Łingít | Tlingit

Denis Finnin/AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/2989 A,B

Selected features from the Northwest Coast Hall.

Łingít people live all along the southeastern Alaska panhandle and nearby islands, from Yakutat south to Ketchikan, and across the border into Canada. We are linked through marriage, clan relationships and oral histories.

[Still photograph of a smiling man standing on the shore of a clear blue body of water and surrounded by snow-capped mountains.]

KAA-HOO-UTCH | GARFIELD GEORGE:

Gunalchéesh awe haat yeey.aadí, aan yátx’u sáani.

Kaa-hoo-utch yóo xat duwasáakw.

Deisheetaan naax xat sitee.

Yáax’ Naa-ka hídi Deishú Hit.

Sh tóogaa ditee xwsateení.

Thank you all for coming here, people of the land.

Kaa-hoo-utch is my name.

I am Deisheetaan.

I come from Deishú Hít.

I am very grateful to see you.

Łingít Yoo Xʼatángi | Łingít Language

Łingít has been spoken for thousands of years, but since the 18th century, oppression and assimilation efforts forced people to learn English instead. As the Elder generations are aging, there are fewer and fewer speakers of Łingit. There is now a language revitalization effort, involving classes beginning in pre-school and extending through to university and continuing education. Listen to some words and phrases in Łingít, one of the languages spoken in the Łingít Nation.

Wáa sá i yatee? | How are you?

Yak’éi yee x̲wsateení | It's good to see you!

X’oon gaawx’ sáwé? | What is the time?

Shaa | Mountain

Speaker: Kaa-xoo-utch | Garfield George

Living Together

Łingít society is divided into two matrilineal groups called moieties. About half of our people are Yeił | Raven, sometimes called Crow. The rest belong to the opposite group, known as Ch’aak’ | Eagle or Wolf. Traditionally, a Raven must marry an Eagle and vice versa, though this rule is not always followed today.

© AMNH

Wolfgang Kaehler

Members of each Łingít clan inherit the right to display certain images called crests: symbolic pictures of animals, plants, celestial bodies, supernatural beings, or natural landmarks. A clan member on the Raven side, for example, may wear a hat with a Raven crest. If you are a Raven, and your grandfather is Raven, you have every right to use his crest, but only with permission.

Xaat s’áaxw | Spruce-root hat Woven of split and softened spruce root, then painted with the owner's crest, this hat was made for a high-ranking man or woman to wear during ceremonies. The design has darkened over time and some of its features are unclear, but it likely represents a raven, a crest that may be worn by people on the Raven side of Łingít society.

Xaat s’áaxw | Spruce-root hat Woven of split and softened spruce root, then painted with the owner's crest, this hat was made for a high-ranking man or woman to wear during ceremonies. The design has darkened over time and some of its features are unclear, but it likely represents a raven, a crest that may be worn by people on the Raven side of Łingít society.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/1056

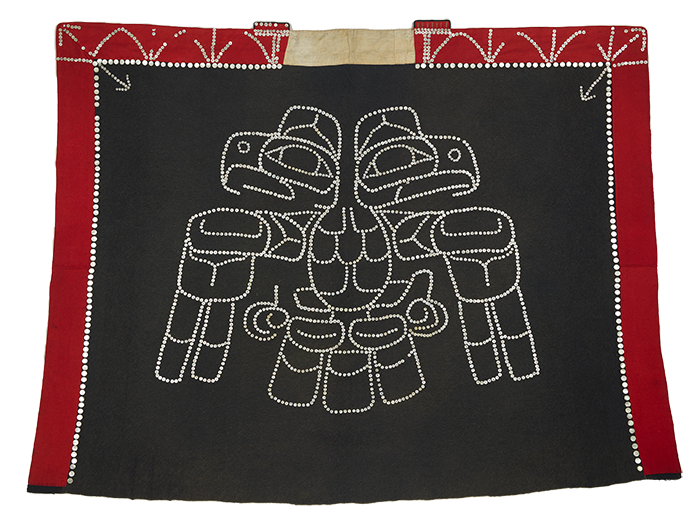

Kaayuka.óot’i x’oow | Ceremonial robe This dancing robe displays a double-headed eagle crest. This style of robe, sometimes called a button blanket, is a traditional part of Łingít life that probably dates back to the early 1800s. Before that, our people used glittering shells or rustling puffin bills to decorate robes made from animal hide, fur, or mountain goat wool. After European traders arrived in the region, artists reinvented the form, stitching mother-of-pearl buttons on ready-made cloth.

