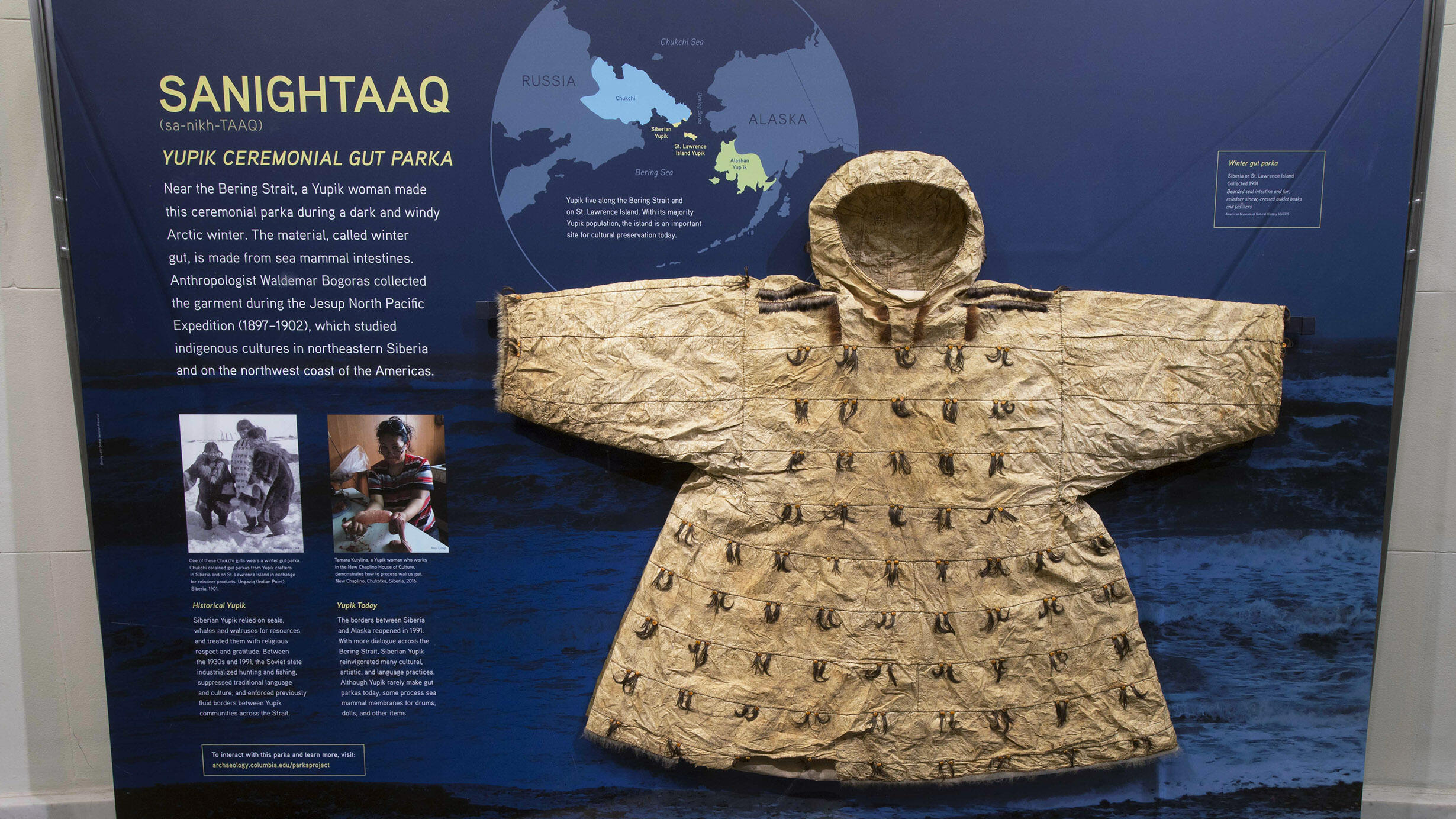

The parka on display in the Grand Gallery exhibit Sanightaaq: Yupik Ceremonial Gut Parka is one of 100 coats that underwent restoration by the Museum's Objects Conservation Laboratory.

