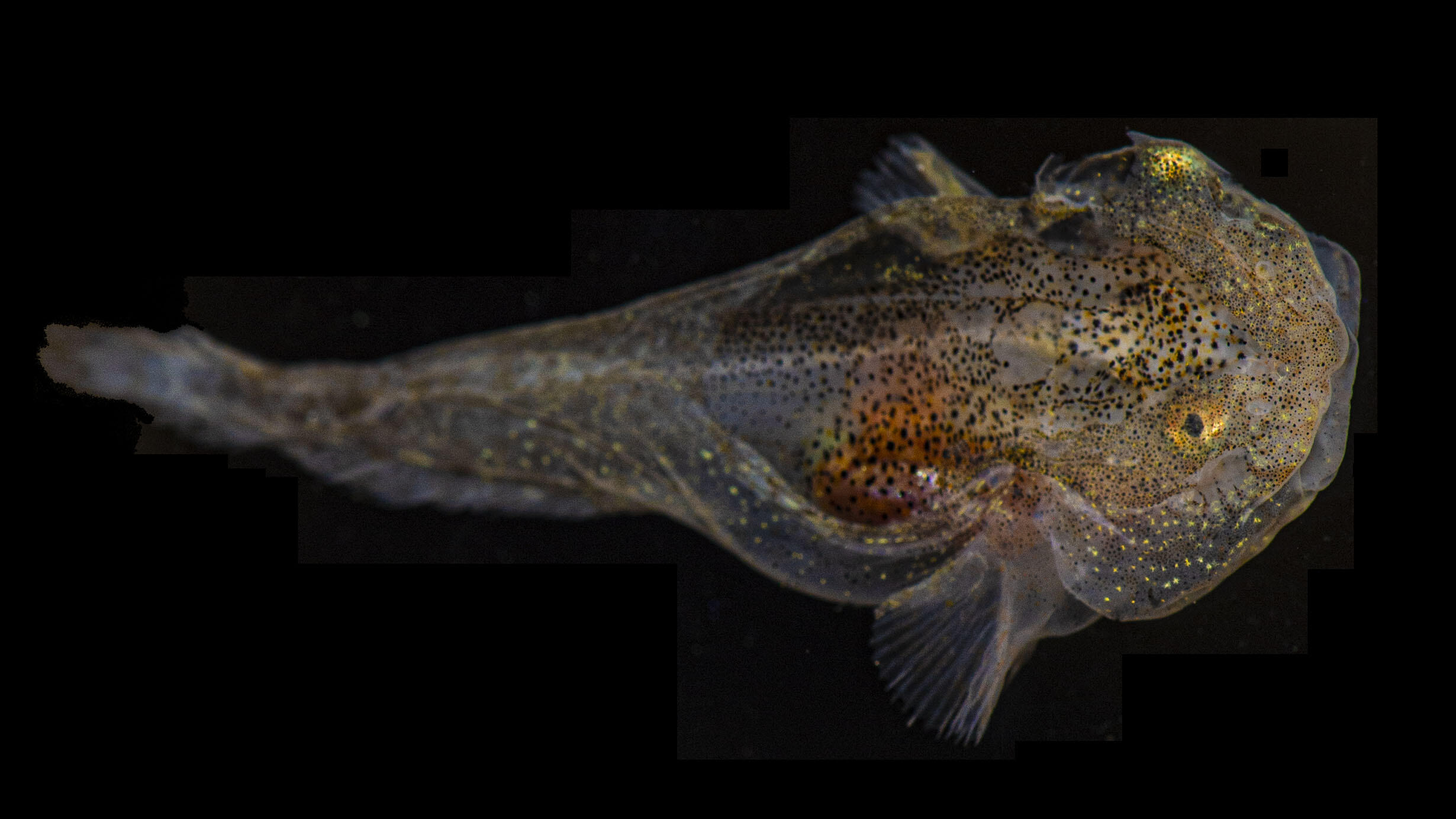

Liparis Gibbus (white light)

Liparis Gibbus (white light)© John Sparks and David Gruber

In 2019, Museum researchers diving in the icy waters surrounding Greenland discovered something unexpected: a small fish glowing in green and red. This glow, or biofluorescence, is an unusual property for fish in the Arctic, where there are prolonged periods of darkness. The tiny snailfish they identified remains the only polar fish reported to biofluoresce. Now, the researchers have uncovered something else surprising about this otherwise unassuming fish: it contains soaring levels of antifreeze proteins.

