Collecting Plants

Part of the Biodiversity Counts Curriculum Collection.

A plant specimen that has been properly pressed, dried, mounted on acid-free paper, and protected from moisture and insects can last for hundreds of years, Brian told us. Specimens can be stored in stacks on shelves or in cabinets, and they require very little care. The trick is to prepare them carefully and label them according to scientific conventions. If you do that, you can assemble a museum-quality botanical collection that your class, and future classes, can study and learn from.

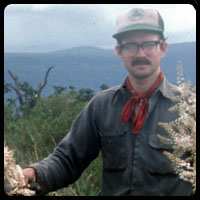

Brian has collected botanical specimens in such exotic places as the rainforests of Bolivia, but he had a lot of valuable tips for student collectors closer to home.

Collecting Tools

In addition to the identification tools (hand lens, binoculars, metric ruler, metric tape measure, altimeter, compass, and plant identification keys), Brian Boom recommended the following:

- digging tools: spade, trowel

- pruning shears

- plastic bags: various sizes to accommodate different-size specimens

- plant press, with corrugates and felt sheets

- old newspapers: for pressing specimens

- wax pencil or crayons: for marking newspapers

- field journal

- lead pencil or pen with permanent waterproof ink

- camera (optional)

- sketching materials (optional)

This is the basic kit, according to Brian Boom, though he told us about some specialized tools he uses when collecting specimens in the tropics. Typically, trees in the rainforest are very tall and do not have branches near the ground. Their foliage grows in a crown way beyond reach. Scientists use clippers on long poles, but if tree climbing is called for, they strap fearsome-looking curved spikes to their shoes or use an ingenious contraption called a tree bicycle.

Even though it is possible to put specimens in plastic bags and mount them when you get back to school, Brian recommends pressing them in the field. "Plastic bagging is okay if it's raining or if you can't press for any other reason, but it's definitely second-best. You want to press and dry your specimens as soon as possible to keep the leaves from falling off and the whole thing from rotting," he said. "You'll get the best-quality specimens by pressing in the field in newsprint and then drying with heat as soon as possible. That way the specimen is damaged less and you end up with fewer pieces of plants, which may be hard to identify. Equally important, though, you are forced to look at your specimen right then and there, instead of just tossing it into a bag to examine later. If you do that, you might think of things you should be observing while you're out in the field that you might otherwise forget about."

Brian added that one of the first and most important lessons field scientists learn is: "You can't always go back. If you don't notice certain things in the field--like odors or colors--and get them down in your field journal, you're in trouble." It is also vital to record measurements and observations about the habitat from which the specimen was taken.

"When you press and dry a specimen, you are reducing it to a two-dimensional structure, which is why observation in the field is so important," Brian said. Some scientists also take photographs or, if they have the skills, make detailed drawings of the living specimen.

Each specimen should be arranged between sheets of old newspaper. It should then be assigned a specimen number, and that number should be written in wax pencil or crayon on the newspaper as well as in the field journal. "All notes about the specimen go in the journal, but these data are useless without a corresponding number on the pressed specimen," Brian reminded us. (If you do not press in the field, put the number on the plastic bag or, if you have more than one specimen per bag, attach a label to the specimen itself.)

Numbering Specimens

When Brian Boom collected his first plant specimen in 1978, he designated it specimen 1. He still has the specimen, and he still has the field journal in which he made notes the day he collected that specimen. Now, 20 years later, he has collected more than 11,000 specimens, all numbered in the order he began with specimen 1. "These are my personal numbers, from 1 until infinity. Everything I collect will be part of that system," he explained. "I recommend that anyone who collects plant specimens start with number 1." Brian told us there are more complex numbering systems. Some people, for example, begin again at the number 1 each year, so their specimen numbers run 98.1, 98.2, and so on, with 98 standing for 1998, followed by a decimal point and the specimen number. "But I think most of the fancy systems are unnecessarily difficult to figure out," he said. "The specimen number is very important because forever, until the end of the world, that number will refer to that specimen. And as 16 or more generations of scientists study it, they will know it by that number," Brian said.

Once the specimens are dried, they should be mounted on acid-free paper and carefully labeled. They can be attached to the paper with sewing thread or white glue. Any pieces that have fallen off--fragments of leaf, bark, flowers, fruit, seeds--should be placed in a small envelope folded from another piece of acid-free paper and attached to the mounting sheet in such a way that the envelope can be opened and the fragments removed for examination.A plant press can be bought from a scientific supply house or made with easy-to-obtain materials. Once in the press, specimens must be dried quickly. Brian suggested rigging up a wooden box with lightbulbs at the bottom; the press or presses can be laid on top for a few days while the rising hot air does the job of drying. Alternatively, the press can be put on top of a radiator, but care must be taken to avoid fires. A microwave or conventional oven will not work since hot air must be allowed to circulate, carrying the moisture up and away from the specimens. "You want to dry them, not cook them," he said.

The label should include the following data, all of which you should be able to find in your field journal:

- name of your school

- name of your project

- specimen number

- specimen identification

- collection site: including city or town (if any), state, exact location (latitude and longitude), elevation, and a brief description of the habitat

- description of plant from which specimen was taken: including size, color, odor, and any other pertinent observations

- whether photos or drawings are available

- name of collector or collectors

- date specimen was collected