Shelf Life 02: Turtles and Taxonomy

DARREL FROST (Curator, Department of Herpetology): The easiest way of describing what we do is we document the distribution of animals. And so, this collection of reptiles and amphibians is one of the largest in the world. It’s about 300,000 specimens.

My name is Darrel Frost. I’m a curator in the Department of Herpetology.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

FROST: People in pre-literate societies have enormous memories. People would recite the Iliad and they would go on for days at a time. [sings rhythm]

NARRATOR: [Greek line from the Iliad]

FROST: And they could remember it. And our brain is organized in a way that we can handle a lot of structured knowledge.

And it’s because you can store it. And that’s why we have taxonomy—so we can organize the world around us. And the collections actually are organized in that way, as well.

The turtles are all here together. They’re not arranged chronologically. They’re arranged by what they’re related to. So, since you have other kinds of structured knowledge in your head as you’re looking at them the structure of the collections themselves actually helps in the formulation of questions.

Most of us who are actually in science have been around these things since we were in undergraduate school or in high school in some cases. So, we’re used to them.

The wonder part of it isn’t so much in the objects anymore as in the relationships and what they tell us in a sophisticated way. You know, it’s- it’s kind of a clarinet.

When you think about how it’s put together and how it works, that’s pretty wondrous, but it’s not as wondrous as the music that comes out of it. And so, that’s the thing about collections. At first blush, it’s pretty wonderful stuff, but what it tells you is even better.

It documents life on earth and human cultures. And it documents it in a way that it’s this ever increasing effluence of information coming out of this set of objects. Like, in 1880, they weren’t thinking about DNA. So, the questions change.

Collections tell you about the past. But knowing about the past learning about how things are structured and how they work you can predict what the future’s going to bring.

That's the thing about collections—at first blush, it's pretty wonderful stuff, but what it tells you is even better.

-Darrel Frost, Curator, Division of Vertebrate Zoology

A Brief Yet Discerning History of Scientific Classification

From humanity’s earliest days, we’ve been pretty intent on naming and classifying things. After all, without words like “banana” or “tiger,” it would be difficult to ask important survival questions like “Are bananas good to eat?” and “Can a tiger outrun me?” But after we moved on from hunting, gathering, and escaping large carnivores, names became the lexicon that allowed more complicated investigations. To understand things, we have to name them and group them—and then we get to start asking questions about the world.

Humans have left records of such inquiries since antiquity. For a quick look at how scientific classification evolved in the Western world, we turned to the Museum’s Research Library and picked up six volumes representing some key steps along the way. (For the 21st-century highlight, we went, of course, to the internet—and to the work of some of our own scientists to bring new research tools online.)

Aristotle

The great Greek philosopher Plato believed the world as perceived by our senses was but a shadowy and incomplete version of the truth. His brilliant student, Aristotle, had other ideas. He said that nature could only be understood through observation, analysis, and classification.

Aristotle’s De historia animalium divided animals into those with and without blood—roughly corresponding to modern categories of vertebrates and invertebrates. He classified animals using hierarchies and relationships, forging the way for future biologists to try to organize nature as they saw it.

Gessner

D. Finnin/© AMNH

Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium—an immense 16th-century work that attempted to catalog all known animals—organized species not by any systematic scientific classification, but in alphabetical order. That might not seem like particularly rigorous biology, but, to his credit, Gessner also included details on nomenclature, distribution, and behavior—and tried to group animals based on broad characteristics, such as number of limbs or if they were land- or water-dwellers.

Aldrovandi

Gessner’s contemporary, the Renaissance naturalist and philosophy professor Ulisse Aldrovandi, is known for assembling a spectacular teatro della natura, one of history’s most famous “cabinets of curiosity.”

via Archive.org

But Aldrovandi didn’t just collect; he categorized. He wrote influential volumes on animal classification, borrowing heavily from Gessner, but with a more scientific approach to organization. His Ornithologiae classified birds based largely on habitat and behavior, rather than anatomical features. Groupings included birds with powerful beaks, birds that bathe in dust, and even a section on bats.

C. Chesek/© AMNH

Hooke

When English naturalist Robert Hooke used an early microscope to produce detailed illustrations for his 1665 work Micrographia, he opened a portal into a previously invisible world.

D. Finnin/© AMNH

It is the minuscule writ large: the whiskery legs of a flea, dainty stalks of bread mold, and a seemingly enormous louse clinging to a single strand of human hair. Scientists suddenly had an abundance of new organisms to classify. They also had a new word to deploy: Micrographia includes the first recorded use in biology of the word “cell,” which Hooke used to describe the pattern he observed on a thin slice of cork.

Linnaeus

Little Carl Linnaeus might have been great at fantasy football (or, being Swedish, fantasy fotboll). But instead of mastering stats, he memorized plant names, a particularly difficult task at the time given that plants had elaborate Latin names. The tomato, for example, was called Solanum caule inermi herbaceo, foliis pinnatis incises (“solanum with the smooth stem which is herbaceous and has incised pinnate leaves.”)