[ICE RUMBLES]

[The camera flies over a glacier and the water beneath it on a rocky landscape. A small red inflatable boat carries people through floating icebergs.]

[MUSIC]

[SCUBA DIVER 1: Good. Let’s do it.]

[Two scuba divers sit on the edge of the inflatable boat in dry suits meant for cold water.]

[SCUBA DIVER 2: Ready?

SCUBA DIVER 1: One, two, three.]

[The scuba divers flip into the water from the boat with a [SPLASH]. Under water, they descend slowly through turquoise water.]

JOHN SPARKS (Curator, Division of Vertebrate Zoology): So it’s the end of our roughly two-week trip in Greenland,

[SPARKS appears on screen with the rocky icy landscape behind him, wearing sunglasses and a beanie and speaking to camera.]

SPARKS: and I’m sitting, because I can barely stand. This has, without a doubt, been the toughest trip,

[The inflatable Zodiac boat navigates through iceberg-filled water.]

SPARKS: –expedition I’ve ever been on.

[Scuba divers swim past walls of ice.]

SPARKS: The dives are brutal. They’re exceedingly cold… It’s crazy, in a way.

[Title appears: Exploring Greenland’s Icy Waters. Constantine S. Niarchos Expedition 2019.]

[SPARKS stands on a small iceberg looking out at glaciers.]

SPARKS: My name is John Sparks and I’m a curator of ichthyology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

[SPARKS is standing on a small ice floe next to DAVID GRUBER.]

DAVID GRUBER (Research Associate, Division of Vertebrate Zoology): My name is David Gruber. I am a marine biologist here at the American Museum of Natural History–

[GRUBER sits on the edge of a boat as the Greenland landscape flies by.]

GRUBER: –and a professor of biology at Baruch College, City University of New York.

[The scientists sit on the boat as it navigates through icy water with a glacier in the background.]

SPARKS: And we were on an expedition to look at the prevalence of biofluorescence in the Arctic.

[A fish with glowing green stripes on its head swims slowly below a glowing green coral. Text appears: Solomon Islands.]

GRUBER: Biofluorescence is the process of animals absorbing blue ocean light

[Scuba divers point bright blue lights at corals. The video fades to the same video showing the corals glowing green.]

GRUBER: –and transforming that light into other colors.

[GRUBER scuba dives in the tropics, surrounded by coral.]

SPARKS: We had been looking at fluorescence in the tropics,

[Fish swim in and out of a coral reef.]

SPARKS: where you get pretty much year-round even amounts of daylight and dark, so we wanted to see if fluorescence was as prevalent, or as common,

[Timelapse of the sun over snowy mountain peaks.]

SPARKS: –in areas where there are very different amounts of daylight. At certain times of the year in polar regions,

[SPARKS appears on screen in the Museum’s collections space, speaking to camera. Text appears: “John Sparks, curator, Division of Vertebrate Zoology.”]

SPARKS: you get sunlight 24 hours a day and other parts of the year, it’s dark all the time.

[GRUBER appears on screen in the Museum’s collections space, speaking to camera. Text appears: “David Gruber, research associate, Division of Vertebrate Zoology.”]

GRUBER: Yeah, it was a little bit like a detective story. We were sitting

[GRUBER and SPARKS are sitting next to each other in the collections space, while GRUBER talks to camera.]

GRUBER: –over a coffee here in New York where like, “I wonder, how does that effect animals underwater when there’s 24-hour light,

[The sunlight refracts in the cold waters of Greenland.]

GRUBER: some parts of the year,

[A scuba diver swims in pitch black water at night, lit only by a blue light in front.]

GRUBER: and zero light other parts of the year. And we were surprised that no one had looked.

[GRUBER and SPARKS scuba dive in full drysuits among kelp forests.]

SPARKS: We targeted Greenland because there were groups there,

[A scorpion fish pokes its head out of some kelp.]

