Shelf Life 08: Voyage of the Giant Squid

NEIL LANDMAN (Curator, Division of Paleontology): In about 1998 or so, I put out an APB around the world to see if anybody could find a giant squid.

Because I study ancient organisms, but I’m also interested in their modern cousins.

I think it was just toward the end – about ’98, ’99 - I got a phone call that a colleague in New Zealand had just found a giant squid and would I be interested. And my answer was, “Absolutely.” As I got off the phone I wondered what I had just agreed to because how am I going to get this giant squid from New Zealand into the portals of the American Museum of Natural History.

My name is Neil Landman. I’m the Curator-in-Charge of Invertebrate Paleontology.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

MARK SIDDALL (Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): The giant squid is among the largest invertebrates on the planet. They get to that size from something very, very small. In fact, the average size of a giant squid egg is on the vicinity of a millimeter long, total. And then they grow to these enormous things. I think that’s terrifically fascinating.

I’m Mark Siddall, Curator of Invertebrates at the American Museum of Natural History.

The giant squid has captivated people for a very long time. The idea that there are enormous things in the sea that are elusive and can’t be seen very easily is itself fascinating.

But really, giant squid are probably not that rare. Giant squid are in the North Atlantic. They’re in the South Atlantic. They’re in the North Pacific. They’re in the South Pacific. Really, all around the globe, and probably in fairly sensible numbers. Otherwise, what would be feeding all the sperm whales? And sperm whales certainly love to eat giant squid.

Why we haven’t been able to see them so well partly has to do with exploration. They’re not down at the very bottom of the ocean. They’re not right up at the top of the ocean. They’re in those mid-level depths. And, in fact, that’s the part of the ocean that we still need to go and explore in much more detail than we have already.

LANDMAN: This particular specimen is about 30 feet long from tip to tip. It was actually captured by chance, by fishermen off the coast of New Zealand. So, how do you even book passage for a giant squid? I mean, you know, it has to go by air. It was frozen solid.

It was shipped in a refrigerated truck from Wellington to Auckland, where it boarded a flight bound for L.A. It was supposed to make a connection from L.A. to New York and that’s where we began to worry because apparently it missed its connection. I thought, “Oh, it’s just going to melt on some runway and that’s going to be the end of our dream.” Fortunately, it managed to make the next plane out.

When the giant squid arrived at Kennedy Airport, a forklift started bringing it toward us, but then the Customs officials realized that we needed paperwork. You know, this was the first time they had ever had a giant squid delivered. So, there was a lot of consternation. Until the general decision was that we would call this frozen seafood, sushi. They came up with a tariff of $10 to clear it for Customs and we left with the squid in the refrigerator truck.

Back at the Museum, we laid it out as best we could to let it start thawing. It was in really great shape.

I was interested in comparing the jaw of the giant squid to the jaws of a fossil cephalopod, from an ammonite. And this animal afforded me the opportunity to study the jaw.

What we realized is we needed to preserve it somehow.

So, we injected the giant squid with formalin and then, now, we had to somehow get it into a bath of ethanol. All together it was several hundred pounds It was a little top heavy. So, you had to really balance it and everybody was to try to get it into the container in one piece. And it worked.

SIDDALL: This is one of the best-preserved giant squids in any collection, anywhere. Now, we’ve known about giant squids going back to the 1500s, in terms of finding specimens. They were first described as Architeuthis dux in the 1800s. Since then we have now had up to 20 or so names for different species of Architeuthis.

But some of these different species of giant squid are from partial specimens usually things that are washed up on shore. We also know about giant squid from the stomach contents of sperm whales. But of course, those are chewed up and really, what we get from those are just the hard parts, like the beak, and maybe some of the suckers. So, having a really well preserved specimen here in the Museum for study is terrifically important.

The giant squid specimen we have here at the Museum—it’s labeled as Architeuthis kirkii. Now, over the course of time, people thought, well, the one from South Africa’s a different species. The one from New Zealand is a different species. The one from the North Atlantic is different from the one from the Pacific. We now know from mitochondrial DNA analysis that, in fact // it all appears to be one species. Given that Architeuthis dux was the very first name for any one of these, it carries priority and thus Architeuthis dux applies to all of the giant squid.

What we need to do on a continuing basis is as the science changes, when we learn new things about synonymy – that, for example, two species are really one species, or the opposite, that one species is really two species, we need to be able to find what it was called before. You actually end up having multiple labels inside the jar. Or in this case, a very large tank.