The parka on display in the Grand Gallery exhibit Sanightaaq: Yupik Ceremonial Gut Parka is one of 100 coats that underwent restoration by the Museum's Objects Conservation Laboratory. C. Chesek/© AMNH

In “The Guts and Glory of Object Conservation,” an episode of the Museum’s video series about collections, conservators and anthropologists discuss preserving century-old cultural materials from the historic Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897–1902), which undertook a groundbreaking study of indigenous cultures on both sides of the Bering Strait. Now, in the Grand Gallery, you can see a striking example of that work—a recently restored coat collected from the Yupik people in 1901.

The coat is a ceremonial gut parka made primarily from the processed intestine of a bearded seal and represents the cultural heritage of a people whose traditions were nearly erased during decades under the Soviet regime.

The Yupik live along the Bering Strait in Siberia and Alaska and are the majority population on St. Lawrence Island. Historically, Siberian Yupik relied on seals, whales, and walruses for resources.

Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution GA 30-87

Bearded seal intestines can be 65 feet long, and to process them into a wearable material a Yupik woman unravels and inflates the intestines outdoors, then cleans, scrapes, and cuts them. The season in which the guts are processed determine how the parka is used: drying them out in cold winter wind produces “winter gut,” considered sacred for ceremonial use, while drying them during warmer months produces a practical, waterproof material known as “summer gut.”

Click or tap into the window below and use the hand tool to manipulate a three-dimensional model of the restored gut parka.

The parka on display was made during a dark, windy Arctic winter and finished with seal fur, reindeer sinew, and crested auklet beaks and feathers. Although Yupik rarely make gut parkas today, some process sea mammal membranes for drums, dolls, and other items.

This parka is one of 100 coats that underwent intensive restoration by the Museum’s Objects Conservation Laboratory as part of the Museum’s Siberian Conservation Project to document, research, and treat the Jesup collections. Native consultation was vital to that work, and Siberian scholars and artisans shared their knowledge and memories to help conservators understand gut parka processing and care.

“The challenge of this project for the student-curators was to distill multiple worlds,” says Laurel Kendall, curator of Asian ethnology at the Museum. “Yupik life at the time the parka was made, Yupik heritage today, and the work of the Museum's conservation lab in consultation with Yupik artisans.”

The Museum’s Jesup collections became especially valued as a cultural repository when the Soviet Union inhibited contact between Yupik communities across the Strait and suppressed traditional language and culture from the 1930s to 1991. Since the borders between Siberia and Alaska reopened in 1991, Siberian Yupik have reinvigorated many cultural, artistic, and language practices, and the Museum remains committed to making the historic Jesup collection accessible to descendant communities in Siberia.

In the episode of the Museum’s video series Shelf Life about object conservation and the Siberian Conservation Project, Vera Solovyeva, a Siberian scholar from the Sakha Republic, who worked with Museum conservators, said the collection—with its range of material, spiritual objects, and photographs of her ancestors in everyday life—showed her “what was truly the ancestral way of living.”

Shelf Life #15 - The Guts and Glory of Object Conservation - Visual Cue Transcript

[WIND BLOWS, DOGS PANT AND BARK]

An animated sequence combining black and white archival photographs—sled dogs race through the snow.

LAUREL KENDALL: When you go to the northeast of Siberia, that part of the world, it's very stark. But in its starkness, it's beautiful.

A gust of wind blows aside snow to reveal people riding on reindeer. Mountains rise on the far horizon.

KENDALL: The far north is tundra, and forest, and a long, empty coast.

Animated sequence continues as mountains give way to taiga forest and then to a coastline.

[WAVES CRASH]

[MUSIC PLAYS]

Camera zooms out on a hand-drawn map to reveal Siberia, Alaska, and the lands surrounding the North Pacific Ocean.

KENDALL: The Jesup North Pacific Expedition was probably the most ambitious anthropology expedition of all time.

Archival images of anthropologists are superimposed on the map of the Northwestern coast of North America.

KENDALL: The idea was to take two teams of experts—one on the American side,

Camera pans left to images of anthropologists on the Siberian side of the Bering Strait.

KENDALL: one on the Siberian side of the Bering Strait,

Dotted lines animate from one side of the Bering Strait to the other. A question mark appears between the coasts.

KENDALL: and have them explore the question of who came over the Strait, when.

Curator Laurel Kendall stands, looking at camera.

KENDALL: I'm Laurel Kendall. I curate the Asian Ethnographic Collection at the American Museum of Natural History.

[MUSIC PLAYS]

Shelf Life title sequence. Specimens and artifacts from the Museum's collections fade in and out.

Objects from the Siberian collection appear in quick succession.

