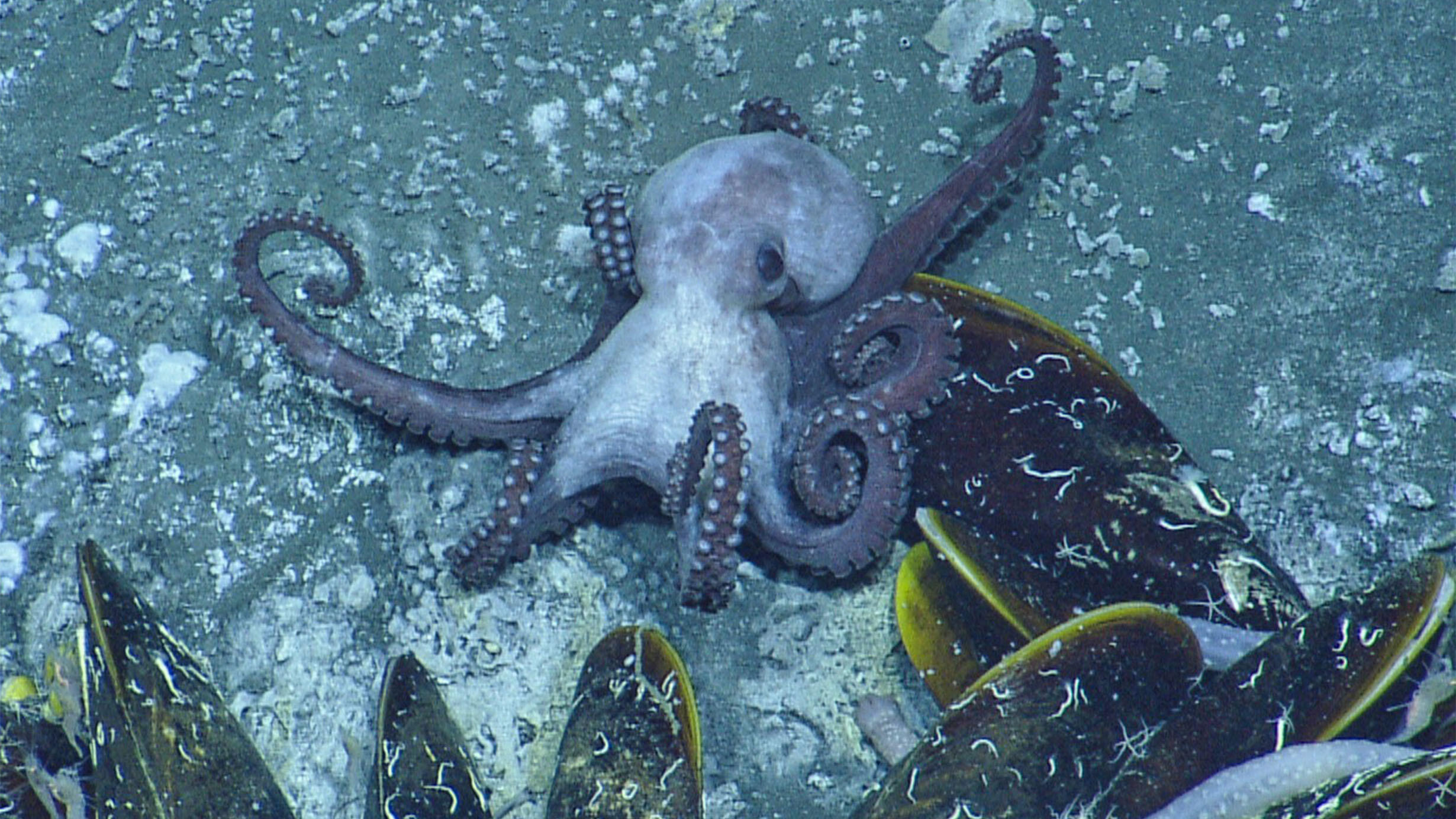

The octopus Muusoctopus johnsonianus at a modern cold seep off Grenada.

The octopus Muusoctopus johnsonianus at a modern cold seep off Grenada.Courtesy of Klompmaker & Landman (2021), with permission of Ocean Exploration Trust, Inc.

The findings suggest that a group of octopuses known to drill into the shells of their prey hunted this way as early as 75 million years ago—25 million years earlier than previously thought. The study, led by Adiël Klompmaker, curator of paleontology at the Alabama Museum of Natural History, and Neil Landman, the Museum’s curator emeritus in the Division of Paleontology, is published today in Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Octopuses from the Octopodoidea superfamily are a versatile group of marine predators with more than 200 species today. These soft-bodied cephalopods do not fossilize easily, but they leave behind a different proof of their existence: octopodoids often make tiny oval-shaped drill holes in the shells of their molluscan and crustacean prey, which they use to inject paralyzing and relaxing venom.

Some of these holes have been previously documented in the fossil record in specimens up to 50 million years old. In 2018, Klompmaker found fossils in the Museum’s collection that pushed that time frame back significantly: bivalve shells with those characteristic drill holes from the Cretaceous period.

Courtesy of Klompmaker & Landman (2021)

“I could not believe what I saw initially but, after cleaning and studying the specimens carefully later on, we became convinced that these holes are the oldest evidence of predation by octopuses,” Klompmaker said. “I was not specifically searching for holes made by octopuses, so it was a great surprise. This goes to show the importance of maintaining and exploring museum collections.”

Nearly 75 million years ago, these fossil bivalves lived in a broad seaway that covered much of North America, called the Western Interior Seaway, with a mostly featureless seafloor.

“However, methane bubbled up from the bottom in spots, forming rich diverse communities called methane cold seeps, with ammonites, sponges, starfishes, crabs, snails, sea urchins, crinoids, clams, fishes, and, as it turns out, octopuses,” Landman said.

Even though octopuses are commonly seen in today’s cold seeps, there was no previous evidence of Octopodoidea at fossil seeps. Klompmaker and Landman’s research adds a new predator to the ecosystem of ancient cold seeps.

The findings also mean Octopodoidea contributed to the rise of shell-destroying predators during what is known as the “Mesozoic Marine Revolution.” During this time, predators such as marine reptiles, teleost fishes, some sharks, and decapod crustaceans became more abundant and diverse, putting extra pressure on their prey. In response, prey including gastropods, brachiopods, and ammonites fortified their shells.

Find out more about ammonite shells in this video featuring Curator Emeritus Neil Landman.