LANDMAN: For me to look at it for the first time, it was looking into this mythical creature, this sense of seeing something that, you know humans have dreamed about for hundreds of years, here was finally- I was face to face with the giant squid.

For me, to look at it for the first time, it was...this mythical creature. I was face to face with the giant squid.

- Neil Landman, Curator, Division of Paleontology

The Stuff of Legend

This episode of Shelf Life focuses on the very practical problem of transporting a rare giant squid specimen. But long before they were a quandary for customs officials, these mysterious cephalopods fueled folklore all over the world. They’re not alone—many storied beasts took shape around seeds of reality. While they may not breathe fire, heal disease, or crush ships, the animals that inspired their mythological counterparts are no less fantastic.

Release the Kraken

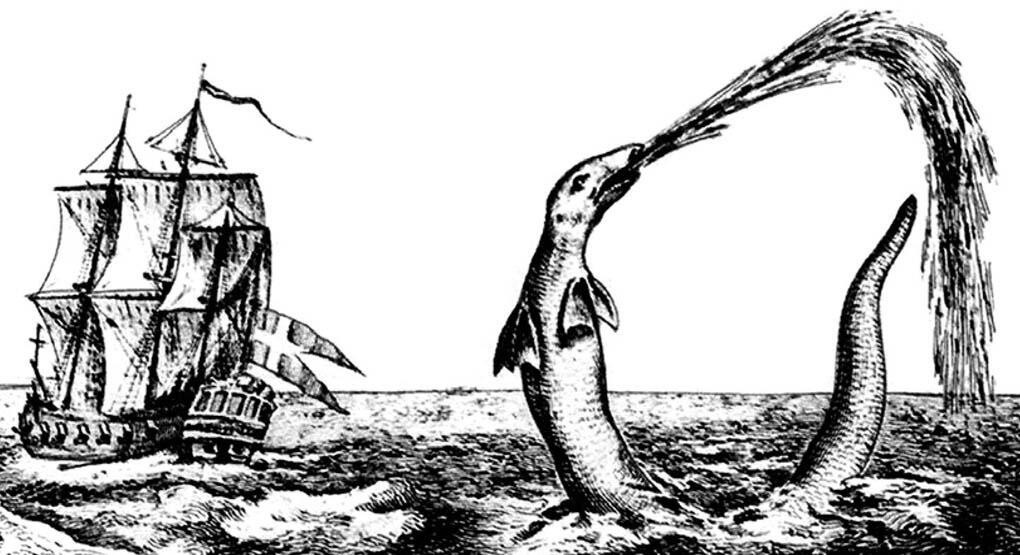

Denizens of the deep have enthralled humans for centuries. Greek myths pitted Hercules and Perseus against the serpentine sea monster Cetus. A 13th-century Icelandic saga told of the sea beast Hafgufa, which swallowed men and ships alike. In 1830, Alfred Lord Tennyson penned a sonnet about the kraken, a legendary Scandinavian sea creature so charismatic that 150 years later Hollywood decided to unleash it on ancient Greece in Clash of the Titans.

These marine monsters may have a basis in fact. Giant squid may not reach the size of the gigantic kraken, which was sometimes depicted demolishing boats with its massive tentacles, but they are formidable and impressive animals. The largest giant squid are thought to measure more than 40 feet from the tips of their tentacles to the end of their mantle, or body. That’s about the length of a school bus.

P. Rollins/© AMNH

Sighting a squid as big as a bus is still a momentous feat. Photos and videos of these benthic behemoths in their natural habitat are rare, headline-making events. So imagine a sighting centuries ago: it would certainly have been exceptional fodder for any seafarer’s stories. And as those tales were shared, the creature likely grew with each retelling, eventually reaching titanic proportions.

In his book The Search for the Giant Squid, marine biologist and Museum Research Associate Richard Ellis speculates that even Greek myths of the many-armed Scylla and the Hydra, one of Hercules’s foes, could have been inspired by glimpses of giant squid.

Since enormous cephalopods usually keep to mid- to deep-water habitats, the most common way to see a giant squid would have been to spot a dead or dying squid that had floated to the surface. These animals’ bodies—long, thin, and utterly strange—may have helped to give life to legends of serpentine sea monsters.

D. Finnin/© AMNH

In Conrad Gesner’s 16th-century Historiae Animalium, for example, the hydra is depicted as having a trunk-like body with many heads, each one sitting on the end of a long, serpentine neck. “[It] is not impossible,” Ellis points out, “to see the ‘heads’ as arms, and the body as that of a large cephalopod.” Lose the feet, and Gesner’s hydra turns out to be a pretty decent depiction of a giant squid.