KENDALL: The scope of the Jesup collections is enormous. Their brief was to collect every aspect of how people live.

Curator Laurel Kendall interviewed at desk.

KENDALL: Well, that's impossible. But they came as close as they possibly could.

Compactor opens to reveal shelves of objects from the Siberian collection.

JUDITH LEVINSON: The Siberian collection numbered more than 5,000 pieces.

Three conservators work at long tables in the Museum's Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: We chose a hundred of those to focus on for full conservation treatment.

Judith Levinson looks holds top of birch bark box and looks up at camera.

LEVINSON: My name is Judith Levinson. I'm Director of Conservation in the Division of Anthropology.

Levinson sits at table in Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: We're able to have very well developed consultation and collaboration with Native groups

Montage of consultations between conservators and Native peoples.

Levinson interviewed at table in Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: and part of why we were able to do this was that we have a very important project participant,

Still images of Vera Solovyeva talking with conservators, and with colleagues in Siberia.

LEVINSON: who is a scholar, who is a native Siberian.

Vera Solovyeva stands in Anthropology collections, looks at camera.

VERA SOLOVYEVA: My name is Vera Alexseyevna Solovyeva, and I am a PhD candidate at George Mason University.

[MUSIC PLAYS]

Hands pull out drawers in the collection, showing different objects on the shelves.

Solovyeva interviewed in collection space.

SOLOVYEVA: This collection is very important because it has probably the most elaborate collection in the whole world about our people's pre-Soviet period.

Archival photos showing different Siberian individuals.

Montage of objects from the Siberian collection.

SOLOVYEVA: And it has, like, the full range of the material and spiritual culture.

Archival photos of everyday life in early 20th century Siberia.

SOLOVYEVA: And then, second, it has pictures of our ancestors' everyday life.

Black and white animation of boy on sled, being pulled by reindeer. Text reads "Soviet Film, 1928."

SOLOVYEVA: When the Soviets came to the power, they tried to erase the memory of people.

Animation continues. A Siberian boy sits at a desk, dreaming of being pulled on sled. Dream fades away and picture of Lenin appears.

SOLOVYEVA: So, you know, they destroyed all items that belong to the shamans, the rituals.

Animation continues. Siberians in fur coats walk away from tents in the snow, leaving an empty landscape.

Solovyeva interviewed in collection space.

SOLOVYEVA: When the Soviet Union collapsed,

Montage of 1990s photos depicting Siberians engaging in traditional crafts and practices.

SOLOVYEVA: Indigenous People started to have interest to revitalizing their culture and their spirituality.

Solovyeva interviewed in collection space.

SOLOVYEVA: In my view, the Museum's collection have a very important role to showing what was truly ancestral way of living.

Archival image of female shaman drumming.

In the present day, conservator Amy Tjiong turns over a shaman's drum in the Anthropology collection.

LEVINSON: Each of these pieces holds valuable information to people from around the world,

Levinson interviewed at table in the Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: and we want to preserve them for many years to come.

A conservator cleans a birch bark map with a small brush.

LEVINSON: Here in the Objects Conservation Lab, we work to stabilize the physical condition of the objects.

Levinson interviewed at table in the Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: What I love about conservation is it's a fabulous blend of science, art, and history, and cultural studies.

Conservator Amy Tjiong works on the edge of a colorful Siberian robe made from fish skin.

AMY TJIONG: I get to work on a variety of material, including robes that were made from fish skin,

Hands turn over an elaborately decorated birch bark container.

TJIONG: containers that were made from birch bark,

Tjiong and a collections staff member carefully place a fur coat on a table.

TJIONG: coats that were made from reindeer hide.

Tjiong, standing in a row of the Anthropology collection, holds a birch bark container.

TJIONG: My name is Amy Tjiong. I'm a conservator within the Objects Conservation Lab at the American Museum of Natural History.

A conservator wearing blue latex gloves enters information onto an iPad.

Close up of the iPad, showing a diagram of a gut skin coat.

TJIONG: The first thing that we'll do is documentation of the object before treatment.

Close up of a camera snapping a picture. A white flash.

LEVINSON: We'll take pictures.

Photos of different angles of a Siberian fur coat appear in quick succession, punctuated by camera flashes.

A photo of a fish skin robe is overlaid with animation showing areas where conservation treatment will be necessary. Labels reading, "Major crease," "Loss from insect damage," "Staining," and "Failed stitches" appear with corresponding indications on the robe.

