Shelf Life 09: Kinsey's Wasps

CHRISTINE JOHNSON (Curatorial Associate, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): “Most of us like to collect things, and some of us have quite a dose of that instinct.

Some folks collect stamps, others collect cigar bands or autographs, a pocket full of junk, or dollars and dollars. If your collection is larger, even a shade larger than any other like it in the world, that greatly increases your happiness.”

And that's from Alfred Kinsey in An Introduction To Biology.

My name is Chris Johnson. I'm the collection manager for the Division of Invertebrate Zoology.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

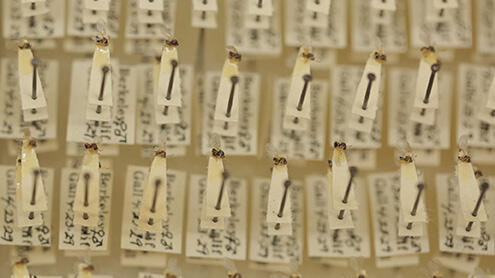

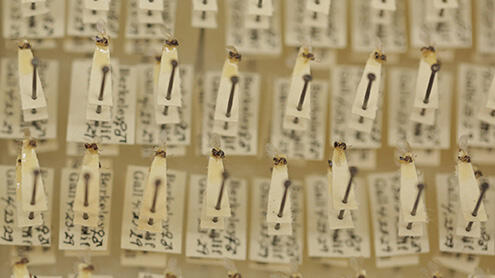

JIM CARPENTER (Peter J. Solomon Family Curator of Hymenoptera, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): We estimate the size of the insect collection at the American Museum of Natural History to be about 18 million. The size of the gall wasp collection is over seven and a half million. So, at seven and a half million specimens, you see that this family is certainly the largest single group.

I'm Jim Carpenter. I'm the Chairman of the Division of Invertebrate Zoology and Peter J. Solomon Family Curator of Hymenoptera.

The primary part of our gall wasp collection is the Kinsey collection.

JOHNSON: Alfred Kinsey was actually a famous sexologist but he was also an entomologist before he studied human sexuality and he collected gall wasps - shelves and shelves and shelves and shelves and shelves.

I have to admit, just myself, I can't imagine how ginormous his operation must have been to do what he did. It's just astonishing.

Kinsey's first scientific paper was published in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History and those associated specimens were already here, so in 1958, after he passed away, his wife donated the bulk of his collection to the Museum.

Kinsey actually traveled throughout the United States, through 36 states, over 18,000 miles, just collecting plant material and then taking that plant material into his lab and then actually reared the wasps from these galls that he collected.

CARPENTER: Now what galls are, are plants' induced tissue. The female lays her eggs into plants and after that, the larva hatches, feeds on the tissue and then the galls are brought about by the plant's response to larval saliva.

JOHNSON: Once you see a gall, and you notice a gall on a plant, you will never not see them again. They can be on leaves, they can be in branches. And if you start looking at galls and you see the incredible diversity, it's just spectacular.

It's- Some of them look like echinoderms, some of them look like fuzzy caterpillars.

CHRISTINE LEBEAU (Museum Specialist, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): Some of them look like bits of fluff. Some of them look like goiters. Some of them can be quite tiny. Some of them can be quite large.

My name is Christine Lebeau. I am a scientific assistant in Invertebrate Zoology.

The Kinsey donation is so large that it hasn't been entirely unpacked. So, we've had volunteers and interns work with us over the years to slowly unpack the remaining boxes.

CARPENTER: Back in Kinsey's time, it was of course part and parcel of insect taxonomy to gather very long series of a single species.

In the case of making measurements of species, which was one of the things Kinsey was doing, well, the more the merrier.

Collections are more useful if there's material from across the entire range of a species because variation in structure, in physiology, and genetics can occur in response to environmental differences.

JOHNSON: One of the good things about having so many specimens is you can look at differences in what is being collected over time. You can correlate it with weather, with temperature, with rainfall.

CARPENTER: Another advantage of the size of this collection, the sheer scale of it, is the possibility of ancient DNA being found. Ancient DNA refers to the DNA in preserved specimens. And the "ancient" is relatively speaking, in this case.

In recent years, with the development of better technology, it's becoming possible to get DNA out of preserved insect specimens. But, particularly for small insects - and we are talking small in the case of the gall wasp - typically, you have to destroy the whole specimen to successfully amplify DNA from it.

But we have such large series of so many of those species that the destructive sampling of some specimens is of no concern.

LEBEAU: We can loan out 10,000 specimens at a time. We recently had someone borrow 10,000 specimens for their PhD project.

New species are being published on. About a year or so ago, a researcher in Spain named a wasp after me. Andricus lebeaue, I believe, is the correct pronunciation.

PRODUCER: What does your wasp look like?

LEBEAU: Small and brown just like the others.

CARPENTER: I certainly started as an insect collector when I was a teenager, in the hopes of making a large insect collection. The larger it is, the more likely it is that you'll have more species. And that makes it more complete.