SPARKS: like the scorpion fishes, that we found elsewhere that fluoresce.

[SPARKS captures a scorpion fish with a net.]

SPARKS: So we could directly compare it to tropical or temperate regions.

[An illustrated map of the East coast of North America appears, with a star showing New York City. A plane takes off from New York City and lands in Reykjavik, Iceland.]

SPARKS: For this trip we had to fly to Iceland first,

[Another plane icon takes off from Iceland and lands next to Kulusuk, Greenland.]

SPARKS: and then we took a small plane to Kulusuk on the east coast of Greenland

[The world map zooms in to just a tiny coastal part of Greenland containing Kulusuk.]

SPARKS: and they have just a tiny airport there.

[A dashed line with a boat leaves from Kulusuk and ends to the West of Kulusuk at Tasiilaq. Under the map, we see faint aerial footage of Tasiilaq.]

SPARKS: And from there, we took about a two-hour boat ride to Tasiilaq, and that was our first diving site.

GRUBER: We did a lot of interesting day dives around there,

[A dashed line with a boat leaves from Tasiilaq and goes north and west up the coast to a place labelled “Ice Camp.”]

GRUBER: but when we went another few hours out to this really remote ice camp

[The map fades away to reveal aerial footage of the ice camp with just a handful of small colorful huts.]

GRUBER: where we had a cove that we could just dive any time we want.

[SPARKS wades into the water from the shore in full diving gear, carrying his fins and a collection bag. In a different scene, he stands on the zodiac boat, looking at the shore.]

SPARKS: As soon as we got to Greenland, we realized, “Boy, we might be in over our heads.”

[GRUBER puts on a dry diving suit on a dock.]

SPARKS: “This is really cold. Whose idea was this?”

[SPARKS and GRUBER appear on screen in the Museum collections, speaking to camera.]

GRUBER: Yeah, it was one thing sitting in a nice, cozy little café in New York and just kind of pondering these topics

[SPLASH]

[GRUBER diving in Greenland over seaweed and kelp, holding his hands stiffly in front of him.]

GRUBER: and then, once we’re in the water in 30 minutes my hands were just freezing.

[SPARKS scuba dives and picks something off a rock to put in his collection net.]

SPARKS: As soon as you get under your face gets numb. And you’ve got very limited time to do your work because of the cold.

[SPARKS appears on screen speaking to camera.]

SPARKS: I mean, it just burns.

[GRUBER turns in the water while diving among kelp, and holding a large underwater camera.]

GRUBER: I actually got frostbite in my fingers, but I want to stay longer because, it’s like, we went through so much effort to get out here.

[The small huts of the ice camp as viewed from the water’s edge. SPARKS and GRUBER appear on screen in the ice camp, giving a tour to the camera.]

SPARKS: This is our ice camp.

[Aerial footage of the ice camp with icebergs in the water behind.]

SPARKS: We’ve got our huts here that we sleep in.

[SPARKS and GRUBER take photos of something in a tank.]

SPARKS: We’ve got a makeshift lab we’ve set up in a storage room.

[CAMERA FLASHES.]

[A photo of a green fluorescent shrimp.]

[SPARKS: That’s good.

GRUBER: Really nice.]

[Another aerial view of the ice camp. Water trickles down a small stream.]

GRUBER: Yeah, we’ve got fresh water coming here from the glacier.

[GRUBER and SPARKS continue their tour of the ice camp.]

SPARKS: And it’s delicious. These are our dry suits that made diving possible here.

[SPARKS dives into a kelp forest below the water. Scenes from below the water: an undulating jellyfish, kelp fronds waving slowly, a school of tiny shrimp.]

SPARKS: There was so much kelp! Kelp with the enormous fronds and there’d be little fish swimming, or shrimp, lots of shrimp swimming amongst the kelp.

[A school of shrimp swimming with a scuba diver swimming behind them.]

SPARKS: It was very beautiful underwater.

[A hermit crab pokes its head out of its shell. Lots of anemones sitting underneath kelp fronds. A tube worm retracts its fronds into a hole. Kelp fronds ripple in the water.]

GRUBER: On land, there’s almost nothing living, like nothing dares to grow more than a foot off the ground up there,

[A ghostly white nudibranch on a kelp frond. GRUBER films with an underwater camera among the kelp.]

