Shelf Life 07: The Language Detectives

PETER WHITELEY (Curator, Division of Anthropology): The Hopi account of their origins involves the migration in of multiple clans, from all directions. Most clans are associated with emergence from the world below. There’s a whole group of other clans, however, who migrated up from the South.

The Hopi language is- is one of a group of languages that we call Uto-Aztecan. Linguists have had their own ideas many ideas about where Uto-Aztecan languages arose.

But the exact nature of the relationships and what story it tells historically—that has been argued over ceaselessly for at least half a century.

[SHELF LIFE TITLE SEQUENCE]

WHITELEY: My name is Peter Whiteley and I’m the curator of North American ethnology.

WARD WHEELER (Curator-in-Charge, Science Computing Facility and Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology): My name is Ward Wheeler. I’m Curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Curator-In-Charge of computational sciences.

I’ve always done molecular systematics, but I always had a hankering to work on languages.

If we can think of words as sound sequences, each word is sort of like a gene.

WHITELEY: I became fascinated by the idea of this as a means for explaining evolution of languages.

The Uto-Aztecan languages stretch geographically from Idaho, all the way down to Panama, and they encompass a large number of different types of culture. All the way from very small-scale hunter-gatherer bands, like the Southern Paiute, to the Aztec society, which was a full-fledged state.

There have been multiple hypotheses about where Uto-Aztecan languages originate. There are some in recent years // that have suggested a southern origin.

That’s what we generally refer to as the farmer hypothesis. Languages originated in an area close to the origins of the domestication of maize, beans, and squash. And then radiated out from that.

Surely if it’s to be a knowledge that we would classify as scientific, there has to be a way of testing that.

WHEELER: Since I’ve been working so long with DNA sequences it was very easy for me to think about how we might generalize this to linguistic data.

So, instead of A-C-G-T, you have, you know, all the sounds people can make.

In the same way that we would look at variations in DNA sequences when we want to build a tree of organisms, we would look at variations in the sound sequences to build a tree of languages.

We took the existing algorithms that we had developed for DNA sequence analysis and were able to generalize them so that we could then use them for sound sequences—words.

In the same way that we need to use homologous genes when we compare organisms, so we want to compare apples to apples, we want to use homologous words, also. And the set of homologous words we use is called the Swadesh list.

WHITELEY: In the 1950s, Morris Swadesh, who was a very smart linguist determined on a set of 100 words that seemed to be most resistant to change by influence from other languages.

In English, this goes louse, two, water, ear, die, I, liver, eye, hand, hear, tree.

In Orayvi Hopi: [speaks Hopi]

So, we used the Swadesh List from 37 Uto-Aztecan languages. The words in the 100- word list came from missionary accounts, 19th century grammars and dictionaries, all the way on up to contemporary recording of languages that are still actively spoken.

All of the original sources had different ways of writing those languages. So, how do you compare them rigorously? You need to render them all into a single format—the International Phonetic Alphabet.

WHEELER: To understand the relationships among the Uto-Aztecan languages, we look to variations in the sound sequences in the words and from that, we can reconstruct evolutionary trees of the languages themselves.

We have to assign values to transformations between different sorts of sounds.

WHITELEY: The Hopi word for dog – [Hopi word]. In Shoshone— [Shoshone word]. And in another northern language, is something like [Numic word].

WHEELER: What is the cost of editing one word into another? Because that’s how you say one tree is better or worse than another tree.

You want to summarize all of those edits that transform all of those sequences into all those other sequences on a tree. And you add that up. That’s the cost of the tree.

So, when we have all the trees, which imply different sets of changes, we try to choose the lowest cost, the best interpretive framework that helps us reconstruct past events.

It’s among the most complex problems in computer science.

WHITELEY: The results of the analysis are confirming some perspectives that have existed for a long time, and challenging others.

We took this tree—the most likely relationships among the languages that we were working with—and then mapped it onto the landscape. It does tend to support the hypothesis for a southern origin.

WHEELER: We know things were happening first in the South. And then things were happening secondly in the North. And so, that meant there had to be a linguistic migration, moving north.

Plus, we developed a technique to analyze languages in a way that we feel is more objective and that’s a cool thing, too.

I became fascinated by the idea of [molecular systematics] as a means for explaining the evolution of languages.

-Peter Whiteley, Curator, Division of Anthropology

From A(ztec) to Yaqui

This month’s Shelf Life details how Museum curators Peter Whiteley, an anthropologist, and Ward Wheeler, a computational biologist, joined forces to trace the evolution of Native American languages by applying gene-sequencing methods to historical linguistics.

The researchers focused on the Uto-Aztecan family of languages, which have been spoken in Central and North America for millennia. Languages from this group were used in the bustling streets of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan—a city larger than 16th-century London—and spoken by nomadic groups tracking herds of bison across the plains of North America. Some Uto-Aztecan languages disappeared long ago while others, like Hopi, which Dr. Whiteley has studied for decades, are still spoken today.

Wikimedia Commons/Newberry Library, Chicago

For a glimpse at the variety of cultures in which these languages arose, Whiteley picked 12 objects from the Museum’s vast North American ethnological collection.

The journey begins in what is now Idaho, the northernmost point where Uto-Aztecan languages were historically spoken, and, some think, the farthest point to which this language family spread from its origins in the south—a hypothesis that’s consistent with Whiteley and Wheeler’s analysis.

This pair of beaded leather moccasins (below) from what is now Idaho represent the northernmost reach of the Uto-Aztecan languages. The style and craftsmanship are fairly typical of peoples from the Plateau culture area, who lived a nomadic lifestyle and hunted animals like deer and bison. They were likely made by members of either the Bannock nation, a Northern Paiute people, or the Northern Shoshone nation.

