Educator Resources: Northwest Coast Hall

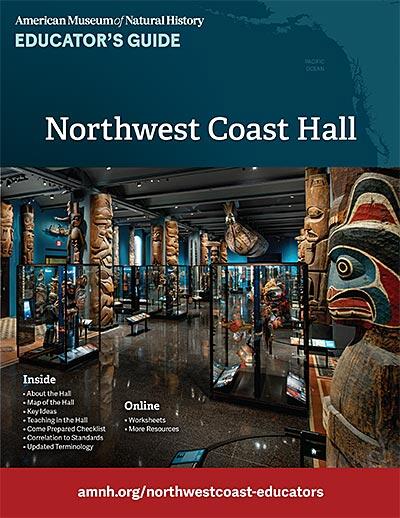

Part of Northwest Coast Hall.

Northwest Coast Hall of Educator's Guide

Get an advanced look at the hall's major themes and what your class will encounter. This 8-page guide for K-12 educators includes a Map of the Hall, Key Ideas (important background content), Teaching in the Hall (self-guided explorations), a Come Prepared Checklist, Correlation to Standards, and Updated Terminology.

Activities and Materials

Grades K–5

Using worksheets in the hall, students observe and talk about four Indigenous treasures. They will learn to recognize the basic shapes of an Indigenous art tradition called Formline, as well as learn about the stories that cultural treasures tell about the people who made them.

Grades 6–12

Using worksheets in the hall, students explore the cultural and scientific practices and understandings that have developed in the Indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest over thousands of years and continue today.

Living Cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast

People of many Native Nations live along the Northwest Coast of North America, where home is the seas, the mountains, the rivers and forests, the small towns and large cities along the Pacific Coast.

Geography

Download this map to see the locations of the 10 Native Nations featured in the hall.

• Regional Map of the Northwest Coast: PDF | PowerPoint

Pronunciations

Click on the links below to listen to the names of the 10 Native Nations featured in the hall. These audio resources, featuring the voices of Native people of those communities, are also located in the multimedia kiosks throughout the hall.

Coast Salish

Gitxsan

Haida

Haíɫzaqv

Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw

Nisg̱a’a

Nuu-chah-nulth

Nuxalk

Łingít | Tlingit

Tsimshian

Voices of the Native Northwest Coast

Watch this 11-minute video to hear Indigenous experts discuss the histories, persistence, and present concerns of the Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. This video by Tahltan/Gitxsan filmmaker Michael Bourquin can also be viewed in the introductory theater in the hall.

[The sun rises over the ocean as waves lap at the beach next to a hill covered in trees.]

KIL GAL TSEETKIS – CHEYENNE MORGAN (GITXSAN): When I think about the Northwest Coast I always think about the diversity in cultures, in governance structures, in languages.

[A monumental carving (“totem pole”) is dusted with snow with a snow-covered mountain in the distance.]

KIL GAL TSEETKIS – CHEYENNE MORGAN: A lot of people think it’s kind of all the same culture up here, totem poles and canoes…

[A group of people wearing cedar-bark woven hats steer a canoe with paddles painted with Indigenous Northwest Coast designs.]

KIL GAL TSEETKIS – CHEYENNE MORGAN: …and it’s extremely diverse.

[A map of North America appears on screen with a white box around the area of the Northwest Coast, which stretches from northern Washington state, through British Colombia, and into southern Alaska along the coast of the Pacific Ocean.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY (HAÍⱢZAQV): I think the history of the West Coast First Nations is long and complicated and there’s a lot more to our history than what you would read in a book.

[SINGING]

[At a potlatch community celebration, a large group of people wearing Native Northwest Coast dress sing together.]

KEIXÉ YAXTÍ – MAKA MONTURE PÄKI (TLINGIT): And I feel fortunate the I grew up in a culture…

[Closeup of a woman wearing a headdress and regalia at a community celebration.]

KEIXÉ YAXTÍ – MAKA MONTURE PÄKI: …where a woman’s voice was inherent…

[Keixé Yaxtí – Maka Monture Päki speaks to camera in the Museum’s Anthropology Conservation lab, sitting next to her mother Daxootsu – Judith Ramos.]

KEIXÉ YAXTÍ – MAKA MONTURE PÄKI: …and their power was inherent.

