Nuu-chah-nulth

Denis Finnin/AMNH Anthropology catalog 16.1/1892 A

Selected features from the Northwest Coast Hall.

The Nuu-chah-nulth are a group of closely related communities on western Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Their U.S. relatives, the Makah, live in northwestern Washington State. The Nuu-chah-nulth traditional way of life is oriented toward the sea and has been shaped by a long tradition of whaling.

[Still portrait of Ḥaa’yuups in regalia.]

ḤAA'YUUPS (Head of the House of Taḳiishtaḳamlthat-ḥ, Huupa‘chesat-ḥ First Nation): My real name is Ḥaa'yuups. I'm a member of the Huupa'chesat-ḥ Tribe. We're from the West Coast of Vancouver Island. We're one of the smallest tribes on the coast. Our territories are located in what is called today the Alberni Valley at the head of Barkley Sound.

Nuu-chah-nulth Language

V. Wells

The Nuu-chah-nulth language is called T'aat'aaqsapa, meaning “putting your words in [proper] order.” Fewer than 50 people speak T'aat'aaqsapa proficiently today. Thla-quas is still learning. She and members of her family were forced to attend a government-run Indian Residential School, where Indigenous languages were forbidden, affecting how much T'aat'aaqsapa was passed on to her. Listen to phrases in the Ehattesaht dialect of T'aat'aaqsapa.

?a?aa | Hello

ʔʔačaqłak | What is your name?

qʷismaḥsas | I would like to do that.

ƛułuk̓um n̓aas | Have a good day.

yaaʔakuks suw̓a | I love you

Speakers: n̓aaskuusaƛ | Fidelia Haiyupis, Earl Smith; Sound recordists: ḥiikʷuusinupsił | Victoria Wells, Justin Wells, AW

Maa’nulthat-ḥ | Our Coastal People

Skilled navigators, the Nuu-chah-nulth are maritime people, attuned to living where water, land, sky, and spirit realms meet.

Every aspect of Nuu-chah-nulth life is linked with the sea, including technologies for fishing, hunting, and travel, names of people and places, oral literature, spiritual practices, dances, and songs.

Click on the 3D model below for a closer look.

During a ceremonial feast, a dancer wearing the Mamachaḳtl hinkiitsim (shark rider headdress) above might tip and sway as if swimming underwater and pull a hidden cord to bring the human figure to life. The figure is riding an enormous basking shark.

Tl’eḥapiiḥ hinkiitsim | Fish headdress The fish shown on this headdress is a kind of rockfish called tl’eḥapiiḥ, or “big red,” commonly known as the Red Snapper fish. It provides variety in a diet centered on salmon, shellfish and, historically, whale meat. Fish are displayed on many Nuu-chah-nulth ceremonial treasures, reflecting people’s high respect for these beings.

Tl’eḥapiiḥ hinkiitsim | Fish headdress The fish shown on this headdress is a kind of rockfish called tl’eḥapiiḥ, or “big red,” commonly known as the Red Snapper fish. It provides variety in a diet centered on salmon, shellfish and, historically, whale meat. Fish are displayed on many Nuu-chah-nulth ceremonial treasures, reflecting people’s high respect for these beings. AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1944

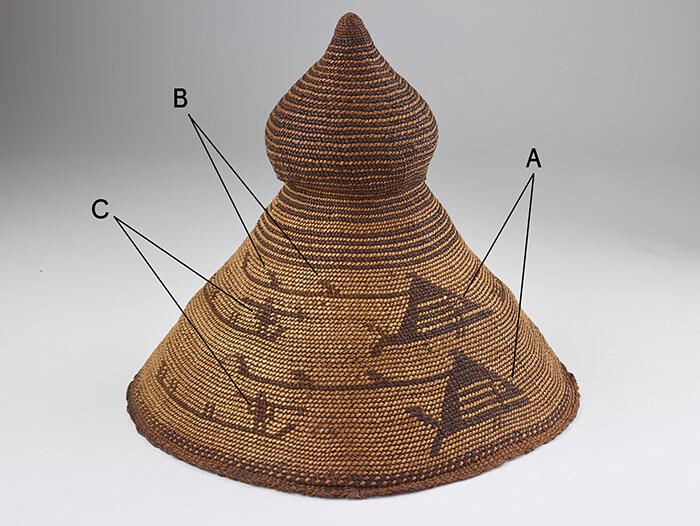

Uu-uut’aḥpuks | Whale Hunter's hat Scenes from a humpback whale hunt decorate this hat, made in the late 1700s or early 1800s. Its design marked the status of a Nuu-chah-nulth Whaling Chief. Two harpooned whales (A) flee, trailing ropes. The short lines jutting up from the ropes represent sealskin floats (B), which slow the whales’ progress. A Chief (C) stands in the bow of each canoe, holding aloft his whaling harpoon, leading the hunt to provide for his people.