LEVINSON: We will write a condition report, documenting everything that we see.

Levinson interviewed at table in Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: And we're able to take teeny-weeny samples,

Tjiong consults with a forensic anthropologist. They hold up slides with small tissue samples and indicate microscopic images on a computer screen.

LEVINSON: and have particular kinds of scientific analysis done that help us identify the materials of manufacture

Levinson interviewed at table in Objects Conservation Laboratory.

LEVINSON: in ways that couldn't be done by the anthropologists who formed the collection.

Black and white archival portraits of anthropologists.

Mammalogist holding a wolverine specimen consults with Tjiong in the Mammalogy Department.

LEVINSON: So, for instance, because we work in a natural history museum,

In animated sequence, the camera zooms into a Siberian fur coat, to reveal a microscopic image of a single hair.

LEVINSON: we could pull individual hairs from a fur

Comparison microscope images of mammal hairs—labeled beaver, seal, reindeer, etc.—pop up around the sample hair.

LEVINSON: and compare it to our vouchered specimens in the Mammalogy collection

All hair images disappear, except reindeer. Image flips to reveal an illustration of a reindeer. Image grows in size, flips to reveal a photo of a reindeer superimposed on a map of Siberia.

LEVINSON: to identify the exact animals that came from Siberia.

A conservator holds a paint palette and leans over to dab a gut skin coat with a small brush.

LEVINSON: Once we've gathered all this information, we develop the treatment plan, and actually start treating.

Montage of conservation treatments – paper laid over a birch bark map, a metal tool is gently rubbed onto a coat, a brush mixes paint on a palette, scissors cut a piece of material.

LEVINSON: We may work to replace missing parts or correct surface finishes. But we use materials that are easily reversible.

Wide shot of conservators working on various pieces from the Siberian collection.

TJIONG: Among the objects that were chosen for treatment are 14 gut skin parkas.

Close up on seam of gut skin parka.

Tjiong interviewed in Anthropology collection space.

TJIONG: They're constructed from bands of intestine

Series of still images showing various gut skin parkas from the Siberian collection.

TJIONG: that have been cut open and flattened.

Hands in latex gloves wash intestines in industrial sink.

TJIONG: To better understand this material, I attended a gut skin processing workshop up in Seattle.

Still image of a large, long, inflated intestine laid out on a blue tarp.

Tjiong interviewed in Anthropology collection space.

TJIONG: You know, with gut lovers. I mean, there was- People who have a real fondness for studying gut skin.

Woman inflates intestine by blowing into it. Another woman and a man stretch out inflated intestine.

TJIONG: I was able to learn from a Native artist from Kodiak, and also a curator at the Burke Museum who is Aleutic.

Tjiong interviewed in Anthropology collection space.

TJIONG: And both of them have experience processing intestines.

[PEOPLE SHOUTING, OARS SPLASHING]

Several boats full of rowers move through water. Mountains tower in background.

TJIONG: And then, we went to Siberia

Montage of Solovyeva and Tjiong speaking with members of the Siberian community.

TJIONG: to reach out to members of the community, to try to see if there was any remaining knowledge.

Tjiong interviewed in Anthropology collection space.

TJIONG: And one of the most important goals for us was to share information about the collection

Still images of Tjiong and Solovyeva making presentations to Siberian audience.

TJIONG: to the members of the community there.

Still images of Solovyeva and Siberian people examining objects from the Jesup North Pacific collection.

SOLOVYEVA: The Museum's collection—it's really important to value again our culture.

Solovyeva interviewed in Anthropology collection space.

SOLOVYEVA: Actually, when I came I just- I- I want first, when I saw that, I almost cry. Yeah. Because, you know, like, it's- I never saw this kind of clothing before, for example. I didn't even realize that they exist. And to see them, it was, like, oh wow.

Tjiong works on elaborately decorated fish skin robe.

TJIONG: I do love what I do. I find it meaningful to preserve these cultural artifacts. They all come with such an amazing history I would love to see that they're here for as long as possible.

“It’s really important to value again our culture, “Solovyeva said. “I never saw this kind of clothing, for example. I didn’t realize they exist[ed].”

The new exhibit, titled Sanightaaq: Yupik Ceremonial Gut Parka, was produced by a team of Museum staff and students in the Museum Anthropology Master of Arts Program offered jointly by Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History.

Sanightaaq: Yupik Ceremonial Gut Parka is on view in the Grand Gallery through September 2, 2019.