[A group of women in regalia release eagle down at a community event.]

[Consulting Curator of the Northwest Coast Hall Daxootsu – Judith Ramos speaks to camera next to her daughter Keixé Yaxtí – Maka Monture Päki]

DAXOOTSU – JUDITH RAMOS (TLINGIT): So we’re very much a very strong matrilineal-based culture, so we convey our lineage on to our children.

[Footage of the Pacific Northwest Coast landscape: an aerial view of water lapping against a tree-covered cliff, a forest of cedar trees in dappled sunlight]

SM ŁOODM 'NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI (TSIMSHIAN): Our way of life as a people and our people ourselves, we’re born of the land.

[An eagle soars through the sky on a cloudy day.]

[Sm Łoodm 'Nüüsm – Dr. Mique’l Dangeli speaks to camera in front of a background painted with Indigenous Northwest Coast designs, wearing a woven hat and abalone necklace in the shape of a copper.]

SM ŁOODM ‘NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI: It’s a reciprocal, symbiotic relationship that has created our language.

[Beams of sunlight breaks through heavy fog rolling over a forest of evergreen trees.]

ḤAA’YUUPS (NUU-CHAH-NULTH): Kuukwaḥulth, ‘Tlitsaaḥuulth, Na’mint…

[Co-Curator of the Northwest Coast Hall Ḥaa’yuups speaks to camera in front of a large bookshelf with a carved and painted mask visible.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: …Tluushtluushuk, Aḳmaḳuulth. All of those Mountains have names.

[Drone shot flying over the snowy peaks of mountains along a river.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: We have songs, we have personal names that come from those places.

[Drone shot flying over rocky mountain peaks that reach above a layer of clouds.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: We have ceremonies that have to do with those places.

[Eagle’s-eye-view of waves lapping against a cliff covered in trees and green growth.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO (NUXALK): They say when the First Ancestors came down from the upper world…

[Beams of golden sunlight stream into a dense, moss-coated forest through gaps in the trees’ branches.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: …they learnt the land and they began to prosper.

[Consulting Curator for the Northwest Coast Hall Snxakila – Clyde Tallio speaks to camera from the Museum’s Anthropology conservation lab.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: They prospered so much that their houses became stacked with goods. Many of those goods would spoil before they could be used. It was being wasteful.

[Close-up of a large wooden carving, accented with bright red, blue, and green paint.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: And so the Creator, He spoke to all the people.

[At a celebration, a dancer in regalia uses strings to move the eyes and mouth of a carved and painted wooden mask he wears.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: He said to Lhlm.

[In the big house of the HaíⱢzaqv community, a man throws a log onto an already large fire, causing sparks to fly upwards. A wide shot of the big house full of community members in button blankets, headdresses, and other regalia.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: He said, “Invite your neighbors from far and near. Invite them to your house.

[A line of women wearing cedar bark hats and aprons with a Native Northwest Coast design prepare plates of food at a community event.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: Feast them.

[Closeup of a dancer wearing a carved wooden mask painted in black and red.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: Share your wealth with them.

[A community member speaks to a crowd in the HaíⱢzaqv Big House; two women blow eagle down on either side of a dancer opening a transformation.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: Tell your stories on how I put you here,” the Creator said.

[A line of women in the HaíⱢzaqv Big House sing in front of a fire with their hands raised.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: And that’s the origin of potlatch. The entire coast practices potlatch.

[Consulting Curator for the Northwest Coast Hall, Niis Bupts’aan – David Boxley, speaks to camera in the Museum’s Anthropology collection storage space.]

NIIS BUPTS’AAN – DAVID BOXLEY (TSIMSHIAN): Well, for one thing, it was the hub of our social and political wheel.

[Put’ladi – Kerri Dick speaks to camera.]

PUT’LADI – KERRI DICK (HAIDA KWAGU’Ł): It’s our identity.

[Several shots of dancers and singers participating in songs and dances during potlatches, wearing many types of regalia.]

PUT’LADI – KERRI DICK: It’s how we named our children. It’s how we married. It’s how we buried people. That’s how we passed our lineage on. That’s how we passed our dances on.