It's supposed to reflect actual biodiversity of nature in the world.

"The larger [a collection] is, the more likely it is that you'll have more species [and] reflect actual diversity of nature in the world."

-James Carpenter, Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology

First Came the Wasps

Alfred Kinsey is best known for his groundbreaking work in human sexuality, but he came to this made-for-Hollywood specialty relatively late in his career. For the first act of his academic life, Kinsey studied entomology and botany. In particular, he studied gall wasps: tiny, solitary wasps who inject their eggs into plant tissues, inducing growths known as “galls” that provide food and protection to their larvae.

© AMNH

The study of solitary wasps and human coupling may seem like wildly disparate interests. But both subjects provided outlets for what could be said to be Kinsey’s real passion—the accumulation and categorization of huge amounts of data, and the transformation of that data into new knowledge.

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

Kinsey didn’t just study gall wasps: he amassed specimens with unrivaled intensity, creating a collection of more than 7.5 million wasps and their associated galls that now reside in the Division of Invertebrate Zoology of the American Museum of Natural History. In the early years of his studies, Kinsey traveled some 18,000 miles across North America, frequently camping for days while gathering thousands of galls. He would send those back to his lab in Indiana, where assistants would wait for the short-lived adult wasps to emerge. He eventually collected specimens from 36 states and numerous locations in Mexico, and compiled a collection from all over the world.

Big collections aren’t just a feather in a researcher’s cap, though. Large series of specimens offer scientists more opportunities to answer more questions about a species, and big sample sizes make it harder for outliers—individuals that are very large or very small, for instance—to skew results. Collections on a scale like Kinsey’s need to be made responsibly, of course, and not damage wild populations. But they can also be valuable conservation tools, serving as snapshots of big trends that allow researchers to track shifts over time and place and see how populations react in response to factors like environmental change.

©AMNH

©AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

Kinsey's drive toward collecting more and more specimens wasn’t purely a scientific pursuit—it was a personal passion as well, and a subject on which the generally reserved researcher was inclined to wax poetic. In a biology textbook he penned, Kinsey elaborated on his voracious appetite for new specimens:

"If your collection is larger, even a shade larger, than any other like it in the world, that greatly increases your happiness. It shows how complete a work you can accomplish, in what good order you can arrange the specimens, with what surpassing wisdom you can exhibit them, and with what authority you can speak on your subject."

While analyzing his growing gall wasp collection, Kinsey demonstrated his penchant for big data and honed some of the methods he would refine in his study of human sexuality. For example, Kinsey took up to dozens of measurements on each of his wasp specimens—no small feat when you consider that even the largest specimens only grow to be 8 millimeters long. He meticulously recorded the data on sheets and sheets of graph paper, covered in notations, and later in his entomological research developed a system of coded entry.

© AMNH

He carried this experience encoding data into his work on human sexuality, where it allowed him to distill hour-long interviews detailing an individual’s entire sexual history to a handful of lined cards.

In the midst of his gall wasp studies Kinsey, then a professor of entomology at Indiana University, began teaching the “marriage course” in 1938. The class sought to prepare students for marriage by teaching them the facts about sex and sexuality. There was just one problem—there was a startling dearth of facts available in scientific literature.

Kinsey took it upon himself to fill this gap, conducting interviews with students in the marriage course that became the first data in his career as a sexologist. He would spend the remainder of his life in the field, producing a series of groundbreaking , and often controversial, publications.

Bringing his entomological training to bear on his new specialty, Kinsey treated his research into sex as biological fieldwork and approached it with the same diligence and dedication that drove his collection of wasp specimens and galls. His interviews with subjects were wide-ranging and meticulously documented. He was also famously, or perhaps infamously, nonjudgmental about the behaviors reported by participants in his research, analyzing sexual behavior with a scientific methodology.

There were some adjustments, of course. Rather than the straightforward data encoding used for his wasps, Kinsey sought the help of a professional cryptographer to develop the code for his studies in human sexuality. Nearly everything was coded for in Kinsey’s study, from the age, sex, and weight of the subjects to how excited they were by risque jokes and what kinds of music they listened to during lovemaking. Since the research was conducted largely during the 1930s, there was, alas, no code for “Barry White.”

Whether studying gall wasps or humans, Kinsey also recognized the importance of gathering information from a variety of subjects. This meant extensive travel, just as it had when he was collecting his insects. Interviews for his sexuality studies began at Indiana University in Bloomington, but eventually ranged far and wide, taking Kinsey across the country from coast to coast to collect sexual histories from prisoners, college students, and people from all walks of life. He had an insatiable drive to collect data: while on the lecture circuit for his first major book, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey frequently turned down speaking fees and instead asked his hosts to arrange for him to collect more histories while he was in town.

During his lifetime, Kinsey’s work on sexology produced two books based on his interviews with more than 11,000 individuals; three more drawing from his data were published posthumously. These bestsellers changed how the world viewed what happens behind closed doors. But the techniques that made this momentous work possible were developed and refined while studying the humble gall wasp.