© AMNH

The medicine bag below (left) was crafted by the Ute people of the of the Great Basin region, which lies to the south of Idaho between the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains, encompassing parts of southern Utah, northern Arizona, southern Nevada, and southeastern California. After horses were introduced to the Americas by the Spanish and French, says Whiteley, the Utes became a formidable military force and dominated large swathes of the American Southwest.

A hide medicine bag from the Ute culture. Catalog Number 50/1276

A hide medicine bag from the Ute culture. Catalog Number 50/1276 © AMNH/Division of Anthropology

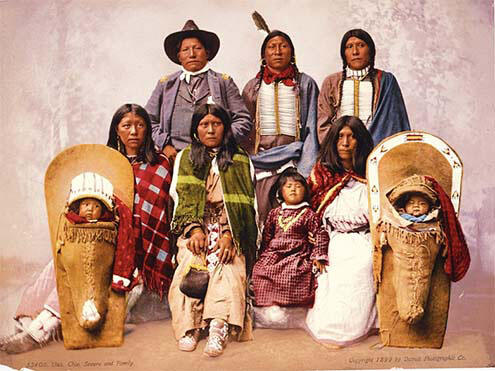

Ute Chief Sevara and his family. Photochrom print, 1885

Ute Chief Sevara and his family. Photochrom print, 1885 Library of Congress/96501843

The Great Basin was also home to the Southern Paiute, historically a nomadic culture of hunter-gatherers who lived in small groups. “Southern Paiute social organization would embrace maybe 40 or 50 people in a band,” says Whiteley. “To adapt to the environment, they lived in grass shelters that were very easy to transport.”

The war bonnet case pictured below would have held the headdress of a member of the Comanche people, a Plains group that followed bison herds throughout the year. Moving east across the Rocky Mountains in the early 18th century, the Comanches were known as the "Lords of the South Plains." By the 19th century, they had acquired many horses and wielded impressive political and military power.

© AMNH/Division of Anthropology

The noted Hopi artist Nampeyo crafted the pot pictured below in the late 19th or early 20th century. In contrast to some of their neighbors who lived by hunting and gathering, the Hopi have long been farmers who live in stone houses and stay on the same land for generations. Hopi agricultural practices go back “at least a millennium and a half, and maybe longer than that,” says Whiteley, who has conducted fieldwork among the Hopi since 1980.

© AMNH

This basket, collected in 1901, originated with the Cahuilla people in California. This group was traditionally semi-nomadic, hunting and fishing but also traveling throughout the region to gather the acorns that formed a staple of their diet.

© AMNH/Division of Anthropology

The effigy pot below, which depicts a person or figure, is from the Tohono O’odham, a Piman people once known as the Papago who practiced a mixed economy of foraging and agriculture, cultivating crops including maize, beans, squash, and melons in the Sonoran Desert. Pots like this one were particularly common at the prehistoric ruin of Paquimé (Casas Grandes) in Mexico. Whether the Tohono O’odham continued that tradition or independently developed their own is not known.

© AMNH/Division of Anthropology

This item originated with the Yaqui people, whose historic homeland is along today's border between the U.S. and Mexico. It would have been used in Matachines performances, spectacular masked dances that were adopted from Spanish colonists and are still performed in some villages today.

© AMNH

This seed necklace was crafted by the Tarahumara (also known as the Raramuri) people, who live near Chihuahua, Mexico. Unlike other Uto-Aztecan-speaking groups, the Tarahumara did not have much contact with the outside world until the middle of the 20th century. Today they maintain more aspects of their indigenous culture than other contemporary Uto-Aztecan groups.

© AMNH/Division of Anthropology

This beaded deer comes from the Museum’s large collection of Huichol artifacts. Native to the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains of central Mexico, the Huichol are an agricultural society perhaps best known for their “peyote hunts.” When collecting the fruits of the peyote cactus, which the Huichol consider a sacrament, the Huichol shoot the first cactus with an arrow, the same way they would hunt a deer.

© AMNH

To the west of the Huichol are the Cora, who crafted the rattle pictured here. The Cora are traditionally farmers and live near to what is now considered the origin of New World agriculture. At the time of first contact with the Spanish, the Cora occupied a large area on the western slope of Sierra Madre Occidental range. Their language may have been among the first of the Uto-Aztecan group, says Whiteley.

© AMNH

Finally, the second of the cultures that provides this linguistic family’s name: the Aztec, who spoke Nahuatl (as do their modern-day descendants, the Nahua). “If Southern Paiute is on one end of the continuum of cultural complexity, Aztec is on the opposite end,” says Whiteley, contrasting the tiny, nomadic bands native to the Great Basin with the complex city-states that formed Mesoamerica’s ancient empire.

This piece of Aztec art, called the Lienzo del Chalchihuitzan, dates back to around 1570 AD and illustrates the social status and inherited rights of the individual depicted at its center, through connections to ancestors and allies. Made in the decades following the conquest of Aztec civilization by the Spanish, Whiteley says, this artifact could represent an attempt by a lord—who likely commissioned the piece—to assert and defend his traditional privileges under a new authority.

“He’s laying out the terms of his chiefly privileges,” says Whiteley. “It’s kind of like his Magna Carta.”

© AMNH/Division of Anthropology

Farmers and hunters. City-dwellers and nomads. The 12 groups named above—and dozens more not represented here—are bound together by an ancient linguistic tradition that may help researchers learn more about how people and cultures spread throughout the Americas.