[Consulting Curator for the Northwest Coast Hall, Kaa-Hoo-Utch – Garfield George, speaks to camera wearing a jacket with a Native Northwest Coast button design.]

KAA-HOO-UTCH – GARFIELD GEORGE (TLINGIT): Because, you know, our songs are not generic, they’re history songs. The main events that happened to us became songs.

[At a potlatch, smiling participants dance in a circle while a drum is played. Others look on from seats, smiling and taking photographs.]

CHIEF GA’LASTAWIKW – TREVOR ISAAC (KWAKWAKA’WAKW): During a potlatch, you invite guests…

[A group of young people hands out gifts to guests at a potlatch. A woman in a cedar bark hat serves a bowl of food to a guest.]

CHIEF GA’LASTAWIKW – TREVOR ISAAC: who you then pay as witnesses.

[Consulting Curator for the Northwest Coast Hall Chief Ga’lastawikw – Trevor Isaac speaks to camera.]

CHIEF GA’LASTAWIKW – TREVOR ISAAC: By them accepting the gift, they’re agreeing to remember everything that has happened during that ceremony.

[A tall monumental carving (“totem pole”) stands in a forest surrounded by living trees of the same height.]

CHIEF 7IDANSUU JAMES HART (HAIDA): So there is deep history…

[Aerial view of lush green trees on a cliff along the coastline.]

CHIEF 7IDANSUU JAMES HART: …roots here with family and clan and stuff, because this is our lands.

[Chief 7idansuu James Hart speaks to camera.]

We didn’t come here from somewhere else, you know, and this is it.

[An old canoe with grass growing through its bottom rests near a beach, bathed in the golden light of the setting sun.]

CHIEF IAN CAMPBELL – SEKYU SIYAM (SQUAMISH): I would say that the early settlers arrived…

[Chief Ian Campbell – Sekyu Siyam speaks to camera.]

CHIEF IAN CAMPBELL – SEKYU SIYAM: …in the idea of Doctrine of Discovery, or terra nullius, that this is a free and vacant land to be claimed.

[The sea rushes into and crashes along crags where a rocky cliff meets the coast line.]

[Secəlenəχʷ – Morgan Guerin speaks to camera.]

SECƏLENƏΧʷ – MORGAN GUERIN (MUSQUEAM): The first time European faces saw who we were in the late 1700s here in my territory…

[Drone shot flying above small islands covered in green trees surrounded by deep blue water.]

SECƏLENƏΧʷ – MORGAN GUERIN: …we had already been decimated in numbers, and we hadn’t even seen the second wave of smallpox yet.

[Drone shots flying above a large, rocky island covered in green evergreen trees surrounded by clear water that becomes darker further from the island.]

CHIEF 7IDANSUU JAMES HART: We had villages all around the lands here, all around the shores. What kept us here is the food, lots of sea foods…

[Salmon swim gently against the current in shallow water.]

CHIEF 7IDANSUU JAMES HART: …and bountiful that way, you know…

[Chief 7idansuu James Hart speaks to camera.]

CHIEF 7IDANSUU JAMES HART: ...and through time, we learned how to farm the seas and so we wouldn’t overtake.

[An eagle soars over sparkling blue water.]

[Lihl Ka Jaad Kinas Candace Weir-White speaks to camera, with several wooden carvings visible in the background.]

LIHL KA JAAD KINAS CANDACE WEIR-WHITE (HAIDA): One of our Elders, one of our late Elders, he said if we take care of the land, the land will take care of us.

[GwaaGanad Diane Brown walks arm-in-arm with a young woman while looking out at the landscape.]

GwaaGanad DIANE BROWN (HAIDA): We are so tied into the land.

[GwaaGanad Diane Brown speaks to camera.]

GwaaGanad DIANE BROWN: That’s what makes us different.

[Drone shot flying through a cedar forest with grass waving in the wind.]

SECƏLENƏΧʷ – MORGAN GUERIN: Wherever there was a First Nation, we’re always living with Mother Earth, and we’re always around those hubs of resources.

[Indigenous Northwest Coast community members harvest kelp and herring roe from a boat.]

Of course, those same things were then considered a commodity by our settlers moving and living with us.

[Wide shot of tree-covered mountains rising out of the sea with clouds reflecting the orange glow of the sun.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: And so when they came in, they came in with a whole different mindset on resource use and resource extraction.

