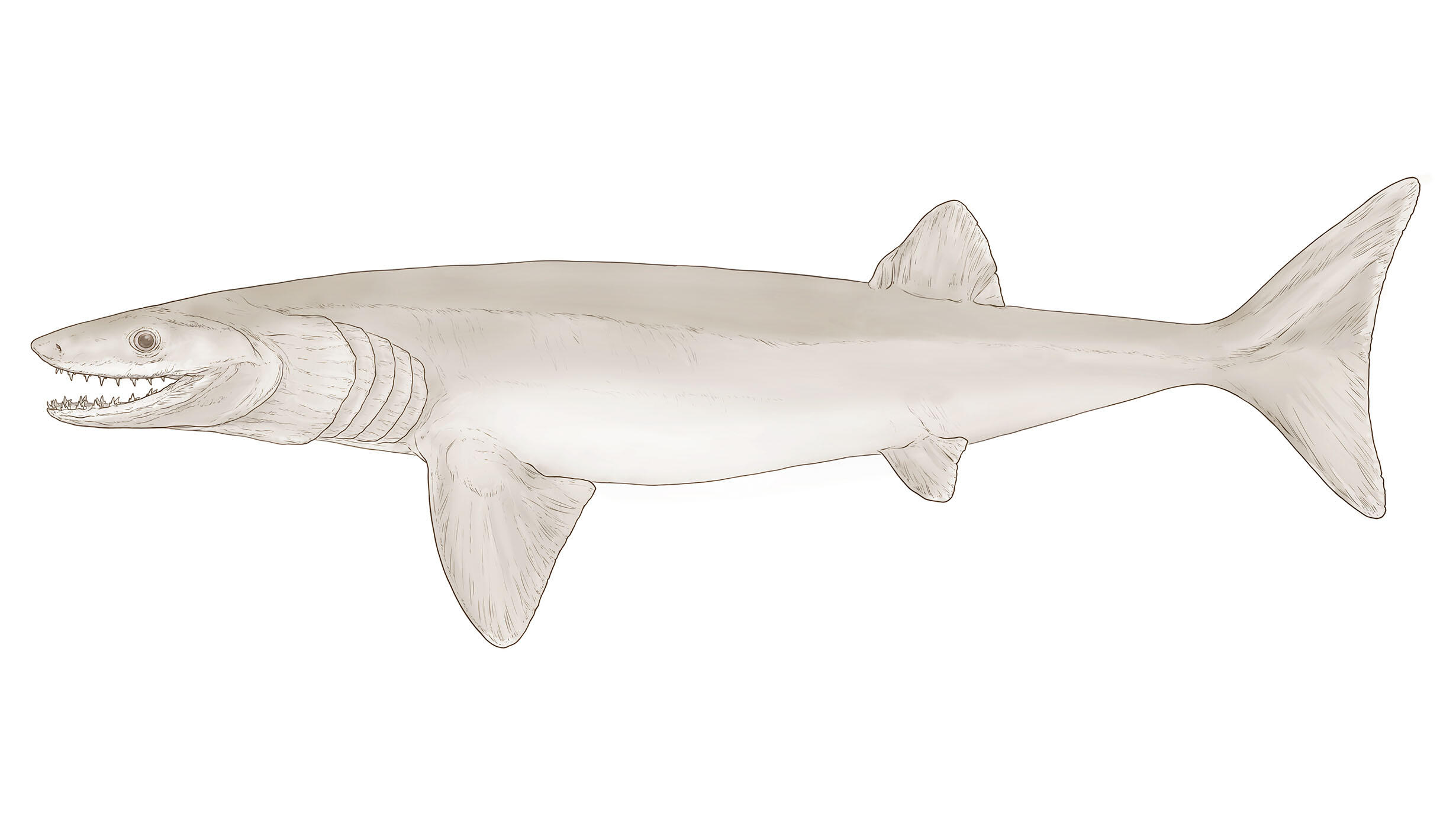

An artist’s reconstruction of the new shark-like species Cosmoselachus mehlingi.

An artist’s reconstruction of the new shark-like species Cosmoselachus mehlingi. © AMNH

Researchers have described a new ancient shark-like species that was collected in Arkansas 45 years ago and fills an important role in understanding an enigmatic and bizarre group of fishes.

The new species, Cosmoselachus mehlingi, lived 326 million years ago and is named after Senior Museum Specialist Carl Mehling, who has worked in the Museum’s Paleontology Division collections for 34 years, the first five years as a volunteer.

“Carl is a cornerstone of the vertebrate paleontology community,” said Allison Bronson, the lead author of the new study in the journal Geodiversitas that describes Cosmoselachus, and a graduate of the Museum’s Richard Gilder Graduate School. “He’s supported dozens of Museum paleontology students over the years. But he’s also a person with a deep appreciation for the strangest and most enigmatic products of evolution. We’re delighted to honor him with a weird old dead fish!”

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

Bronson, now a researcher at Cal Poly Humboldt, along with colleagues from the Museum, the University of Florida, and Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle in France, focused on a fossil specimen collected in the 1970s by Royal and Gene Mapes, a husband-and-wife team of scientists and professors at Ohio University whose collection was donated to the Museum in 2013.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

NEIL LANDMAN (Curator, Division of Paleontology): This was a tremendous collection of around 550,000 specimens of marine invertebrates and vertebrates.