Uu-uut’aḥpuks | Whale Hunter's hat Scenes from a humpback whale hunt decorate this hat, made in the late 1700s or early 1800s. Its design marked the status of a Nuu-chah-nulth Whaling Chief. Two harpooned whales (A) flee, trailing ropes. The short lines jutting up from the ropes represent sealskin floats (B), which slow the whales’ progress. A Chief (C) stands in the bow of each canoe, holding aloft his whaling harpoon, leading the hunt to provide for his people.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/7959

Landmark Case

In the 1880s, the Canadian government set aside small pockets of land within Nuu-chah-nulth territories for people to live and gather traditional foods. Since then, Nuu-chah-nulth people have continuously fought for broader recognition of their fishing, hunting, land, and sea rights.

After a long legal battle, in 2009 the Supreme Court of Canada recognized the Nuu-chah-nulth aboriginal right to fish in territorial waters, and to sell their catch commercially. Canada appealed the decision, but the court upheld it.

E. Plummer/Ha-Shilth-Sa First Nations Newspaper

Uu-uut’aḥ | Whale Hunting

Becoming a Whaler

For more than 4,000 years, Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs provided for their people by hunting whales, which migrate along their shores in spring and fall. Whaling was a privilege, passed down in chiefly families. Each whaler followed a strict code, inheriting a specific position in the canoe and a well-defined set of tasks. Whalers were initiated into their roles and trained physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually throughout life. They prayed with great discipline, often turning to their whaling Ancestors for spiritual aid.

When a Whaler went out to sea, he didn’t harpoon the first whale he saw, he identified the one that he was intended to kill. That one was looking for him, too. They recognized each other. The whale gives himself to the hunter who has been praying and who is clean [i.e. spiritually prepared].

—Willie Sport

Huu-ay-aht First Nations, Nuumaḳimyiis, British Columbia

Iiḥtuup | Whale Carving

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1082

Marine Architecture

With its streamlined form, a Nuu-chah-nulth canoe is ingeniously designed to withstand the wind and waves of the Pacific Ocean.

Yashmaḳats | Sealing canoe with figures A sealer crouches at the bow of this miniature canoe, an outstanding representation of a West Coast vessel. The lip running along the outside edge of the canoe repelled water on rough, open seas. The harpooner lifts his weapon, ready to spear a sleeping seal. The standing figure represents Tl’eḥasim, a great Chief of the Uu-inmitisat-ḥ people.

Yashmaḳats | Sealing canoe with figures A sealer crouches at the bow of this miniature canoe, an outstanding representation of a West Coast vessel. The lip running along the outside edge of the canoe repelled water on rough, open seas. The harpooner lifts his weapon, ready to spear a sleeping seal. The standing figure represents Tl’eḥasim, a great Chief of the Uu-inmitisat-ḥ people.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1689

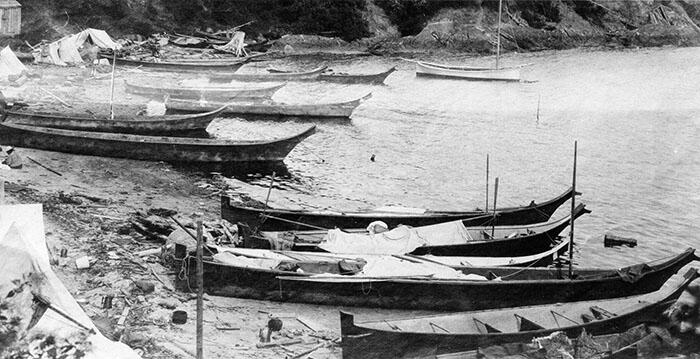

Nuu-chah-nulth canoes, c. 1910.

Nuu-chah-nulth canoes, c. 1910.The Bill Reid Centre at Simon Fraser University

Chief Maquinna’s Ceremonial Curtain

Ha-Shilth-Sa Newspaper

There is a name for conservation in the Nuu-chah-nulth language: uḥmuuwashit—‘keep some and not take all.’ This word pertains to careful use of the fishery. People knew how much they could use, and they didn’t ever use it all.

—Earl Maquinna George

Taayii Ḥa’wilth, Ahousaht First Nation, Maaḳtosiis, British Columbia

In the video below, hear from the son of Chief Earl Maquinna George, Chief Maquinna | Lewis George, who inherited his father’s thliitsapilthim, or ceremonial curtain. This curtain tells the history of 17 generations of their family.

UKTHAASISH MAQUINNA: If you take a look at a curtain it's a story. It's a history that belongs to to my family and it belongs to the Aaḥuusat-ḥ People.

[Illustration of fish on big house]

MAQUINNA: Ukthaasish Maquinna. Hishtaḳshitl Aaḥuusat-ḥ.

[Maquinna speaks to camera]

MAQUINNA: My name is Maquinna and I come from Aaḥuusat-ḥ.

[Archival photo of people holding up a large piece of fabric, which bears figures of people and animals.]

MAQUINNA: My late father Earl Maquinna, he was needing a curtain to be done and my older brother Corbett spoke with John Jacobson to iron out what should go on that curtain, what needs to go on that curtain. And they knew what needed to go on it, but they needed an artist to do the rendering of it, to put it on the curtain.