[Dúqva̓ísḷa – William Housty speaks to camera.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: It was based on a similar sort of thing that we see in this day and age, where more is better.

[Aerial view of waters in the Northwest Coast, many shades of blues and greens are visible in the water, suggesting presence of fish and sea plants. Underwater shot of an enormous school of fish swimming near the surface.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: And when I was a boy, we saw fish in numbers people can't even imagine today. In my lifetime I've seen that change.

[Historic black-and-white photograph of Indigenous Pacific Northwest fishermen standing in front of the day’s catch—about two dozen.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: Well I mean you look at the first nations people on the coast and the way we all manage the salmon systems for at least 14,000 years…

[Underwater shot of salmon swimming toward the camera.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: …we never had a crash.

[Historic black-and-white photograph of an industrial fishing facility with thousands of harvested salmon waiting to be processed.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: And so when you look at how salmon has been harvested over the last 40 or 50 years managed by the government…

[Aerial footage looking down at industrial fishing boats.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: …we don't have any more salmon. And we're salmon people.

[The camera looks up at tall trees in a forest, many with moss growing along the trunks.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: The forest of this island I said, somewhere upwards of 90% has been logged.

[Series of shots showing where industrial logging has left large patches of forests empty and baren.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: So it's been denuded.

[Slow aerial shot flying along a dense forest.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: But there was a point in time where the government mandated everybody to have a hand-log license.

You had to be on the voters list to be able to get a hand-log license, and Indians weren't allowed to vote, so our people weren't allowed to log, weren't allowed to take trees from our own territory.

[Chief Ian Campbell – Sekyu Siyam speaks to camera.]

CHIEF IAN CAMPBELL – SEKYU SIYAM: So this great distortion to marginalize and oppress indigenous peoples through legislative oppression directly stems from this “gold rush” mentality, the modus operandi for others to become affluent at indigenous peoples’ expense.

[Dúqva̓ísḷa – William Housty speaks to camera.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: Yeah, systemic racism has been present here amongst all the coastal tribes since the first contact with the white people. It's persisted right into the current moment that we're having this conversation.

[Closeup of face carved into a wooden monumental carving (“totem pole.”)]

SM ŁOODM ‘NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI: So from 1884 to 1951…

[Closeup of hands weaving and then examining the pattern on a woven Chilkat blanket.]

SM ŁOODM ‘NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI: …our cultural practices on the Northwest Coast were criminalized…

[An Indigenous carver uses a metal tool to carve a piece of wood in her studio.]

SM ŁOODM ‘NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI: …through a law called the Potlatch Ban.

[Sm Łoodm 'Nüüsm – Dr. Mique’l Dangeli dances in regalia with a rattle and spreads eagle down from her headdress at a potlatch.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: So if anyone, a chief was to give gifts to the people…

[Dancers in masks, cedar bark hats, woven blankets, and other regalia perform at a potlatch.]

SNXAKILA – CLYDE TALLIO: …he was to support his people in any way, that staltmc could be put in jail.

[Sgaan Kwahagang James D. Mcguire speaks to camera and shows the back of his hand, revealing a large tattoo of an Indigenous Northwest Coast design.]

SGaan KWAHAGANG JAMES D. MCGUIRE (HAIDA): Having this tattoo on my hand was illegal. These were acts of savagery, having long hair, speaking your language.

GwaaGanad DIANE BROWN: So we kept our chiefs by having underground namings and potlatches. Mainly that.

SM ŁOODM ‘NÜÜSM – DR. MIQUE’L DANGELI: 1951 is when that law was dropped, and that's not very long ago. That's within my… my mom was born before 1951.

[Fog almost completely obscures a line of tall evergreen trees.]

CHIEF WÍGVIŁBA-WÁKAS – HARVEY HUMCHITT (HAIŁZAQV): They installed fear into our people.

[Historic black-and-white photograph of Indigenous children at a residential school.]

CHIEF WÍGVIŁBA-WÁKAS – HARVEY HUMCHITT: I guess that's how they managed to apprehend or take young kids away from their homes and put them into residential schools.

[Black-and-white photograph of a large European-style building. Text on screen reads, “COQUALAETZA INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL.”]

