Nabokov's Butterflies Shelf Life 360

SHELF LIFE 360 – NABOKOV'S BUTTERFLIES

Visual Cue Transcript

[TRAFFIC, HORNS HONK, SUBWAY TRAIN RATTLES]

American Museum of Natural History Logo appears as scene fades up on a collage of 1940s New York City.

SUZANNE RAB GREEN: In the summer of 1941, the writer Vladimir Nabokov set across on a road trip of North America, driving by car 4,000 miles, all the way to California.

[TINNY SWING MUSIC PLAYS ON A CAR RADIO]

A highway expands across the scene. The cityscape dissolves into a collage of 1940s motor courts, diners, and roadside attractions. An animated Pontiac drives through the scene.

The landscape darkens and a giant moon rises over the scene.

RAB GREEN: He usually stopped every night at some roadside motel—

[DESK BELL RINGS]

RAB GREEN: scruffy little places.

[COYOTE HOWLS]

RAB GREEN: And these places became the setting of his famous novel, Lolita.

Neon signs glow and are surrounded by numerous fluttering moths.

[FLAPPING WINGS, BUZZING NEON SIGN]

RAB GREEN: But these locations were also the setting for his butterfly collecting.

Buildings fade away, leaving giant stacks of books by and about Nabokov along the roadside. The landscape is covered in Nabokov's handwriting. Dozens of butterflies flap around.

[WING FLAPS, PENCIL SCRIBBLING ON PAPER]

RAB GREEN: For most people, Nabokov is very famous as a writer, but not many people actually knew he was an avid, passionate lepidopterist. He liked to collect butterflies.

Scene dissolves into Suzanne Rab Green sitting on a stool in the middle of the butterfly and moth collections room. There are open drawers showing numerous tiger moth specimens. Rab Green speaks to the camera.

RAB GREEN: My name is Suzanne Rab Green. And I'm a curatorial assistant for Lepidoptera, and here we are in the collections where I study moths and butterflies.

[MUSIC WITH PLUCKING STRINGS]

RAB GREEN: And we are in the middle of the section of my specialty, which are tiger moths.

Scene dissolves into another collection space with numerous cabinets, open drawers, and a diorama with a swarm of monarch butterflies.

RAB GREEN: Here at the Museum, we have about three and a half million specimens of moths and butterflies. And we have one of the world's best collections of butterflies of North America.

A bright glow suffuses the scene, and transitions to black and white archival images of a steam liner and the American Museum of Natural History.

[SHIP HORN, GULLS SQUAWKING]

RAB GREEN: Vladimir Nabokov came from Europe to the U.S. and within a year, he started volunteering actually at the Museum.