Kaayuka.óot’i x’oow | Ceremonial robe This dancing robe displays a double-headed eagle crest. This style of robe, sometimes called a button blanket, is a traditional part of Łingít life that probably dates back to the early 1800s. Before that, our people used glittering shells or rustling puffin bills to decorate robes made from animal hide, fur, or mountain goat wool. After European traders arrived in the region, artists reinvented the form, stitching mother-of-pearl buttons on ready-made cloth. AMNH Anthropology catalog E/2297

Kaséik’w | Neck ring

AMNH Anthropology catalog E/1052

Naaxein | Chilkat Robe

Denis Finnin/Anthropology catalog 16.1/1842

Made for Dancing

Using materials gathered from nature, skilled weavers on the Northwest Coast create spectacular robes with complex, curving patterns. Łingít weavers developed a style called yéil koowú | Raven’s Tail, which developed into Chilkat weaving.

The Łingít word for robes in the Chilkat style is naaxein. Images of animals are woven into the cloth, representing clan histories and connections to land, sea, and sky. People of distinction dance in these stately robes during ceremonies, and the long fringe sways as they move.

Brian Wallace, courtesy of Sealaska Heritage Institute

Raven’s Gift

A story recorded in the Chilkat Valley tells us that Chilkat weaving started near the beginning of time, when Raven traveled the world gathering knowledge. In a cave by the ocean, he encountered the powerful sea spirit Gunakadeit, who sat with a fabulous robe draped over his shoulders.

Gunakadeit served Raven a feast on long wooden dishes, taught him many dances, then gave him the robe as a parting gift. Raven brought the robe back and gave it to people, who took it apart to learn how to make robes of their own.

Click on the 3D model below for a closer look.

K’oodás’ | Chilkat tunic The boldly patterned tunic above was woven of mountain goat wool spun with cedar for an elite member of Łingít society. In the lower third of the design, two large, oval eyes and a row of black teeth make up the face of Gunakadeit.

Chilkat robes are named for Łingít weavers of the Chilkat River Valley, who became widely known for their work in the late 1800s.

Chilkat robes are named for Łingít weavers of the Chilkat River Valley, who became widely known for their work in the late 1800s.Michele Cornelius

Chilkat River Valley location.

Chilkat River Valley location.© AMNH

Images in Cloth

Chilkat weaving was developed by women on the Northwest Coast and refers to the Chilkat Łingít, who mastered the art in the 1800s and have carried it into the present. Weavers traditionally worked from patterns of rounded shapes painted on wood by a male relative. Working one section at a time, with patience and clarity, they build a design that demonstrates balance, a guiding principle in Łingít thought.

Cheryl Samuel

In the old days they had pattern boards, and then you could make templates out of birch bark. Now you can do it out of paper, or some people even use clear plastic. The advantage of the plastic is you can hold it up to your weaving and see if your lines are going where you want them to.

—Saantas’ | Lani Hotch, Weaver

Kaagwaantaan clan, Klukwan, Alaska

Daysha Eaton/KUER (left), Alaska State Library, Elbridge W. Merrill Photographs, ASL-P57-092 (top right), MOHAI, Seattle Historical Society Collection, SHS 1773 (bottom right)

Haa Atxaayí Haa Kusteeyí Sitee | Our Food Is Our Way of Life

When a Łingít clan hosts a celebration or ceremonial gathering, such as a ku.éex’ | potlatch, clan members prepare a lavish meal gathered from the sea and land. Foods such as fish, fish eggs, seaweed, game, and berries were once served in elaborate carved wooden dishes. Today, Łingít hosts use modern dishware and sometimes combine traditional foods with ingredients from Asian, European, and other cuisines.