GOOTHL TS’IMILX – MIKE DANGELI (NISGA’A, TSETSAUT, TSIMSHIAN, TLINGIT): So my grandfather was lured by an Indian agent…

[Goothl Ts’imilx – Mike Dangeli speaks to camera.]

GOOTHL TS’IMILX – MIKE DANGELI: …lured on a boat with candy and sent to Coqualaetza in Chilliwack. Like his family didn't know where the heck he was.

[Put’ladi – Kerri Dick speaks to camera.]

PUT’LADI – KERRI DICK: If you tried to go get your children, if you tried to keep them away, you were thrown in jail just as quickly as anybody who potlatched.

[Kwankwanxwaligedzi – Wakas | Robert Joseph, Hereditary Chief speaks to camera.]

KWANKWANXWALIGEDZI – WAKAS | ROBERT JOSEPH, HEREDITARY CHIEF (GWAWA’ENUXW): The most hurtful, damaging result of residential schools was dehumanizing little, little kids.

[Ḥaa’yuups speaks to camera.]

ḤAA’YUUPS: And certainly our last two centuries of experience in this country has been massively affected by their racism.

[Fog swirls quickly around a rocky mountaintop.]

JISGANG NIKA COLLISON (HAIDA): Western people, settlers, they don't need to be afraid to look back. They need to look back just to understand the history…

[Consulting Curator for the Northwest Coast Hall Jisgang Nika Collison speaks to camera from the American Museum of Natural History, with treasures laid on the table next to her.]

JISGANG NIKA COLLISON: …understand what modern North America is built upon, hey?

[The camera flies around a large rock positioned on a rocky beach with glistening water and mountains visible in the background.]

JISGANG NIKA COLLISON: So many ways we survived, and also by not giving up our lands or waters, ever.

No one in the colonial world has a record of us giving up our land, because we never did. It's ours.

[Chief Ian Campbell – Sekyu Siyam and others paddle a canoe painted with Indigenous Northwest Coast designs and flying a flag in the waters in front of a major city skyline.]

CHIEF IAN CAMPBELL – SEKYU SIYAM: I think to this day, many people still have a preconceived image that “oh, there's a reserve somewhere over there on the outskirts of our town,” and they forget to acknowledge that the entire area that they live in is in our traditional territory, and that we've been marginalized onto the these reserves through colonialism.

[Put’ladi – Kerri Dick weaves on a wooden device.]

PUT’LADI – KERRI DICK: Nothing in this world can deplete who you are. They stopped us from speaking.

[A small child in regalia beats on a drum at a potlatch. Wide shot of a group clapping during a potlatch, including two Royal Canadian Mounted Police.]

PUT’LADI – KERRI DICK: They took our children away. They stopped us from potlatching, and yet we still potlatch. We still sing. We still teach our children how to speak, and there's nothing in this world that was going to stop us from being who we are.

KIL GAL TSEETKIS – CHEYENNE MORGAN: My daughter's name is Skiltuu, and before she was born, I made a commitment that I would be speaking Sm’algyax to her as much as possible.

[Skiltuu Bulpitt, a very young girl, sits on her mother’s lap holding a stuffed animal. She smiles as she repeats the words in Sm’algyax that her mother speaks to her.]

SKILTUU BULPITT (GITXSAN – HAIDA): [Speaking Sm’algyax] Chiefs…matriarchs…and noble descendants. My heart is very full…when I use Sm’algyax. I thank all the chiefs. That is all.

[Kil Gal Tseetkis – Cheyenne Morgan speaks to camera.]

KIL GAL TSEETKIS – CHEYENNE MORGAN: When I see my daughter speaking Sm’algyax, I feel so full, lits’eex goot’t, your heart is just so full.

[A dancer wearing a Chilkat robe and headdress spins in slow motion at a potlatch.]

[A carver uses a metal tool on a carving in progress.]

XSIM GANAA’W – LAUREL SMITH WILSON (GITXSAN): We're a living culture. This is not a history that once was, that somehow faded away never to be heard of other than in museum spaces.

[A dancer with a raven headdress pulls a string so that the beak opens and closes rapidly during a potlatch.]