[Another archival photo of the same curtain, this time in progress, with fewer figures completed.]

MAQUINNA: Ron did this curtain for my dad, my late dad, 20-some odd years, I guess, 25 years back or when it was originally made. And it was passed to me. It wasn't a very large curtain. We added to it.

[An archival photo of people standing in front of the curtain, now longer and even more filled in with figures.]

MAQUINNA: The curtain was 20 feet and we added 20 feet on each side. So, I got in touch with my good friend Ron and I said, "Ron, we need to start working on this curtain. I want to make it bigger. I want to add things that I think that need to be added to it."

[Maquinna speaks to camera.]

MAQUINNA: And he he came over and spent, I don't know, two to three weeks I think we worked on it straight, we didn't stop.

[Artist Ḥaa’yuups (Ron Hamilton) holds one edge of the curtain in an archival photo.]

MAQUINNA: We sat down [with] my brother Corby. We really, really talked about what needed to go on a curtain.

[Close-ups of faces, figures, animals, and boats on the curtain.]

MAQUINNA: Some of the Elders that I had spoken to earlier, talking about things that should go on there to make sure that we're informing everybody that this what's on our curtain is our history, is our link to way back 17 generations of my family and what it looked after in Aaḥuusat-ḥ.

[Maquinna speaks to camera.]

MAQUINNA: And there's still lots to go on it. I'm going to leave that for my son to do, to finish.

Hinkiitsim

Nuu-chah-nulth people call this type of headdress a hinkiitsim. It is worn above a dancer’s forehead and appears in pairs—male and female. The one below (AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1900) represents a serpent—possibly Ḥayitl’iik, a lightning serpent, an important supernatural being in the Nuu-chah-nulth tradition. This headdress is from Tla-o-qui-aht territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1900

The right to wear a hinkiitsim in potlatches, or ceremonial feasts, is handed down from generation to generation.

S. Morrow/Ha-Shilth-Sa First Nations Newspaper

Below, several dancers wear hinkiitsim in a late 1920s Dominion Day Parade, the precursor to Canada Day. On the far right of the image, Ha’wilth (Chief) Kwitchiinin carries a placard saying ”We are the Real Native Sons of Canada.” The placard was a political protest against the formation of a non-Indigenous group calling themselves the “Native Sons of Canada.”

Alberni Valley Museum Photograph Collection PN01873

Mamuu | Weaving

From plants that grow in forests, marshes, and tidal areas, Nuu-chah-nulth weavers fashion a wide variety of textiles. In the 1800s and earlier, clothing woven of finely shredded cedar bark was everyday wear. Today, weavers continue to gather cedar bark from living trees and twine the fibers into ceremonial garments and sturdy baskets.

Textile Tools

Weavers pound cedar bark to separate the layers, then shred it into soft fibers. Two of the cedar processing tools below are made of whalebone, showing the importance of whaling to Nuu-chah-nulth people.

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/2096

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/712

AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1840

Cedar Fabric

Tl’itinkw | Cape A woman wearing this cape would be well protected from rain, snow, and sun. It was woven of water-resistant cedar bark—heavily processed and pounded until supple—and rubbed with ratfish oil. The trim at the neckline of capes such as this was traditionally made from k’wak’watl (sea otter fur).

Tl’itinkw | Cape A woman wearing this cape would be well protected from rain, snow, and sun. It was woven of water-resistant cedar bark—heavily processed and pounded until supple—and rubbed with ratfish oil. The trim at the neckline of capes such as this was traditionally made from k’wak’watl (sea otter fur).AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/1875

Thleḥop’em | Vest This is an example of less processed cedar fabric. It is worn with the two front panels folded over the chest and belted with a cord.

Thleḥop’em | Vest This is an example of less processed cedar fabric. It is worn with the two front panels folded over the chest and belted with a cord.AMNH Anthropology catalog 16/9763

Emtii | Nuu-chah-nulth Names

The Northwest Coast Hall’s Co-Curator Ḥaa’yuups explains the significance of names for the Nuu-chah-nulth community.

[Northwest Coast Hall Co-Curator Ḥaa’yuups speaks in the Museum’s collections space.]

ḤAA'YUUPS: Names have meant a lot—they mean a lot—in my community. But recognizing they mean a lot and knowing their importance and learning more and more, various facets of information about those things, about names in a general sense and about particular names, I became very interested in names. And of course, having been given so many names, it seems incumbent upon me to do something with that.

Meet some people from the Nuu-chah-nulth community, learn their names, and discover their names’ meaning and significance.

Ḥaa’yuups

Ḥaa’yuups

Ḥaa’yuups

Ḥaa’yuups

Ḥaa’yuups

More Resources

Nuu-chah-nulth Co-Curator

Ḥaa’yuups, Head of the House of

Taḳiishtaḳamlthat-ḥ, Huupa‘chesat-ḥ First Nation