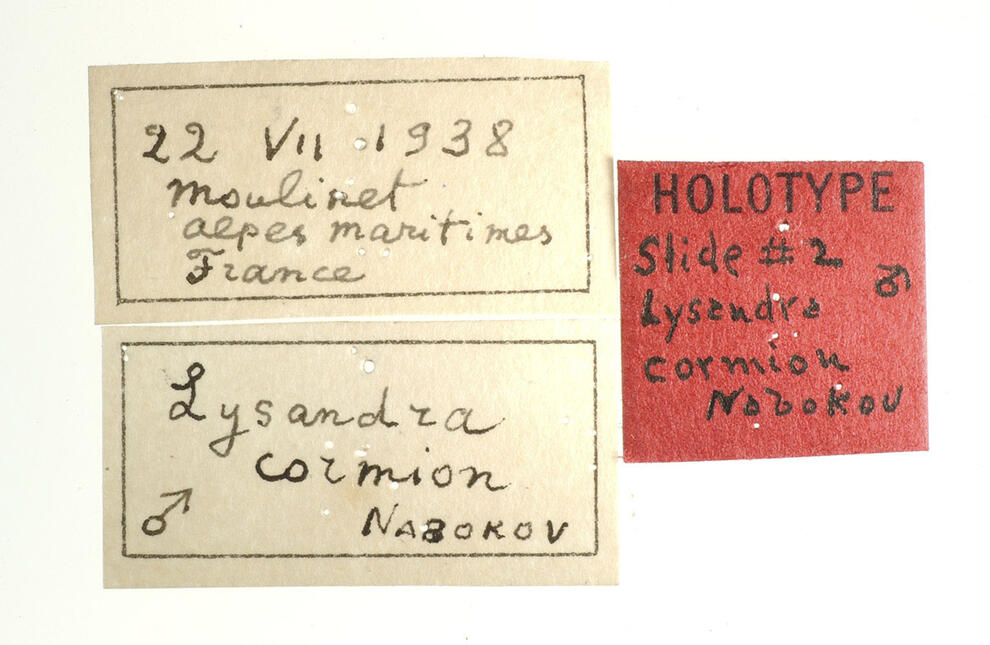

Butterflies—mostly blue and brown—expand across the screen. In the center is a blue butterfly with specimen labels reading "Lysandra cormion Nabokov," and "HOLOTYPE Slide #2." Thin white lines connect the different specimens.

RAB GREEN: Vladimir Nabokov's specialty was the blues, which is a group within the gossamer-winged butterflies. The blues are medium to small sized—kind of bluish-white and brown. There's lots of species, but they all seem to look alike. So, it's kind of a complicated group to work on.

Small blue butterflies fly toward the center of the screen. The white lines recede into the center butterfly, and the other specimens dissolve away.

[ROMANTIC 1940s MUSIC SWELLS]

RAB GREEN: In the summer of 1941,

Vintage postcard of a highway appears with the text, "May 26, 1941, Gettysburg, PA." Various butterfly specimens dissolve in.

RAB GREEN: when Nabokov set out on his trip with his family and a friend, he started in Pennsylvania,

Butterflies populate across the screen, following a white line unfolding across an abstract map landscape. More vintage postcards and town names appear—Luray, VA, Texarkana, AR, Grand Canyon AZ, Yosemite National Park, CA.

RAB GREEN: went down towards West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas... towards the West... Route 66... the Grand Canyon... And they ended in California.

Various letters from Nabokov to Museum staff appear. A blank postcard is front and center and writing in Nabokov's hand animates out: "I have done a good deal of collecting this season. Any, or all, specimens I have collected are at your disposal if they may be of use to the Museum. Yours very truly, V. Nabokov".

[PEN SCRATCHING ON PAPER]

RAB GREEN: After his trip, Nabokov decided to donate most of the specimens he brought back. So, here at the Museum, we have more than 350 specimens he collected on that road trip.

Camera is surrounded by packages and old cigar boxes in the collection room. Rab Green enters, opens a cigar box, and pulls out small glassine envelopes containing butterfly specimens.

RAB GREEN: Ever since I worked at the Museum, there was always this room filled from top to bottom with boxes. I started going through those, and I came across one box, which was labeled "Nabokov." I opened up and there were these specimens inside, and the envelopes the specimens were in had hand-written notes on them, with like a town name and the date.

Various specimen boxes and hand written labels appear—e.g., "Bristol Tenn. 29-V-41".

RAB GREEN: I thought it's maybe worth keeping them together for historic reasons.

[UPBEAT MUSIC WITH PLUCKING STRINGS]

Vintage postcards of the locations appear next to the butterfly specimens.

RAB GREEN: And I decided let's sort them by location instead of by species. I thought, "Oh, why don't I play around with Google Earth and georeference them."

The town names that are handwritten on the labels appear in white font.

RAB GREEN: That means when you have data, which are just written—like, let's say a town name on an envelope—

The printed town names scroll into random letters and numbers, finally landing on geographical coordinates—e.g., "34.90225000000001, -110.158186."

RAB GREEN: you find the geographical coordinates and plot that on the map.

Circle insets appear with shots of Google Earth locations referenced by the corresponding coordinates, and vintage home movie footage of roads and attractions in the 1940s. A white line animates out, connecting the locations.

RAB GREEN: You can have a visual picture of those locations. You can measure distances, how much they drove a day, so I could follow the track.

The scene dissolves to a blue-tinted vintage road map of the U.S. The word "GEOREFERENCING" appears at the top.

RAB GREEN: It's important to do georeferencing because it helps us understand things like species distribution,

Sections of the map are shaded to indicate the abstract idea of a particular species' distribution. Text reading "SPECIES DISTRIBUTION" appears.

RAB GREEN: migration patterns,

The shading on the map animates and moves from north to south to indicate migration. Text reading "MIGRATION PATTERN" appears.

RAB GREEN: environmental change.

Text reading "ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE" appears. The map changes color from a bluish tint to a warm red, then to a more neutral yellow. The text fades away. Circles expand across the map, indicating areas of species diversity, and blue butterflies fly around the map.