SECƏLENƏΧʷ – MORGAN GUERIN: We are not going anywhere. Nor should we have to.

Never again will we not be proud of who we are.

[Aerial view of HaíⱢzaqv community’s Big House, Gvakva'aus HaíⱢzaqv or “House of the HaíⱢzaqv.” HaíⱢzaqv elders in full regalia and headdresses enter. Inside, HaíⱢzaqv community members participate in a potlatch.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: My generation is the first generation in our community that can walk into this building, participate in a potlatch, and not have to worry about anything.

My mother's generation, my grandfather's generation, the ones before them couldn't do it. Weren't allowed.

[Dúqva̓ísḷa – William Housty speaks into a microphone at a potlatch in the big house next to brightly painted wooden carvings.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: But I could walk in here free. My kids could walk in here free.

[Slow motion shot of dancers dancing around the fire pit in the big house. HaíⱢzaqv elders and HaíⱢzaqv children dance and participate in the celebration.]

DÚQVA̓ÍSḶA – WILLIAM HOUSTY: And now, with what's left from the older generations, we're learning, we're building, we're instilling those customs back into the younger generations through language, through traditional ceremonies, and one day if we continue to do that, we'll be right back where we were when we were tens of thousands of Hailtzsuk people using our language on everyday basis, practicing our culture freely, not worrying about who's going to walk through those doors and tell us we can't do it. Those days are gone.

[Fade to black.]

[Credits.]

Updated Terminology

In consultation with Native communities, the renovated hall has corrected names and terminology, including:

- Indigenous or Native communities, peoples, or Nations are used to refer to the communities whose histories, cultures, and works are featured in this hall. Some communities are in the U.S. (Alaska and Washington State) and others in Canada, referred to as First Nations.

- Monumental Carvings are the name for the large wooden carvings in the hall (also known as totem poles). Cultural treasures, collections pieces, and objects are terms that can be used to describe what’s exhibited in this hall.

- Names and labels in the new hall text have been updated in consultation with Consulting Curators and include words in Indigenous languages as well as in English.

Additional Resources

Basketry: Woven Traditions

Museum conservators travel to the forests and marshes of Suquamish, Washington, to learn about Native Northwest Coast basket weaving from master weaver Ed Carriere.

Northwest Coast Basketry—Woven Traditions

[AMBIENT FOREST SOUNDS AND BIRD CALLS]

[Short video clips cycle showing Ed Carriere picking up a branch from the forest floor surrounded by cedar trees, using a knife to peel some bark from a cedar limb, digging amongst tall grasses.]

ED CARRIERE (Suquamish Elder and Master Basket Weaver) [Voice Over]: I come from the Suquamish reservation. Suquamish Washington. A little town of Indianola.

[A black-and-white of Julia Jacobs, Ed Carriere’s great grandmother, appears.]

CARRIERE: My great grandma, she was the one that wove these really beautiful clam baskets for the tribal clam diggers.

[Ed harvests tall grasses, pulls strips of inner bark from a fallen cherry tree, uses a knife to peel away layers of bark, and folds up a thin strip of cherry bark.]

CARRIERE: And so I would watch her when I was little. When I got about 14 years old, I got brave enough to make my own clam basket. That led me into basket weaving.

[Ed cuts down tule plants from a marshy area and demonstrates separating the layers of the stalk.]

CARRIERE: It’s really satisfying to go out and, oh, cut tulles or cattails or go out and pick sweet grass.

[Back in Ed’s home, Ed prepares nettle fibers for making rope and splits a cedar limb.]

CARRIERE: If I collect it, I got to make something out of it, you know? I can’t just let it sit there, because it’s sitting there saying, hey, use me, use me. Make something out of me.

[ED LAUGHS]

[MUSIC FADES UP]

[The American Museum of Natural History logo appears, followed by the title: Woven Traditions: Northwest Coast Basketry]

[A series of shelves in the Museum’s Anthropology collection are slid open, revealing many woven Northwest Coast baskets of different shapes and patterns.]

AMY TJIONG (Associate Conservator, Division of Anthropology): We have a lot of baskets in our collection.

[More shelves of Northwest Coast woven basketry reflect the diversity of materials and techniques used to create them.]