Wild foods that thrive on the shores of Southeastern Alaska have nourished Łingít people for thousands of years.

So much of who we are and our whole identity comes from the food that we harvest from the land. Everyone looks forward to seaweed season or berry-picking season—that is something we just love doing.

—Daxootsu | Judith Ramos, Native Studies professor

Kwaashk’i Kwaan clan, Yakutat, Alaska

Respecting the Salmon People

The rhythm of Łingít life ebbs and flows with the migration of fish, especially salmon, which return to local streams to spawn annually. In the past, communities traveled together to summer fishing sites by canoe. Women fileted and dried or smoked the catch, then tied it in bales, and families paddled home in fall with boats heavily loaded. Today, many Łingít people continue to fish to feed their families, using modern or traditional boats and fishing gear.

Teresa Moses, a member of the T’akdeintaan clan, gathers herring roe collected by submerging hemlock boughs in spring.

Teresa Moses, a member of the T’akdeintaan clan, gathers herring roe collected by submerging hemlock boughs in spring.Bethany Sonsini Goodrich

Kai Monture prepares a salmon for smoking.

Kai Monture prepares a salmon for smoking.Daxootsu | Judith Ramos

S’áaxw | Ceremonial hat

This fish trap hat could open and close, perhaps representing an actual trap in one clan’s territory. “Salmon is an important part of our culture,” says Daxootsu | Judith Ramos, a Native Studies professor of the Kwaashk’i Kwaan clan, from Yakutat, Alaska. “I could see [this hat] being danced in a dance where people are singing, and then they would open the fish trap, and it would be like a transformation mask."

[Consulting Curator Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks in an interview, displaying an elaborately carved and painted hat in the shape of a woven fish trap.]

DAX̲OOTSU | JUDITH RAMOS (Consulting Curator): I really think this is a beautiful headpiece here.

[On-screen text reads, “Sáaxw, Ceremonial Fish Trap Hat.”]

RAMOS: And one of the things I love is the beautiful painting and colors.

[Photo of Dax̲ootsu in ceremonial regalia with text reading “Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos, Kwáashk’ikwáan Clan, Yaakwdáat Kwáan, Tlingit”]

[Image of a young man smiling in front of dozens of strips of drying salmon.]

RAMOS: Salmon is so much an important part of our culture. This is a representation of a fish trap.

[Ramos displays the fish trap hat. Text reads, “Sháal | Fish trap.”]

[Salmon swimming in shallow water.]

RAMOS: We had many different technologies for harvesting fish up but this one the fish would come in and then it'll get trapped in there and won't be able to come out.

[Front view of the sáaxw fish trap hat. A human-like face tops the hat.]

RAMOS: It's very sculptural and I could see it being danced in a dance where people are singing and then they would open the fish trap.

[Ramos speaks to camera.]

RAMOS: So much of who we are comes from the food that we harvest from the land.

[Majestic mountains tower over a green landscape.]

RAMOS: I enjoy going out and harvesting medicine,

[Lacy, delicate flowers next to text reading “Kagakl’eedí | Yarrow (Medicinal).”]

RAMOS: …plants, salmon, and everything.

[A salmon, deep red in breeding season with text reading “Gaat | Sockeye salmon.”]

[Leafy seaweed next to text reading “K’áach’ | Ribbon seaweed.”]

RAMOS: Everyone looks forward to seaweed season or berry-picking season.

[Blueberries next to text reading, “Kanat’á | Blueberries.”]

RAMOS: That is so much something we just love doing.

[Image of the Sáaxw, Ceremonial Fish Trap Hat on display in the Northwest Coast Hall.]

Yakutat Seal Camp Project

The Yakutat Seal Camp Project combined archaeology, geology, oral history, and traditional ecological knowledge. Funded by the National Science Foundation, this was a collaborative research project with the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center. In the video below, scholar Daxootsu | Judith Ramos discusses how the multidisciplinary study combined stories shared by Elders with archaeology to uncover the past.