RAB GREEN: You can also predict that it would be worth conserving an area because it's very diverse with rare species.

The scene dissolves into a shot of Rab Green pinning butterfly specimens at her desk. Around the screen, there are colored circles, and circular insets showing details of the pinning process.

RAB GREEN: So, it's very important to know where a specimen was collected, and where it exactly comes from because if you see things which look the same, but they're geographically separated sometimes they are two different species. It's like opening a book and you expect something, and once you dive into the details you say, "Wow, that's a totally different story."

[GENTLE MUSIC, FEATURING A MUTED TRUMPET]

Production credits roll.

Vladimir Nabokov is best known for his literary masterpiece Lolita, but next to writing, his great passion was the study of moths and butterflies. Curatorial Assistant Suzanne Rab Green tells the story of the author’s first road trip across the U.S., where he drew inspiration and collected specimens along the way.

The Butterfly Trail

The highways and roadside motels of pre-interstate America provided the backdrop for literary giant Vladimir Nabokov's famous novel Lolita. But they were also prime collecting grounds for Nabokov’s great passion, lepidopterology—the study of moths and butterflies.

Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Nabokov was never a full-time entomologist, but he was an extremely knowledgeable amateur who published several scientific papers and described more than a dozen new butterflies.

Soon after moving to the U.S., Nabokov began volunteering in the Lepidoptera collections at the American Museum of Natural History. It was here that he met with early scientific encouragement and began to study the group that would later become his specialty: small Polyommatus butterflies known as blues. Recent genetic research has supported Nabokov’s 1945 hypothesis about the evolution of blues in the New World.

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

© AMNH

Nabokov took many road trips over his lifetime and drove thousands of miles across the United States, but his first cross-country adventure was in the summer of 1941. The writer donated many of the butterflies and moths collected on that trip to the Museum. Suzanne Rab Green geo-referenced and curated Nabokov’s 1941 collection, re-tracing his three-week cross-country road trip, providing a vivid record of a formative period for the great novelist.

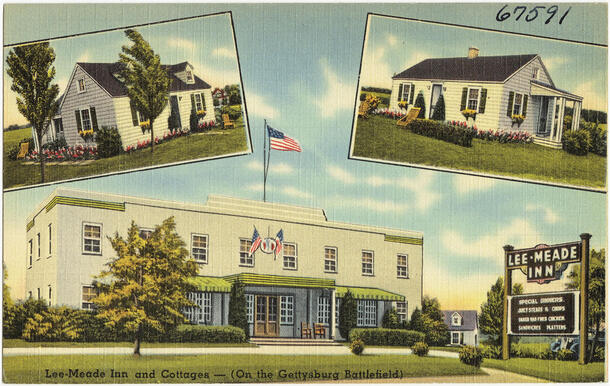

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Vladimir Nabokov's first cross-country trip of the U.S. began on May 26, 1941.

Driven by a student, the Nabokov family left New York City and would travel more than 3,000 miles in about three weeks. Their first night's stop was at the Lee-Meade Inn in Pennsylvania.

Credit: Boston Public Library

Nabokov collected these specimens in Gettysburg on May 27, 1941.

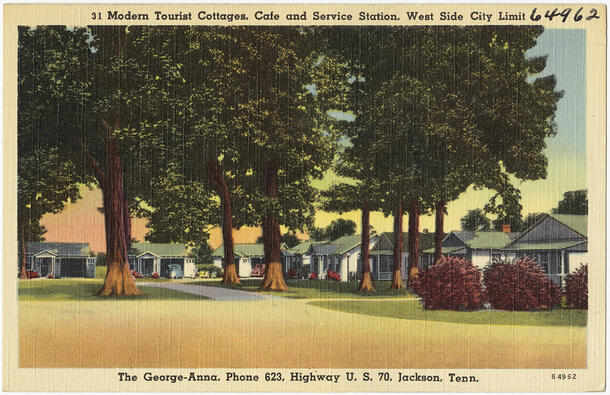

Jackson, Tennessee: Nabokov wrote to his mentor William Comstock at the Museum that most of his collecting "was done along the (more or less 'super') highways."

The motor courts he frequented along the way were often Nabokov's collecting grounds.

