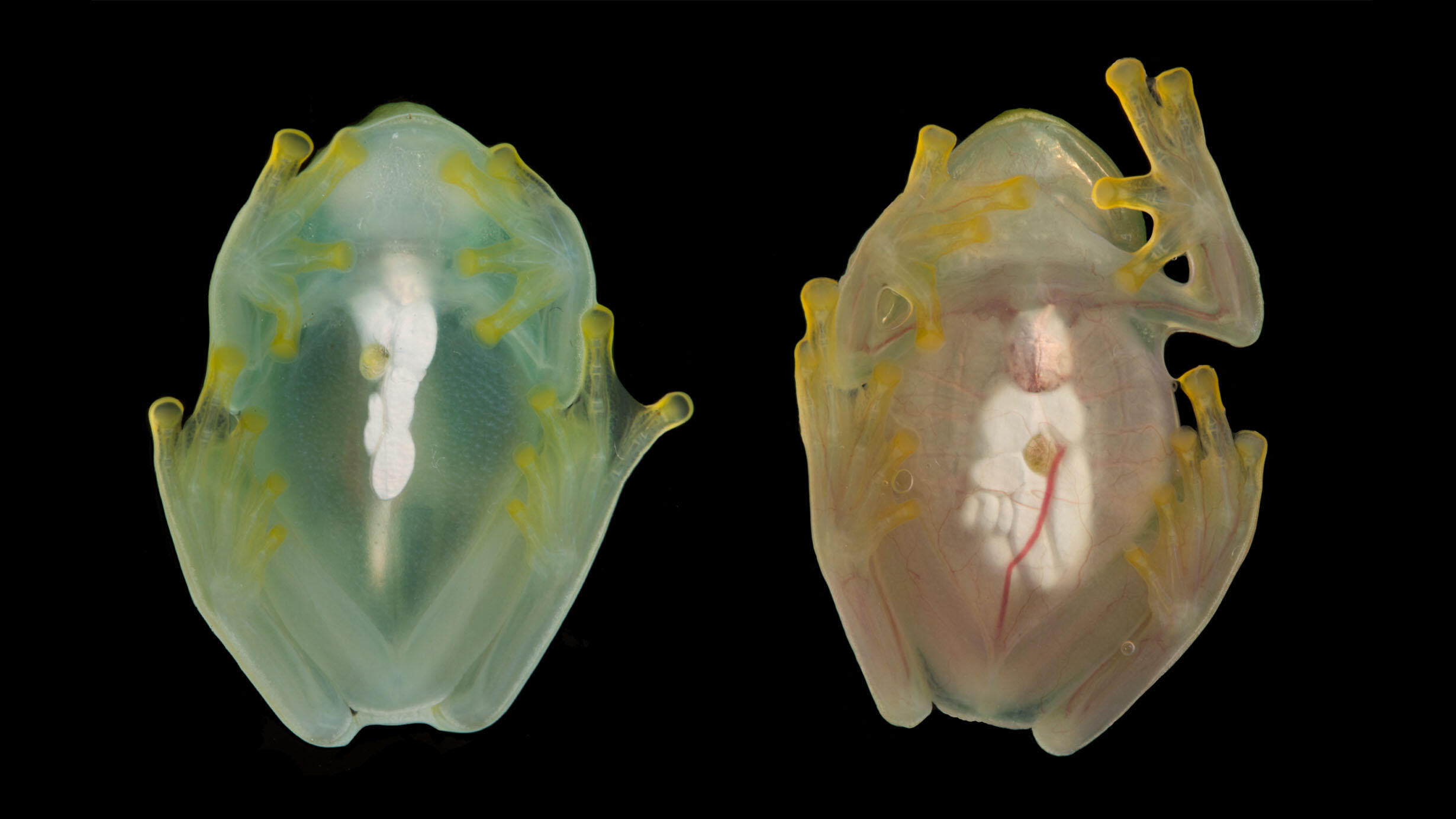

Glassfrog photographed during sleep and while active, using a flash, showing the difference in red blood cell perfusion within the circulatory system.

Glassfrog photographed during sleep and while active, using a flash, showing the difference in red blood cell perfusion within the circulatory system. © Jesse Delia

Glassfrogs, nocturnal amphibians named for their see-through bellies, attain a special type of camouflage by temporarily storing nearly all of their red blood cells in their reflective livers, according to a new study published in the journal Science this week.

And despite packing and unpacking red blood cells into a small space on a daily basis, the frogs don’t experience potentially dangerous clotting—an exciting finding that opens the door for biomedical research.

“There are more than 150 species of known glassfrogs in the world, and yet we’re really just starting to learn about some of the really incredible ways they interact with their environment,” said the study’s co-lead author Jesse Delia, a Gerstner postdoctoral fellow in the Museum’s Department of Herpetology.

Transparency is a common form of camouflage among aquatic animals—for example, in ice fish and larval eels—but it’s rare on land. For vertebrates, accomplishing transparency is difficult because their circulatory system is full of red blood cells that interact with light. Yet glassfrogs have found a way to mute this telltale trait.

Native to the American tropics, glassfrogs spend their days sleeping upside down on translucent leaves that match the color of their backs. Their undersides have translucent skin and muscles that allow their bones and organs to be visible, an adaptation that masks the frogs’ outlines on their leafy perches and makes them harder for predators to find.

© Jesse Delia

To investigate how they achieve their rare transparency, researchers used a technique called photoacoustic imaging at Duke University. The method uses light to induce sound-wave propagation from red blood cells, allowing the team to map the cells’ location within sleeping frogs without using restraint, contrast agents, sacrifice, or surgery.

The team found that resting glassfrogs increase transparency two- to threefold by removing nearly 90 percent of their red blood cells from circulation and sequestering them within their liver, which contains reflective guanine crystals that shield the cells from light. When the frogs become active again, they bring the red blood cells back into the blood.

In most vertebrates, aggregating red blood cells can lead to potentially dangerous blood clots in veins and arteries. But glassfrogs don’t experience clotting, which raises significant questions for biological and medical researchers.

“This is the first of a series of studies documenting the physiology of vertebrate transparency, and it will hopefully stimulate biomedical work to translate these frogs’ extreme physiology into novel targets for human health and medicine,” Delia said.