My, What Big Tooth You Have

The natural world provided plenty of inspiration for other legendary beasts, as the Museum’s 2008 exhibition Mythic Creatures detailed.

Take the unicorn, an iconic creature in Western mythology that also has counterparts in China and Japan. Typically depicted in the West as white horses with long, slender horns rising from their heads, unicorns have inspired artwork for hundreds of years, from medieval tapestries to elementary-school notebooks.

Metropolitan Museum of Art/37.80.6

In the Middle Ages, believers didn’t have to rely on second-hand stories to bolster their faith in unicorns. For a hefty sum, they could purchase long, white, spiraled horns, presented as proof of the wondrous creatures' existence. The majestic horns were said to have magical properties, including the power to cure disease.

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

Unfortunately for medieval shoppers, these horns didn’t come from unicorns. They were harvested from creatures arguably even more fantastic: narwhals, Monodon monoceros, a species of whale. Narwhal males sport an extraordinarily long tusk, which is actually an overgrown left canine tooth that pierces the animal’s upper lip. Researchers have proposed several purposes for these impressive teeth—which can reach more than 9 feet in length—from an acoustic sounding stick to a seafloor spade. In 2014, dentist and Harvard School of Dental Medicine instructor Martin Nweeia, along with a team of colleagues, published a paper suggesting that this tooth is actually a sensory organ that may help males detect changes in salinity, temperature, pressure, and even pheromones released by females who are ready to mate.

NIST/G. Williams

Narwhal horns were not the only thing fueling belief in mythological equines. As Westerners began to expand their trade routes, real-life animals with notable horns on their heads were spotted in the far corners of the world. Around 1300, the Italian explorer Marco Polo recorded this sighting in Sumatra:"There are wild elephants and plenty of unicorns, which are scarcely smaller than elephants. They have the hair of a buffalo and feet like an elephant's. They have a single large, black horn in the middle of the forehead... They have a head like a wild boar's and always carry it stooped towards the ground. They spend their time by preference wallowing in mud and slime. They are very ugly brutes to look at."

In retrospect, it seems clear that Polo had in fact encountered the Sumatran rhinoceros. The animals’ horns may have helped perpetuate the myth of the unicorn, though given the discrepancy between the unicorn’s idealized form and and the reality of the so-called “hairy rhinoceros,” one can forgive Polo his disappointment.

Dinosaurs and Dragons

While specimens from living animals like the narwhal and rhino helped prop up the myth of the unicorn, some stories of mythological creatures were inspired by animals that had long been extinct. For instance, the fossilized skulls of dwarf elephants—which have huge nasal cavities in the center—are thought to have inspired stories of the Cyclops, the one-eyed giant of Greek mythology.

Denis Finnin/© AMNH

Big bones may have also given rise to one of the most enduring creatures of legend: the dragon. These enormous serpents or lizards, sometimes described as having wings and breathing fire, are found in tales across Europe and Asia, a tradition that spans Arthurian legend to contemporary film and television.

Dragon legends were likely inspired, and fueled, by fossil finds. The Austrian town of Klagenfurt for years displayed the skull of an extinct woolly rhinoceros that was fabled to belong to a dragon slain by knights. And pioneering paleontologist Mary Anning may have been the original "Mother of Dragons," securing her reputation as a famed fossil hunter in the 1820s with discoveries of pterosaurs and a complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus, a find made famous in the 1840 title The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons.

D. Finnin/© AMNH

Dragons have been a powerful presence in Chinese culture for centuries, and in traditional Chinese medicine powdered dragon bones are still prescribed as a cure for conditions ranging from madness to dysentery. Most of these “dragon bones,” though, are the fossils of extinct mammals, unearthed from China’s many rich fossil beds.

E. Stanley/© AMNH

The dragon continues to loom large in popular culture, at times inspiring a curious reversal: real species named in honor of legendary monsters. In 2011, while working on his Ph.D. at the Museum’s Richard Gilder Graduate School, biologist Ed Stanley named a genus of girdled lizards found in South Africa’s Drakensberg (that’s Dragon Mountain) range after Smaug, the terrifying, treasure-hoarding dragon of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Stanley says the homage was as much to the author—Tolkien was born in South Africa—as to the fabled beast, but the end result is the same: the storied Smaug is now a real-world lizard.