TJIONG: The plant materials themselves in these baskets, over time, they dry out, they become embrittled, and sometimes when we have to treat objects, it can get complicated.

[The Museum’s Northwest Coast Hall circa 2018 is shown with the caption “Northwest Coast Hall Before Renovation”]

TJIONG: The Northwest Coast Hall is over 100 years old…

[The hall is now shown in the midst of construction with empty cases and scaffolding, with the caption “Northwest Coast Hall During Renovation”]

TJIONG: …and I’m part of the team that is updating, restoring, and conserving the hall.

[Amy Tjiong sits in front of shelves of Northwest Coast basketry in the Museum’s Anthropology collection]

TJIONG: The conservation team has been tasked with conserving 800-plus objects.

[Museum conservators clean and conserve a variety of Northwest Coast collection pieces.]

TJIONG: That involves making sure that the objects are stable for display. It's really important to us to get input and guidance from the community members.

[A conservator uses a special vacuum hose and a brush to remove dust from Northwest Coast baskets.]

TJIONG: We were hoping to find somebody who would be able to tell us more about the materials that we see in these baskets and the technologies. We had reached out to our core advisors and Northwest Coast basketry scholars. Everybody said that we should reach out to Ed.

[Ed Carriere sits at a table laid out with his basketry and basket-making materials and tools in the Museum’s Division of Anthropology. He holds a large woven basket.]

CARRIERE: This clam basket…my specialty. What got me started in weaving.

[Photograph of Ed Carriere with staff members from the Division of Anthropology]

TJIONG: We invited Ed to visit the conservation lab…

[Photograph of Ed holding a cedar tree limb while giving a presentation to Museum staff.]

TJIONG: …for a working visit in 2018.

[Short clips cycle through of Ed holding and describing the variety of baskets and basket-making materials he brought to the Museum.]

TJIONG: He brought, I mean suitcases full of plant materials that he had harvested, and baskets that he had woven.

[Camera pans across four intricately woven Coast Salish baskets with distinct shapes and designs.]

TJIONG: And at the same time, he would have the opportunity to view objects from his area, the Coast Salish region, within the collection.

[Curator Peter Whiteley sits in front of a Northwest Coast house screen with baskets next to him in the Museum’s Division of Anthropology.]

PETER WHITELEY (Curator, Division of Anthropology): We have a great variety of baskets from people all up and down the coast.

[As he names each nation, an example of a basket from that culture appears on screen.]

WHITELEY: Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, from everywhere.

[A map of the Northwest Coast appears onscreen, color-coded to show the territories of the Native nations of that region.]

WHITELEY: But Coast Salish are distinctive.

[The map zooms in on the Coast Salish territory, which remains colorful while the rest of the map fades.]

WHITELEY: The symmetry of the designs, the complexity of the weaves, that's something that Coast Salish is especially known for.

[The camera slowly zooms in on several Coast Salish baskets, showing their intricacy.]

WHITELEY: Basketry, wooden boxes, those were people's containers.

[A Northwest Coast basket rotates in a circle, showing it to us from all angles.

WHITELEY: People in this part of the world didn't make pottery like they do in the native Southwest.

[Examples of Northwest Coast basketry from the Museum’s Anthropology collection.]

WHITELEY: And there are many different types of baskets for different purposes and with a very sophisticated technological knowledge that goes into them.

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: So there’s the clam basket.

[A large rectangular basket with a single handle on the top, with spaces between the warps and wefts.]

CARRIERE: And then the burden basket.

[A more tightly-woven basket with small handles on the sides and a rope around it that would have been used to put across one’s forehead while carrying it.]

CARRIERE: And then there’s the folded bark basket.

[A cylindrical-shaped basket visibly made from a large sheet of bark that has been folded at the bottom.]

CARRIERE: Then there was the hard-coiled cooking basket.

[Several examples of large, very tightly-woven baskets.]

CARRIERE: The weave is so tight that it forms a solid wood vessel, and so it would hold water, and then they could put foods in it and hang hot rocks in there and boil foods quickly in that type of a basket. Which I thought was incredible.

[LAUGHS]

[Photograph of Ed’s Great Grandmother, Julia Jacobs, with several baskets she wove.]

CARRIERE: It was my goal to weave like my ancestors did.