R. Mickens/© AMNH

Despite this verbosity—or perhaps because of it—classification fascinated Linnaeus throughout his life. He developed the system of binomial nomenclature—formally assigning two names to each species—that is still in use today, and he popularized rank-based classification (the kingdom, phylum, class, order structure that you may have learned in grade school). The tenth edition of his Systema naturae, published in 1758, contains descriptions and the first scientific names of some 4,400 animals ranging from the narwhal to the dodo.

Haeckel

A popularizer of the then-recent theory of evolution, German biologist Ernst Haeckel helped put Charles Darwin on the map. His 1866 illustration in Generelle Morphologie der Organismen is often cited as the first published depiction of a phylogenetic tree of all life—a map of the evolutionary development of species.

Roderick Mickens/© AMNH

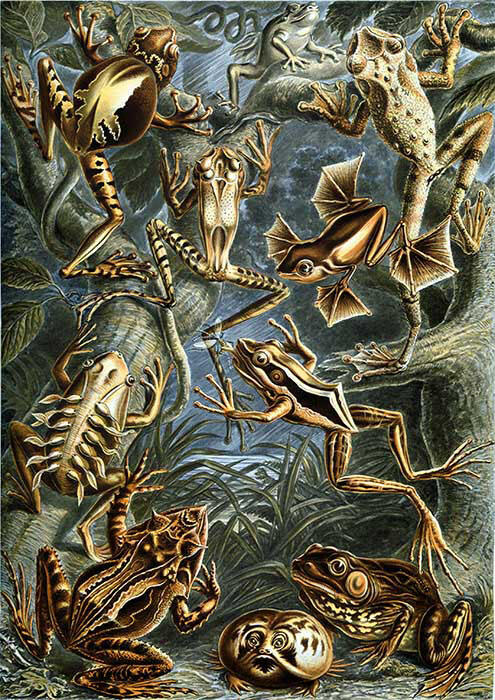

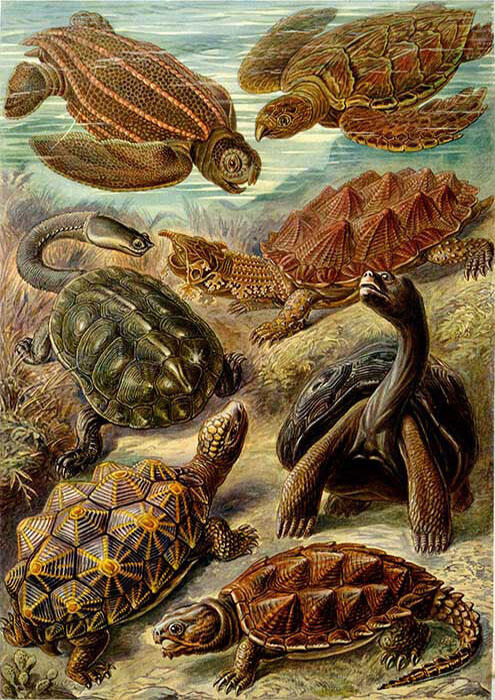

Haeckel is also known for his visually stunning Kunstformen der Natur and for his formulation “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” (the idea, since rejected in biology, that as embryos develop, they pass through stages of evolution.

Ernst Haeckel was well known as a taxonomist even before he published his striking illustrations in Kunstformen der Natur (1899-1904).

Ernst Haeckel was well known as a taxonomist even before he published his striking illustrations in Kunstformen der Natur (1899-1904).Courtesy of Wikipedia

Hennig

Willi Hennig, who was trained as an entomologist, outlined the biological classification method called cladistics in Theorie der phylogenetzschen Systematik (1950).

This approach uses shared derived characteristics—that is, characteristics found in members of a particular group (say, hominids) but not in the larger group of related animals (great apes)—to group organisms and gives insights into the distribution and diversity of life on Earth. Unfortunately, the first edition in German was largely ignored, and few scientists understood the implications for taxonomy until the work appeared in English in the mid 1960s.

21st Century Taxonomy

Just as microscopes opened new worlds for Hooke, technology is unlocking new lines of research for today’s taxonomists. Web-based technology and advances in DNA analysis now support online databases for classification and systematics. The web application MorphoBank recently allowed Museum researchers and their colleagues to build a new tree of life for mammals and in the process, reconstruct the common ancestor of all placental mammals.

This new technology comes at a turning point, as there is a renewed urgency for taxonomic work. For all the centuries we’ve spent classifying life, we’re now presiding over a great extinction event. There are potentially 8 million species on Earth, and researchers have only described about 1.5 million. Many will go extinct before we can even give them fancy Latin names. In the face of this biodiversity crisis, taxonomists are trying to record life as it disappears—and perhaps help save some species along the way.

Curator Darrel Frost created and manages Amphibian Species of the World, an online database listing all scientific and English names for more than 7,000 amphibian species. While the database was designed for professional systematists—lots of text, no pretty pictures—it gets more than a million visits a year from scientists, conservationists, and policymakers. Frost says it’s become, “a unifying influence for conservationists to talk to one another.” Organizations such as CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) and the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) use the database in trade regulation of amphibian species and to inform habitat conservation efforts around the world.