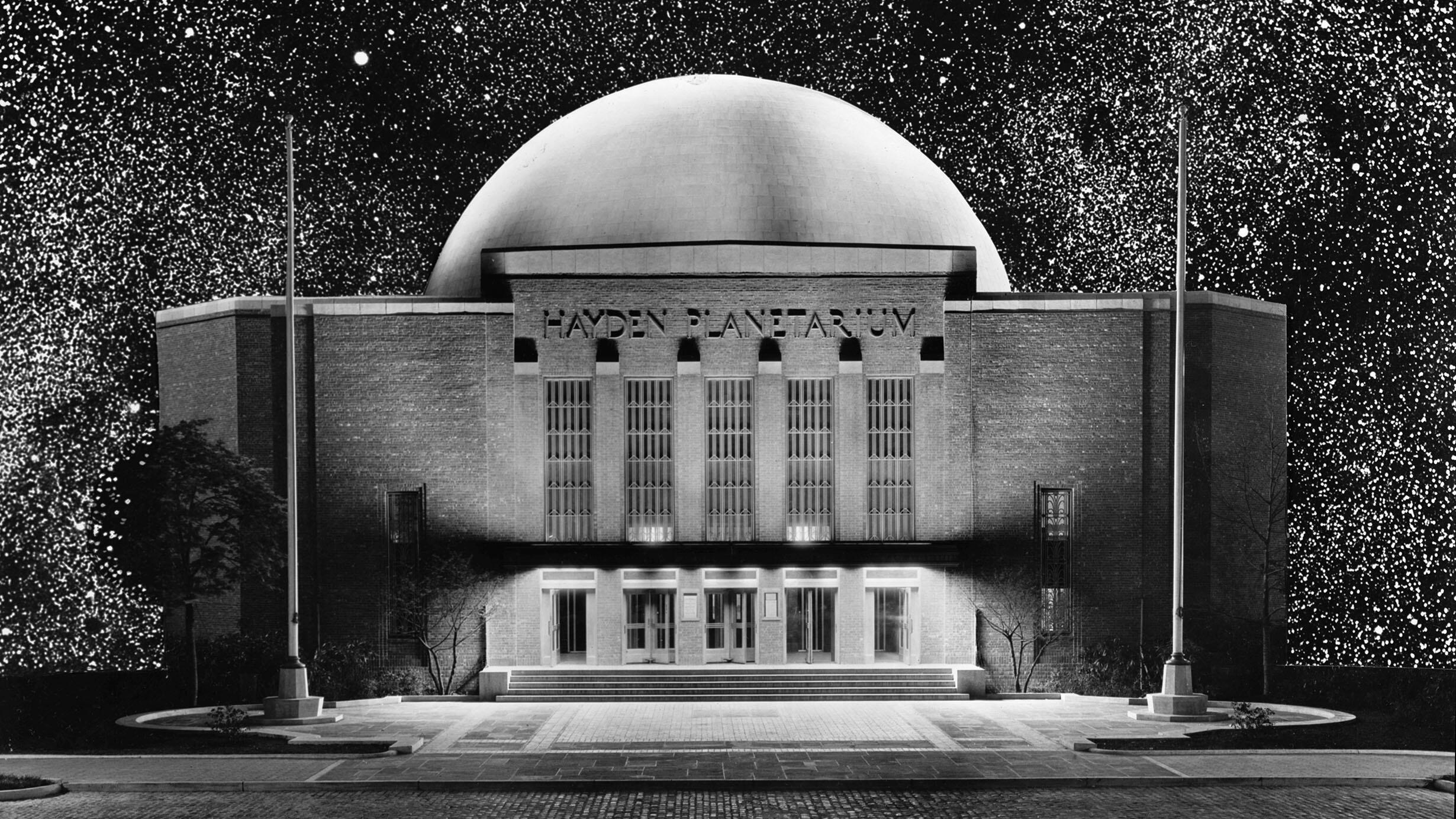

When the Hayden Planetarium opened on October 3, 1935, lines stretched down the block, and in its first year the planetarium drew more than half a million visitors.