GRUBER: but all the life is really in the ocean. We did dives in several different habitats.

[GRUBER appears on screen in front of the rocky Greenland landscape, speaking to camera.]

GRUBER: We looked in fjords,

[SPARKS and GRUBER dive among kelp.]

GRUBER: we looked in the kelp forest, and in several of the dives

[The small boat navigates between icebergs. SPARKS and GRUBER dive next to a wall of ice.]

GRUBER: we actually looked for specimens in the ice, among the icebergs.

SPARKS: What’s really interesting about these icebergs is that they are a refuge for lots of little creatures.

[SPARKS tries to catch a small fish swimming above the ice shelf of an iceberg.]

SPARKS: Crustaceans live right among the icebergs. There’s even fish that kind of dart in among the crevices of the iceberg.

[SPARKS and GRUBER dive on top of an iceberg. The camera comes out of the water to show the tip of the iceberg looming above.]

SPARKS: So they’re like floating habitats for lots of these arctic creatures.

[Camera flies over towering icebers.]

GRUBER: We would have to position ourselves on the part of the icebergs

[GRUBER appears on screen in front of the rocky Greenland landscape, speaking to camera.]

GRUBER: –that didn’t have a chance of ice falling on top of us.

[SPARKS and GRUBER dive in drysuits on top of an ice shelf from an iceberg.]

SPARKS: We got a warming when we got back to the boat on one dive that we were too close. And—but, you can’t—underwater you can’t tell. It was like,

[Scientists pass giant icebergs in a red Zodiac inflatable boat.]

SPARKS: “That was kind of dangerous. You were pretty close there.”

[SPARKS reappears on screen, speaking to camera from the Museum’s ichthyology collections space.]

SPARKS: We both didn’t know what to expect. I mean, in general, we both thought there would be less fluorescence there just because–

[Blue dive lights cut through the black water at night, illuminating corals and kelp.]

SPARKS: –for a large portion of the year, there’s not enough ambient light to stimulate

[A flash, and then we see what the kelp looks like with a fluorescent filter: bright fluorescent red, surrounded by green water.]

SPARKS: fluorescence in these organisms, so it would be of no use.

[SPARKS reappears on screen, speaking to camera from the Museum’s ichthyology collections space.]

SPARKS: But then when we got up there, I thought, “Eh, we’d find it just as much as anywhere else,” But we didn’t.

[We see what the underwater world looks like with a fluorescent filter. Kelp is red while the water is neon green.]

SPARKS: Groups that we found all fluorescence members elsewhere,

[Fluorescent green corals with a fluorescent red scorpion fish. Text on screen: “Solomon Islands, Scorpaenopsis papuensis.]

SPARKS: like scorpion fishes–

[A new scorpionfish appears, from footage in Greenland. It appears a dull grey on top of bright red kelp – it does not fluoresce red like the other scorpionfish. Text appears: “Greenland. Myoxocephalus sp.]

SPARKS: –not a single member up there was fluorescent, which really was kind of startling.

[Footage from the Solomon islands show fluorescent bright green corals and anemones.]

GRUBER: In the tropics, almost all hard corals are fluorescent. Many of the anemones are fluorescent and when we get to Greenland,

[Scuba divers swim at night with a blue light – nothing is illuminated below them.]

GRUBER: there’s almost zero and that’s interesting.

[GRUBER and SPARKS in the dark of their laboratory with a blue light pointing at a fish tank, as they prepare to photograph it for fluorescence.]

[SPARKS: Lights off.

CAMERA FLASH]

[A fluorescent green fish swims through the frame.]

[GRUBER: Oh. Look at that, John. Ok let’s take one more with the white light.

CAMERA FLASH]

[Still photographs of fluorescent green animals, including snails and shrimp.]

SPARKS: There are cases of things that are fluorescent. They’re very beautiful, but they’re few and far between.

[ICE RUMBLING]

[Camera flies over a landscape of gigantic icebergs.]

GRUBER: You know, Greenland is really discussed a lot in the news, it being a kind of Ground Zero of climate change or of change.

[GRUBER reappears on screen, speaking to camera from the Museum’s ichthyology collections space.]