Royal Mapes and his wife Gene Mapes, they were professors at Ohio University. And over the last 45 years, they've been collecting fossils.

Most of the fossils they collect are marine fossils in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas. We don't have a good representation of that in our collections already.

Ammonoids belong to the group cephalopods, part of the mollusks. And the cephalopods are distinguished from the clams and the snails in that cephalopods learned how to swim in the water. So when you think of cephalopods, there's octopus, there's squids, there's the pearly nautilus. And the ammonoids are a big part of it. But that group of cephalopods is now extinct. What we see is their beautiful outer shell. But there is a complex internal anatomy, including the jaws.

And in the Mapes collection, there are many specimens that have preserved their jaws inside the shells. It's a very rare occurrence. It takes very unusual circumstances. But it's just perfect for our research. And it lets me understand the behavior and anatomy of ammonoids a lot better.

JOHN MAISEY (Curator, Division of Paleontology): Royal and his wife have an innate ability to collect and find, and collect fossil sharks and other fossil fish in remarkably good preservation in places where nobody else has been able to find them.

These are almost three dimensional. They're not flat and crushed and broken. They're beautifully-preserved fossils that we can then scan, and in the computer, we can extract the skeletal structures in a great deal of detail.

This is a complete head of a little tiny shark. Inside this rock, there's every little piece of all these gill arches, and all the rest of the skeleton. The jaws and other things. Everything's preserved in exquisite detail, but you can only see it by scanning it and processing the scan using computer technology. And that's what we've been doing.

This is one of these fossils from Arkansas, which I think should be renamed Sharkansas, that is so spectacular. Even though it doesn't look like, in scientific terms, it's really significant. It's a major discovery.

It's not just getting a whole bunch of new fossils, but it's what they are, and what they represent that's really important to us.

LANDMAN: You always look to future generations.

I see the value of this collection, and the treasures in this collection, that graduate students in the future, curators in the future, are going to be able to mine this collection for generations to come.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Following the donation, the Cosmoselachus fossil was CT-scanned at the Museum and the team worked for many months to reconstruct its anatomy, including dozens of tiny pieces of cartilage.

Once the reconstruction was complete, the researchers placed the specimen in the tree of life of early cartilaginous fishes, finding that it plays an important role in understanding the evolution of an enigmatic group called the symmoriiforms.

Cosmoselachus mehlingi, photographed in the late 1970s, positioned to show the underside of the throat, jaws, and pectoral fins.

Cosmoselachus mehlingi, photographed in the late 1970s, positioned to show the underside of the throat, jaws, and pectoral fins.© Royal Mapes

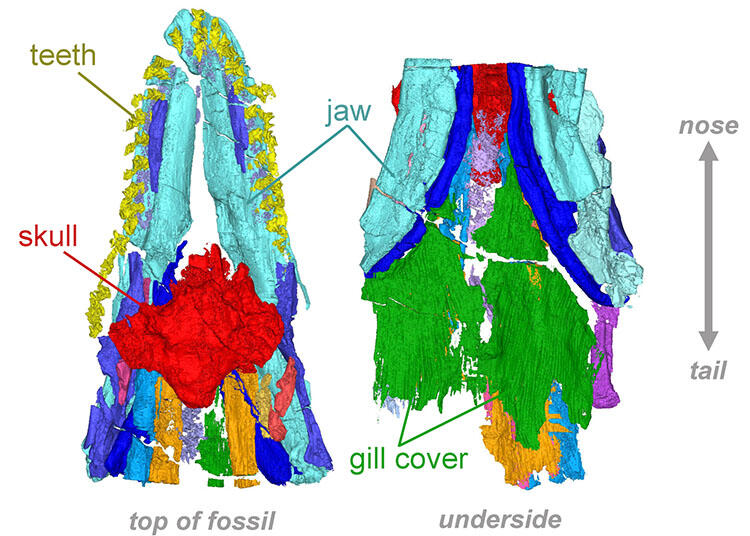

Rendering of the top of the fossil’s skull and jaws alongside a rendering of the fossil’s throat (viewed from below), made from CT scanning. The gill cover (green) is unlike the anatomy of any other species of shark.

Rendering of the top of the fossil’s skull and jaws alongside a rendering of the fossil’s throat (viewed from below), made from CT scanning. The gill cover (green) is unlike the anatomy of any other species of shark.© Allison Bronson

This group has alternately been linked with sharks and ratfish, with different researchers coming to different conclusions. Cosmoselachus has mostly sharklike features, but with long pieces of cartilage that form a gill cover, which is only seen in ratfish today.

The genus name—Cosmoselachus—was given for Mehling’s nickname “Cosm,” in recognition of his “contributions toward the acquisition and identification of numerous fossil chondrichthyans, as well as his indefatigable enthusiasm for all unusual vertebrates and many years of service to paleontology."

Cosmoselachus is one of many well-preserved fossil sharks from the oil-bearing Fayetteville Shale formation, which stretches from southeastern Oklahoma into northwestern Arkansas and has long been studied for its well-preserved invertebrate and plant fossils. Bronson and her coauthors focus much of their recent research on fishes from this formation, both because of the fossils’ exceptional preservation and their position in time.

“These creatures are part of a recovered ecosystem following a major extinction of fish groups at the end of the Devonian Period,” Bronson said. “So it’s a time of incredible morphological diversity in cartilaginous fishes, including all kinds of weird anatomy we don’t see in modern sharks.”