When the Hayden Planetarium opened on October 3, 1935, lines stretched down the block, and in its first year the planetarium drew more than half a million visitors.© AMNH Library/Image no. 316044

Charles Hayden was born in 1870, the same year a total solar eclipse brought a team of scientists together to observe the totality over Sicily with the relatively new technology of spectroscopy, which split light into wavelengths that could be analyzed for various properties. The expedition was a milestone in the nascent field of “physical astronomy”—or astrophysics, as we know it today. And the next few decades were an exciting age of discovery.

Researchers uncovered unknown aspects of the universe: the chemical makeup of stars, radio waves from space, that the Sun is mostly hydrogen, and that the Milky Way is just one of many galaxies. And Charles Hayden, whose life coincided with the opening of these new cosmic frontiers, would play a crucial role in bringing them to generations of New Yorkers and to visitors from around the world.

© AMNH Library/Image no. 282187

Although the Museum began planning “an astronomic section” in 1925, Chicago’s Adler Planetarium opened first, becoming the Western Hemisphere’s only planetarium in May 1930. Crowds flocked, and when Chicago opened the Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933, attendance topped 1.2 million within a year. One of the starry-eyed planetarium visitors was Charles Hayden.

“Charles Hayden was deeply inspired by our universe and wanted to bring that sense of awe to others, especially to the next generation.”

The experience so thrilled him that, within just a few months and in the middle of the Great Depression, he pledged funds to help build a planetarium in New York City. “I believe the planetarium is not only an interesting and instructive thing but that it should give more lively and sincere appreciation of the magnitude of the universe,” Hayden told The New York Times and other newspapers.

His gift went towards the creation of a Copernican exhibit on the first floor, which displayed the six planets nearest to the Sun revolving at their proper relative speeds, and a state-of-the-art Zeiss projector for the new building’s hemispherical dome. Hayden turned the first shovelful of earth at the groundbreaking for what would become his namesake planetarium in May 1934.

© AMNH Library/Image no 31922

His hopes came true. When the planetarium opened to the public on October 3, 1935, lines stretched down the block. In its first year, the Hayden Planetarium drew more than half a million visitors, plus more than 130,000 New York City schoolchildren who were admitted without charge, to see the stars in the night sky or to listen to illustrated lectures.

© AMNH Library/Image no. 288037

The 734-seat circular projection chamber featured a white dome of perforated stainless steel, which served as the screen on which images of the heavenly bodies were cast by the Zeiss projector, supplemented by lantern slides. Averaging nine shows a year, the Hayden Planetarium would cover such subjects as “4,000 Years of Astronomy,” “The Expanding Universe,” and the prescient “Rocket to the Moon.” In 1951, the Hayden Planetarium hosted the First Annual Symposium on Space Travel.

Although Charles Hayden died in 1937, his legacy of support for the educational mission of the Museum has continued through his foundation. Among other things, the Charles Hayden Foundation has contributed to periodic upgrades of the Zeiss projector, and, in 1999, provided a grant for the new Hayden Planetarium within the Rose Center for Earth and Space.

D. Finnin/©AMNH

“Charles Hayden was deeply inspired by our universe and wanted to bring that sense of awe to others, especially to the next generation,” says Kenneth D. Merin, president and CEO of the Charles Hayden Foundation. “The Hayden Planetarium continues to be the ultimate place for visitors of all ages, and especially for New York City students, to be transported and to discover the vastness and beauty of the cosmos for themselves.”

When the Museum’s new Space Show, Worlds Beyond Earth, which was developed with the support of the Hayden Foundation, opens on January 21, it will kick off a year of Hayden Planetarium programs to celebrate the man behind New York’s beloved planetarium.

It will be a fitting tribute to the person who was committed to sharing the magnitude of the universe with others, and a reminder of the mysteries, wonders, and discoveries that still await.

A version of this story appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of the Member magazine, Rotunda.