Credit: Boston Public Library

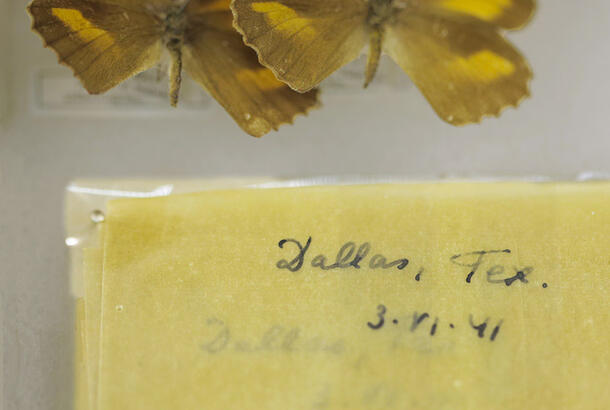

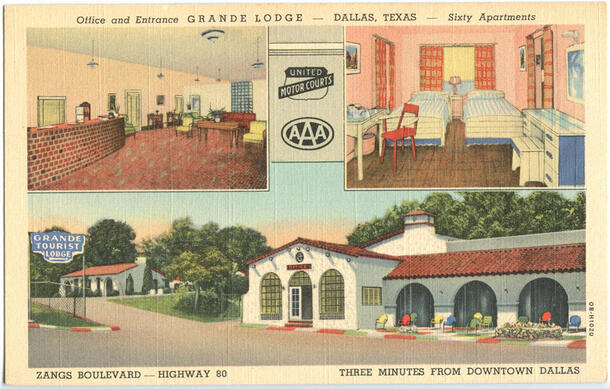

Dallas, Texas: Nabokov stored specimens in glassine envelopes, labeling each one carefully with location and date.

Entomologists often record the month of collection using roman numerals.

Butterfly specimens collected by Nabokov on June 3, 1941.

The night before, the Nabokov party had stopped at the Grande Tourist Lodge.

Credit: University of Texas Libraries

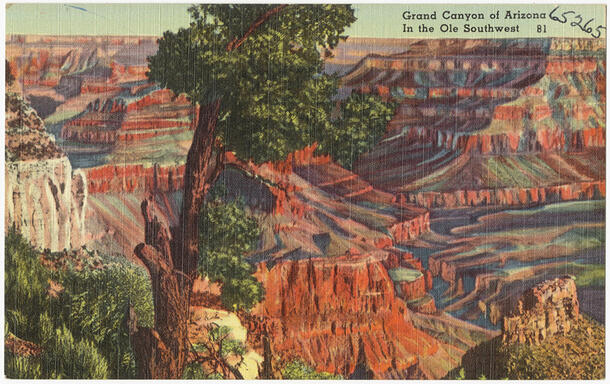

Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona: In the midst of his fast-paced road trip, Nabokov stayed for three days at the Grand Canyon.

Credit: Boston Public Library

There, despite stormy weather, he collected what he believed to be a new species, which he dubbed Neonympha dorothea in honor of their cross-country driver, Dorothy Leuthold. It's since been recognized as a subspecies—Cyllopsis pertepida dorothea.

Credit: S. Rab Green/© AMNH

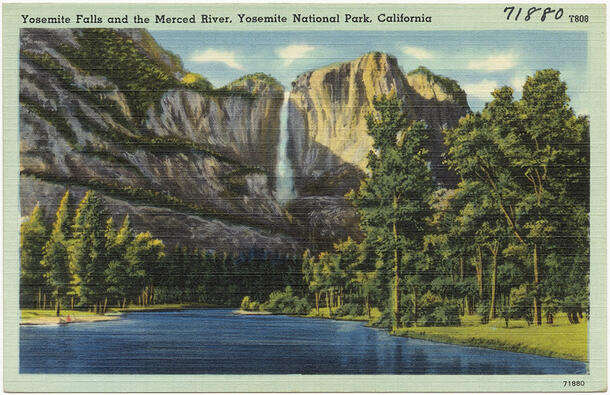

Yosemite National Park, California: The Nabokovs reached California in June. After several weeks at Stanford University, they visited Yosemite National Park, where the author couldn't help but gather more butterflies.

Credit: Boston Public Library

On September 11, Nabokov wrote to Comstock, saying, "I have done a good deal of collecting this season, and have had plenty of thrills and disappointments. The former consisted in meeting among their natural surroundings butterflies I had never seen before; the latter were the poor collecting grounds and bad weather."

In the same letter, he offered the specimens he had collected that summer to the Museum.