YAKUTAT SEAL CAMP PROJECT

[Native Studies professor Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks to camera in an interview setting.]

DAX̲OOTSU | JUDITH RAMOS (Native Studies Professor, Kwaashk’I Kwaan Clan): In our oral history, my people were originally from the interior and we migrated down to the coast.

[Aerial views of glacial landscape—snow covered mountains, sweeping clouds, rugged, icy surface of glaciers.]

And when we came to Yakutat Bay, the Hubbard Glacier and Malaspina [Glacier] were one glacier.

[Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks to camera.]

My history is based on combining Indigenous knowledge with the scientific knowledge. So, we documented knowledge through oral history from Elders,

[An Elder speaks with an interviewer outdoors.]

…looking at traditional place names,

[In a leafy, outdoors setting, a group of people stand around a seated Elder with raised hands. A younger person beats a drum.]

[A man standing amidst a roped-off grid points to something on an archaeological dig site.]

…and also, we spent a couple of summers just doing archaeological digs,

[An archival black and white image of a group of people on a shore with tents in the background and a boat in the foreground.]

…and trying to locate some of the ancient seal camps through archaeology.

[Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks to camera.]

And a geologist looked at a couple of sites to try and date the glacier advances at certain points within the last thousand years.

[A man with binoculars stands on an icy shoreline and points out to the horizon.]

[Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks to camera.]

A lot of my research is also looking at traditional seal hunting…

[Illustration of hunters in boats, with one man in the prow preparing to throw a long harpoon-like spear at a seal.]

…because it's a way of life that's changing, has changed since my grandparents' time.

[Archival color photo of a hunter in a boat with rifles, surrounded by icy waters.]

We don't hunt as much as we did in the past.

[An Elder indicates something on a large map to Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos.]

So, we [are] documenting Elders' knowledge on traditional seal hunting…

[Contemporary hunters on a boat in icy waters. A young man holds a rifle. Crawling across the ice, a seal dives into the water.]

…and their knowledge of the environment—how they used to hunt in the ice, different terminology for seals, and how we processed seals, and what we used with the different products.

[Dax̲ootsu | Judith Ramos speaks to camera.]

And one of the most important products is the seal oil, which was used for a preservative for all our foods.

Haa Ḵusteeyí | Our Way of Life

Some of the foods described above may be served during a ceremony we call a ku.éex’ | potlatch, a time for public speaking, singing, dancing, feasting, and distributing gifts. A Łingít clan may host a ku.éex’ to recognize a child’s coming of age, a marriage, a house renovation, or—more often—a family loss. Through words and actions during the ceremony, hosts and guests reinforce the Łingít philosophy of balance and respect for one another.

Daxootsu | Judith Ramos

Daxootsu | Judith Ramos

Daxootsu | Judith Ramos

ku.éex’ | inviting people A traditional ceremony hosted by a Łingít clan, informally called a party or potlatch.

Then and Now: Centennial Potlatch

Guests from Angoon, Alaska, attending a ku.éex in Sitka in 1904.

Guests from Angoon, Alaska, attending a ku.éex in Sitka in 1904.Alaska State Library, Elbridge W. Merrill Photograph Collection, PCA 57-28

In 2004, the Centennial Potlatch was held in Sitka, Alaska to commemorate the one held 100 years before.

In 2004, the Centennial Potlatch was held in Sitka, Alaska to commemorate the one held 100 years before.Robert W. Preucel

History Songs

Kaa-xoo-utch | Garfield George talks about history songs and sings one with his daughter during the opening of the Northwest Coast Hall in 2022.

[SINGING AND DRUMMING]

[A man in ornate regalia—a headpiece decorated with iridescent shell pieces and a beautiful, long blanket—drums and sings. Next to him a girl wearing a cloak embellished with buttons and a woven cedar hat with a tall, fin-like attachment at its crest moves slowly around. Her hands are held out, open. They are in the Northwest Coast Hall at the American Museum of Natural History, surrounded by display cases.]

