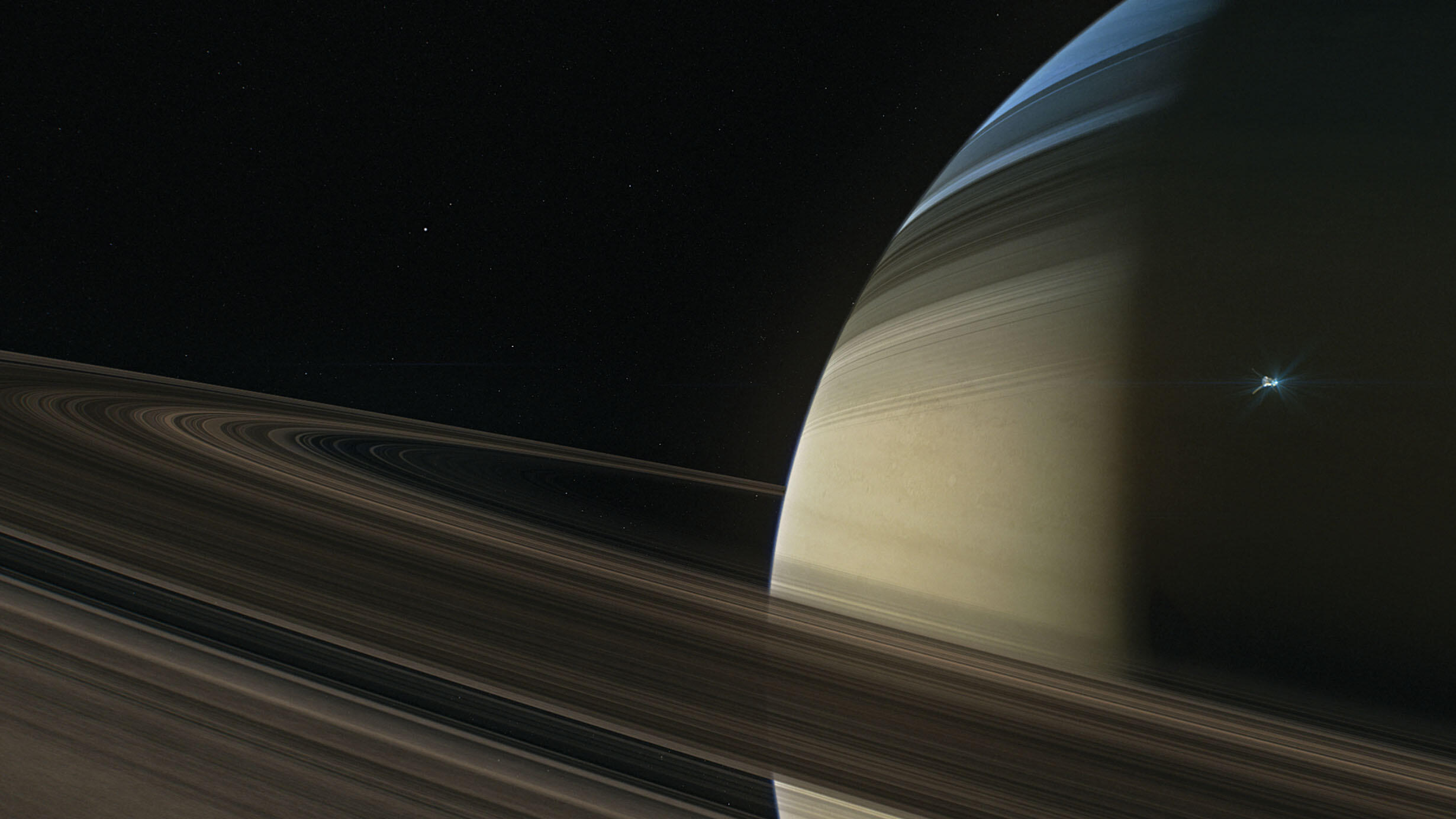

NASA’s Cassini orbiter, carrying the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Huygens probe, spent 13 years in space, during which time it captured images of Saturn and its rings in stunning detail and landed a probe on the moon Titan.

NASA’s Cassini orbiter, carrying the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Huygens probe, spent 13 years in space, during which time it captured images of Saturn and its rings in stunning detail and landed a probe on the moon Titan.NASA/JPL-Caltech

On October 15, 1997, the Cassini orbiter carrying the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Huygens probe lifted off from Cape Canaveral aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur and began a nearly seven-year journey to Saturn.

Before reaching its destination, the spacecraft completed two flybys of the brightest planet in our Earth’s sky, Venus, for gravity assists that helped accelerate its journey into the outer solar system. It passed the Earth and our Moon, whizzing by at 700 miles above the eastern South Pacific. It carved through the asteroid belt—only the seventh spacecraft to do so—and joined the Galileo spacecraft orbiting Jupiter on the other side for the first joint spacecraft study of the Jovian system. And before it ever reached Saturn, it beamed back to Earth the first of many new discoveries: two previously unknown moons—Methone and Pallene—orbiting the ringed giant.

For 13 years after its arrival at Saturn, Cassini orbited the planet, studying its magnetosphere and icy rings closely. It sent back more revelations about its sixth largest moon, confirming that Enceladus has active giant plumes that contain organic compounds and water ice fed by a subsurface ocean. Cassini also set new milestones for the exploration of alien worlds, including landing a probe on the most distant planetary body in our solar system to date—an achievement that may very well shape the future of space exploration for the next generation.