[A series of photographs shows Ed examining baskets and woven pieces in the Museum’s collection, and talking to conservators about basket-weaving materials.]

CARRIERE: So I fulfilled that through archeology and through museums, and seeing these old pieces that are stored away.

TJIONG: But having him bring the harvested materials to the Museum, that's just one piece of a larger story.

[Fade to black.]

[WAVES GENTLY LAPPING]

[Fade up to clear blue water lapping against a rocky beach shore.]

TJIONG: There were many reasons for visiting Ed at his home.

[Leaves gently rustle in a lush forest with thick-trunked trees covered in moss.]

TJIONG: Many of our advisors have told us time and time again how important it was for us to visit the land where they came from.

[Cattails sway in the breeze. Water laps at the beach with dense forested islands in the distance.]

TJIONG: That we will never truly understand until, you know, we've breathed the air, until you know we've seen the landscapes.

[Ed leads Amy through tall grasses and brush.]

TJIONG: He took us he took us along the beach to a sandspit where we were able to harvest these grasses that were taller than us.

[Ed shows Amy some stalks of tule and cattail he just cut.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: They’re a little fragile, but once you get ‘em woven, they’ll make a really pretty little basket.

TJIONG [Voice Over]: Into the forest where you had cherry trees and cedar trees growing.

[Ed shows Amy how he peels outer bark from inner bark on a strip cut from a cedar tree.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: Now, when I make a folded bark basket, I use the whole thing.

TJIONG [Voice Over]: When it comes to the materials, we only see the finished product. Just getting to see these raw materials is helpful so that we're able to identify what we see in the baskets.

[Amy squeezes a freshly cut tule stalk in the sandspit.]

TJIONG [On Camera]: Oh wow, big difference.

[Amy and Ed harvest grasses and tall brush.]

TJIONG: He taught us how to distinguish between, you know, say for example like bear grass and swamp grass. And this isn't something that you would be able to do just by looking at a basket. You would really need to feel the length of the grass.

[Ed demonstrates splitting a cedar limb back at his home.]

TJIONG [Voice Over]: He taught us how to split the cedar limbs into several layers, each one that could be used for weaving.

[Amy splits a cedar limb with Ed’s guidance.]

CARRIERE [On Camera]: If it goes to one side, pull to the other side. Just kind of feel it out.

[Ed uses a knife to cut small twigs off of a long cedar branch.]

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: The difference between a basket maker and a basket weaver is a basket maker buys some of his fibers at the store…

[Ed creates nettle rope by crushing nettle plants, breaking them into thin fibers, and braiding them. He holds out the finished product in his hand.]

CARRIER: …but a basket weaver goes out and collects and splits and makes his own warps and wefts and his own fibers to weave the basket with. So there’s a difference there.

[Ed and Amy walk through the forest and harvest materials. Ed demonstrates various techniques of processing basket-making materials.]

TJIONG: Many of our advisors, including Ed, they have such a deep understanding of these materials and the technologies, more so than then we do as conservators. Just because, unless you've grown up with these materials at your doorstep, you know, these traditions are handed down to you through generations. It would only make sense that they've amassed this deep wealth of knowledge.

[Back at the Museum, Anthropology and Exhibitions staff, including Peter Whiteley, arrange baskets in a mock-up of the display that will be installed in the renovated Northwest Coast hall.]

WHITELEY [Voice Over]: As we think about how to display these baskets, we're really dependent upon the advice of our advisors, and they've offered a great deal of new information that we hadn't even been aware of previously.

[Transition from Peter looking at baskets in Museum mock-up display to Ed and Amy looking at Ed’s baskets in his home.]

WHITELEY: It’s essential to collaborate with First Nations communities, and artists, and scholars, and historians. You have to have those perspectives because that's where the knowledge is, that's where the understanding is.

CARRIERE [On Camera]: A basket tells the story of those people.

[Ed twists and braids fibers into rope.]

CARRIERE [Voice Over]: Even when I’m weaving one of those, I can actually feel my ancestors helping. I can feel them helping my fingers and my hands do the right move to weave with. So I really believe in that theory of through basketry we have a direct link to the past, to our ancestors way back.

[Wide shot of a field with Ed and Amy walking together in the distance.]

[Credits roll.]