KAA-HOO-UTCH | GARFIELD GEORGE (House Master, Deishú Hít, Deisheetaan Clan, Łingít): My daughter sings- I tell my daughter all the history, you know.

[Kaa-hoo-utch | Garfield George speaks to an off-camera interviewer.]

KAA-HOO-UTCH | GARFIELD GEORGE: Every night I tell her history. Her own history of my Dad’s people. And I sing to her. And she can sing. Even when she was two years old, she would sing with me.

So, I keep telling her, I said, you can’t forget this kind of stuff. Even if you never spend any time in Alaska, you gotta at least know who your Ancestors are on your Dad’s side.

[Kaa-hoo-utch | Garfield George stands next to his daughter, both wearing ceremonial regalia. Text identifies this as “Opening Ceremonies, Northwest Coast Hall, May 2022.”]

KAA-HOO-UTCH | GARFIELD GEORGE: And to remember that history, they composed Kéet Gaaw, the Killer Whale Drum song.

[Kaa-hoo-utch | Garfield George and his daughter sing and dance a history song in the Museum Hall.]

A Village Attacked

In 1882, Til’xtlein, a traditional doctor from Angoon, Alaska, died in an accident on a commercial whaling boat. Following custom, the rest of the Łingít crew stopped work to mourn, halting the vessel and seeking compensation for their loss. A local official feared the Łingít people were planning an attack and asked the U.S. Navy to intervene. The Navy sent two armed ships into the waters off Angoon. The commander delivered an ultimatum that the Łingít people could not meet. Then he ordered the sailors to bombard the village. Six children were killed, and most of the houses, canoes, and food supplies were destroyed.

Alaska State Library, Vincent Soboleff Photograph Collection, ASL-P1-083

One canoe remained, which the community relied on to harvest food to survive the winter. The prow was fitted with a carved beaver, a crest of the Deisheetaan Clan. Centuries ago, Ancestors of the Deisheetaan Clan followed a beaver trail to a beach, where they founded the village of Angoon. To this day, Beaver is a Deisheetaan crest.

After the savior canoe was no longer seaworthy, it was cremated as a person. Eventually, the Beaver Prow was sold to this Museum with very little information. After a Łingít delegation discovered it in the Museum’s collection in 1999, it was formally repatriated, or returned, to the Angoon villagers in an emotional reunion.

Kaa-xoo-utch | Garfield George

In 2020 Deisheetaan member Yéilnaawú | Joseph Zuboff carved a likeness of the beaver to be displayed in the renovated Northwest Coast Hall, as seen below. The original is kept as a clan treasure in Angoon.

The original Beaver Prow, seen here with the likeness carved in 2020 for the Northwest Coast Hall.

The original Beaver Prow, seen here with the likeness carved in 2020 for the Northwest Coast Hall.Yéilnaawú | Cyril J. Zuboff

The likeness of the Beaver Prow, shown in Northwest Coast Hall.

The likeness of the Beaver Prow, shown in Northwest Coast Hall.Denis Finnin/© AMNH

Here is a behind-the-scenes look at Yéilnaawú’s carving process.

Beaver Prow Shadow Carving

[Yéilnaawú | Joseph Zuboff shapes a piece of wood with a chisel in his workshop. The wood has a similar form to a finished carved and painted beaver that sits nearby.]

[Jump cuts illustrate Yéilnaawú’s progress as he works with different tools.]

[Yéilnaawú continues to shape the piece of wood, sometimes in big chunks and sometimes using finer shaping tools.]

More Resources

Łingít Consulting Curators

Daxootsu | Judith Ramos, Kwáashk’ikwáan Clan, Yaakwdáat Kwáan

Kaa-hoo-utch | Garfield George, House Master, Deishú Hít, Deisheetaan Clan

The Museum thanks X’unei | Lance Twitchell, Kingeistí | David Katzeek, and the Łingít community for the Łingít words included in this text.