“We absolutely had to tell the extraordinary story of the Cassini mission, which gave us invaluable insights into Saturn’s entire system of worlds.”

The Cassini mission arrives in the Hayden Planetarium dome in January 2020 as one of the many spectacular stories featured in the new Space Show, Worlds Beyond Earth. Viewers will fly along with Cassini for unprecedented views of Saturn’s famous rings, which, the mission revealed, are a hot spot for studying the formation of new planetary bodies.

“We absolutely had to tell the extraordinary story of the Cassini mission, which gave us invaluable insights into Saturn’s entire system of worlds,” says Denton Ebel, curator in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, who is overseeing the new Space Show.

What Cassini Carried

Cassini was equipped with 12 scientific instruments to probe Saturn and its orbiting bodies. The suite included cameras, instruments to calculate measurements at a distance, and particle sensors to analyze magnetic fields, mass, electrical charges and densities of atomic particles, quantity and composition of dust particles, and radio waves.

Then there were the high-tech cameras: a two-part imaging system for capturing wide views as well as high-resolution images of specific details at a range of wavelengths from ultraviolet to infrared, providing valuable information for interpretation back on Earth. The stunning visualizations of Saturn are based in part on Cassini images.

Ringed Giant

The sixth planet from our Sun, Saturn was first observed through a telescope by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610. The sight perplexed him. “Saturn is not a single star, but is a composite of three,” he concluded at first, mistaking the planet’s rings for satellite bodies. (We now know that Saturn has at least 62 moons.)

It wasn’t until Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens made observations with a more advanced instrument in the 1650s that the iconic rings were described—though Huygens thought he was looking at a single, solid plane. Several decades later, Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini observed a gap—known as the Cassini division—that questioned the solid plane. By 1785, French mathematician Pierre Simon LaPlace put forward a theory that Saturn’s rings were made up of small particles.

Two centuries later, the Cassini space mission gave us an even closer look. Observations showed that the structure of the rings was far more complex than previously thought. “What the images captured by Cassini showed us were the rings at a very specific time and date. Toward the end of the mission, Cassini went up and over the rings, and was able to capture the highest resolution images of ring features resembling propellers forming as slight gravitational wakes around tiny moonlets,” says Carter Emmart, the Museum’s director of astrovisualization, who serves as director of Worlds Beyond Earth.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Those moonlets tucked into the revolving disks of ice and rock that encircle Saturn are a veritable nursery of new worlds, forming and dissipating. Some of them formed very recently, cosmically speaking—between 10 million and 100 million years ago. “Saturn’s rings are an analog for the evolution of the entire solar system,” says Ebel. “What we now know about the disc structure tells us about how solid bodies grew into larger worlds in our own early solar system, and in solar systems around young stars.”

In the new Space Show, Saturn’s rings are visualized as a dynamic crucible of planetary body formation, letting viewers glimpse a process that scientists think may be parallel to the one that led to the formation of the larger solar system.

“We can’t go back in time to watch how our solar system formed,” says Vivian Trakinski, producer of the Space Show and the Museum’s director of science visualization and producer of the new Space Show. “But the patterns we see in Saturn’s rings as the moonlets are taking shape, carving out lanes and gathering mass from debris around them, allow us to observe a similar system in formation.”

Whole New Worlds

One of Cassini’s greatest successes came in 2005, when its Huygens probe successfully navigated the thick atmosphere of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, becoming the first spacecraft to land on a moon other than our own and sending back an uninterrupted datastream of information and images of the world’s atmospheric and surface features upon descent.

“With an extraordinary effort that I still frankly can’t believe, the radio astronomers of the world…gathered together to look at the little telephone signal…coming from the other side of the solar system,” said David Southwood, director of science for the ESA, of the historic event.

See a video that highlights milestones from the Cassini mission.

What scientists have learned from Huygens’ landing surpassed every expectation. Titan’s landscape terrain is similar to Earth’s, with peaks and valleys and lakes and rivers. Its atmosphere produces weather such as rain, but instead of water, it rains methane. And its surface is strewn with seas filled with a liquified form of the greenhouse gas. It’s far too cold to be habitable by us, but its atmosphere strongly resembles what Earth was like before it evolved to host life.

“These are all our extended family of worlds that evolved in the same system alongside of us,” says Trakinski. “There’s a lot that our planet has in common with these worlds, but only Earth brings together all of the necessary ingredients and conditions that has enabled it to turn into this thriving biosphere.”

So what do Cassini’s discoveries mean for our understanding of our own solar system? For one, we’ll never look at Saturn in the same way again. “These scenes of Saturn and Titan will be delightful and fascinating to audiences,” says Carter Emmart. “We are looking at the structures in Saturn’s rings as they resemble what our models of planetary formation show us, which shows we are likely on the right track to understanding the basics of how the worlds of the solar system formed.”

Cassini has reshaped our understanding of the distant planet, which we now understand as a complex ecosystem of many orbiting bodies. The mission has also expanded our knowledge of the still-mysterious, neighboring worlds in our own solar system–and reminded us how much there is still to explore.

A version of this story appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of the Member magazine, Rotunda.