreams!"

With Defeat Still Fresh, Scott and Crew Face a Harrowing Return Journey

For Scott and his men, a successful march home from the pole depended on decisions that had been made months ago, with virtually no room for error. Heading north in blizzard season meant that their depots would have to be located and reached in a timely manner, and Scott had not made allowance for injuries to any of his men, which would and did slow them down. They were burning more calories each day than they were consuming. In effect, they were slowly starving. Although they were still within the envelope of what passes for summer in Antarctica, they were almost 900 miles away from the safety of their base camp at Camp Evans. To get off the ice shelf before cold conditions started in earnest, Scott calculated that they had to average nearly 15 miles (33 km) a day.

February-March 1912

Injuries, Malnutrition Dog Scott's Team

Conditions Prove Fatal for Evans and Oates

On January 25, the British team reached a major depot and were able to replenish their supplies, but there was no fresh meat. It had been six weeks since they had last consumed pony meat and what little vitamin C it contained. Injuries plagued the crew and slowed progress. Wounds were slow to heal, and the workload at 10,000 feet each day was accompanied by nosebleeds, dehydration, and severe headaches. P. O. Evans's fingers were in bad shape from frostbite and a knife gash accidentally inflicted weeks before, and even Wilson and Scott were suffering from painful injuries that made man-hauling ever more difficult.

On February 4, both Scott and Evans fell into a crevasse–Evans for the second time in a few days. This time it seemed to have a serious effect on the seaman, because Scott observed he was becoming "dull and incapable." Two days later, Scott wrote in his diary that "Evans is the chief anxiety now; his cuts and wounds suppurate, his nose looks very bad, and altogether he shows considerable signs of being played out."

Evans Succumbs, Conditions Ever More Serious

Navigating the ice and crevasses of the Beardmore Glacier was difficult, as old tracks were lost and precious hours were consumed finding the way down and trying to locate depots. On February 13 Scott observed, "There is no getting away from the fact that we are not going strong." Evans's condition had been deteriorating, as Scott noted, "from bad to worse"; two days later he was "nearly broken down in brain, we think."

With 400 miles (880 km) to go, Oates pondered, "God knows how we are going to get him home. We could not possibly carry him on the sledge." A few days later, Evans dropped out of harness and shambled along behind the sledge. By noontime he had fallen far behind, causing Scott and the others to go back on skis after him. They found him on his knees, his "clothing disarranged, hands uncovered and frostbitten, and a wild look in his eyes." They had scarcely gotten him into the tent when Evans became unconscious. He died later that night. "It is a terrible thing to lose a companion in this way," Scott wrote, "but calm reflection shows that there could not have been a better ending to the terrible anxieties of the past week. Pray God we have no further setbacks."

March 1912

With Three Men Left, the End Draws Near

Scott, Bowers and Wilson Write Their Last Letters

After Oates' death the three remaining members of the polar party kept going, slower and slower as temperatures continued to plummet. Scott's right foot had become so bad that "amputation is the least I can hope for now." He could no longer pull, but at this juncture it is unlikely that the others could have done much even if they left him behind to seek help.

On March 21, Bowers and Wilson planned to set off for the next depot with the hope of bringing food and fuel back to where Scott lay. They never left. They may have been stopped by the weather, as a storm blew in. Or perhaps they were simply too weak to carry on.

Instead, they stayed in the tent and wrote their last letters. Scott, however, did much more than that. His letters display the tones of one who was stepping into his role as martyr. "I was not too old for this job," he wrote in a letter to his last commanding officer, Admiral Sir Francis Bridgeman. "It was the younger men that went under first ... We are setting a good example to our countrymen, if not by getting into a tight place, but facing it like men when we get there." In letter after letter, Scott trumpeted the courage and dignity of his fellow Englishmen, who can "still die with a bold spirit, fighting it out to the end." In letter after letter, he blamed weather, debilitation, and misfortune–but not faulty organization–as the cause of the disaster.

Scott Pens His "Message to the Public"

In his most famous missive, his "Message to the Public," Scott concluded by avowing that, "Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for."

According to Scott's last entries, they stayed in the tent for nine days and nights, unable to go farther because of the terrible weather, helplessly waiting for the weather to break as food and fuel grew less each day. They were just 12.7 miles (28 km) away from the plenitude of supplies awaiting them at One Ton Depot, but distance was now an irrelevancy.

Perhaps any unsettled weather was too much for the men to face now; perhaps in the end they preferred to die in their tent rather than in their traces.

One Final Journal Entry, and Antarctica Takes Scott and His Men

They shared what little food remained and waited for the end. Perhaps they managed to gain a little comfort from the opium pills that had been distributed earlier. "I do not think we can hope for any better thing now," Scott wrote in his last diary entry on March 29. "We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry: For God's sake look after our people."

Eventually, the tent fell silent. The winds outside continued to whip up the fine snow, coating the canvas in a thin white rime.

February 10, 1913

The British Mourn Scott's Death

Native Son Into Tragic Hero

News of Scott's death did not reach Britain until February 11, 1913. The sad facts were sent by telegraph from New Zealand, from which the Terra Nova had originally sailed in October, 1910. Cherry was amazed to see flags flying everywhere at half mast: "We landed to find the Empire – almost the civilized world – in mourning."

And indeed the outpouring of grief was remarkable. Within three days of the announcement, a state memorial service for Scott and his companions was held in St Paul's Cathedral, with, remarkably, King George V in attendance. (Reigning sovereigns almost never attended funerals or memorials of commoners.) This was the beginning of Scott's elevation to the status of tragic hero.

Hero Into Incompetent Failure

During the past several decades, however, a different picture of Scott has supplanted the heroic one – one in which he is portrayed as being staggeringly ill-prepared, thus dooming his team to dreadful failure through unsound leadership and a series of poor decisions. The arc of his reputation, from hero to bumbler, has effectively dimmed the light on Scott's contributions, not only with regard to Antarctic exploration but also to Antarctic science. By contrast, recognition of Amundsen's seemingly effortless success has only grown.

Scott Reimagined

Yet for all of his obvious, documented failings there is a full measure of countervailing evidence concerning Scott's strength of character – his sense of justice and his willingness to do anything and everything he asked his men to do.

It is just not conceivable that this man – who conducted not one but two expeditions to Antarctica and who had veterans and novices alike clamoring for positions on his team – was the blubbering, unstable incompetent that some authors have made him out to be. Scott may never receive the level of praise that Shackleton has recently enjoyed, in part because Shackleton's accolades came for him comfortably late, long after the chief participants in his expeditions had died.

Scott comes with much more baggage, and with a list of virtues that were considered exemplary in upper-class, prewar Britain, but which have little resonance today. Nevertheless, one expects that the wheel will turn again, when new attitudes take hold or old ones are reinterpreted.