GRUBER: Really, the fluorescence became one part of the research, but I think the broader thing will be–

[A fish swims among fluorescent kelp. Two fish swim in the icy blue waters of Greenland.]

GRUBER: –as the waters begin to warm, are there new fish coming in that didn’t used to be there.

[Anemones reach tentacles out into the water of Greenland.]

GRUBER: We don’t even really understand fully yet what exactly it is we’re losing.

[SPARKS dives among kelp with a collection net, looking for fish.]

SPARKS: It’s just such a cold, unexplored environment. We felt like a lot of these places, we were the first people ever to dive underwater. And that’s kind of cool in a way.

[A large school of shrimp drifts over the kelp beds.]

SPARKS: You know, just look at these habitats that very few people have seen.

[SPARKS and GRUBER scuba dive on top of the ice shelf of an iceberg, as seen from the air, while the inflatable red zodiac floats nearby.

GRUBER: What I love about this is that it was really pure, pure exploration. It was just John and I and a small boat in some of the most far-flung, difficult-to-get-to places. It was—you know—I’ve been diving for several decades and it felt like it was just totally new.

[Credits roll]

The Constantine S. Niarchos Expedition featured here was generously supported by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

Producer

Lee Stevens

Executive Producers

Erin Chapman

Eugenia Levenson

Camera

Peter Kragh

Additional Camera

AMNH / L. Stevens

AMNH / K. Corben, D. Gruber, V. Pieribone, J. Sparks

Editor

Sarah Galloway

Animation / Motion Graphics

Lee Stevens

Images / Archives

David Gruber

John Sparks

Pond5 / Erectus

Music

“Stopping Time” Richard Dutnall (PRS) and Ben Howells (PRS) /

Warner/Chappell Production Music

“A Soft Heartbeat” Richard Dutnall (PRS) and Ben Howells (PRS) /

Warner/Chappell Production Music

“Subtle Story” Richard Dutnall (PRS) and Ben Howells (PRS) /

Warner/Chappell Production Music

“Electronic Organic” Richard Dutnall (PRS) and Ben Howells (PRS) /

Warner/Chappell Production Music

Sound Effects

Freesound / HDVideoGuy, Inplano, jeo, kyles, soundmanfilms, Suz_Soundcreations, tomtenney

©American Museum of Natural History

“Similar to how antifreeze in your car keeps the water in your radiator from freezing in cold temperatures, some animals have evolved amazing machinery that prevent them from freezing, such as antifreeze proteins, which prevent ice crystals from forming,” said David Gruber, a research associate at the Museum and a distinguished biology professor at Baruch College, City University of New York, and a co-author of the study, published today in the journal Evolutionary Bioinformatics. “We already knew that this tiny snailfish, which lives in extremely cold waters, produced antifreeze proteins, but we didn’t realize just how chock-full of those proteins it is—and the amount of effort it was putting into making these proteins.”

Unlike some species of reptiles and insects, fishes cannot survive even partial freezing of their body fluids, so they depend on antifreeze proteins, made primarily in the liver, to prevent the formation of large ice grains inside their cells and body fluids. The ability of fishes to make these specialized proteins was discovered nearly 50 years ago, but the genes of the fish examined in this study, the juvenile variegated snailfish (Liparis gibbus) have the highest expression of antifreeze proteins ever observed.

The researchers, who started this work as part of a Constantine. S. Niarchos Expedition, say this discovery underscores the importance of antifreeze proteins to life in sub-zero temperatures. It also sends up a red flag about how these highly specialized animals might fare in warming environmental conditions.

Read about a different type of fish adaptation in Antarctic waters.

“Since the mid-20th century, temperatures have increased twice as fast in the Arctic as in mid-latitudes and some studies predict that if Arctic sea ice decline continues at this current rate, in the summer the Arctic Ocean will be mostly ice-free within the next three decades,” said co-author John Sparks, a curator in the Museum’s Department of Ichthyology. “Arctic seas do not support a high diversity of fish species, and our study hypothesizes that with increasingly warming oceanic temperatures, ice-dwelling specialists such as this snailfish may encounter increased competition by more temperate species that were previously unable to survive at these higher northern latitudes.”